Savitribai Phule, born on 3 January 1831 at a village called Nayagaon in Satara district of Maharashtra, planted a little sapling on the barren land of women’s education and nursed it till it turned into a lush green tree. Education had been kept out of reach of the exploited and deprived Dalit tribals and women of the country for centuries. Her simplicity, selfless love, hardwork and commitment stood out as Savitribai, in partnership with her husband Jotiba Phule, secured the right to education for these communities. She demolished the conspiratorial monopoly of the upper castes on education.

In a country where awards are instituted in the name of the person who demanded Eklavya’s thumb as ‘gurudakshina’ (gift to the guru), where the slaying of a Shudra ascetic like Shambuk was a tradition, where the scriptures prescribed that hot mercury be poured into the ears of Shudras-Atishudras and women trying to acquire education, where the poet of the so-called Brahmanical society prescribed that ‘Dhol, Ganwar, Shudra, Pashu, Nari; Yeh Sab Taadan Ke Adhikari’ (Drum, rustics, Shudras, animals and women deserve to be beaten) – in such a country, it was nothing short of a miracle that a Shudra woman became the first non-missionary citizen to ignite the light of education for women and the Dalits. Unfortunately, in a country where ‘Jati Na Pucho Sadhu Kee, Puch Lijiye Gyan’ (Don’t ask the caste of a sadhu, ask how wise he is) is a maxim, education has come to be inextricably linked with one’s caste. If that is not so, why is Teacher’s Day celebrated in the name of Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan and not Savitribai Phule? Isn’t Savitribai’s contribution to the field of education momentous?

In a country where awards are instituted in the name of the person who demanded Eklavya’s thumb as ‘gurudakshina’ (gift to the guru), where the slaying of a Shudra ascetic like Shambuk was a tradition, where the scriptures prescribed that hot mercury be poured into the ears of Shudras-Atishudras and women trying to acquire education, where the poet of the so-called Brahmanical society prescribed that ‘Dhol, Ganwar, Shudra, Pashu, Nari; Yeh Sab Taadan Ke Adhikari’ (Drum, rustics, Shudras, animals and women deserve to be beaten) – in such a country, it was nothing short of a miracle that a Shudra woman became the first non-missionary citizen to ignite the light of education for women and the Dalits. Unfortunately, in a country where ‘Jati Na Pucho Sadhu Kee, Puch Lijiye Gyan’ (Don’t ask the caste of a sadhu, ask how wise he is) is a maxim, education has come to be inextricably linked with one’s caste. If that is not so, why is Teacher’s Day celebrated in the name of Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan and not Savitribai Phule? Isn’t Savitribai’s contribution to the field of education momentous?

Savitribai Phule was not only the first non-missionary Indian woman teacher and headmistress but also a great social reformer and an enlightened poet and thinker. She has become a source of inspiration to many.

In Savitribai’s time, religious superstitions, bigotry and untouchability ruled the roost. Dalits and women were subjected to all sorts of mental and physical torture: Child marriage, sati, female infanticide and inhuman treatment of widows were common. Young women were married off to much older men and polygamy was the order of the day. Against this backdrop, Savitribai and Jotiba standing up to the unjust society was akin to stirring a cesspool of stagnant, stinking water.

Education

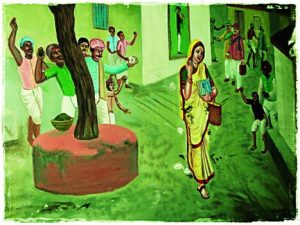

Savitribai Phule kicked open the doors of education, which were closed for Shudras-Atishudras and women for hundreds of years. The Sanatanis of Pune did not take kindly to the news of these doors being thrown open. They mounted murderous assaults on Savitri and Jotiba Phule. To extinguish the lamp of education lit by the Phule couple, they provoked Jotiba’s father Govindrao to turn the couple out of his home. They hurled cow dung and stones at Savitribai whenever she left her home to teach the girls. Upper caste goons stopped her on the way and abused her. She was threatened with death. Many attempts were made to close the school for girls. The Sanatanis wanted Savitribai to confine herself to her home. One goon followed Savitribai daily and taunted and harassed her. One day, he crossed all limits – he blocked her way and tried to hit her. Savitribai courageously retaliated and slapped him hard thrice. The man was so embarrassed that he never again came in her way. And so Jotiba and Savitribai continued with their work.

Savitribai Phule kicked open the doors of education, which were closed for Shudras-Atishudras and women for hundreds of years. The Sanatanis of Pune did not take kindly to the news of these doors being thrown open. They mounted murderous assaults on Savitri and Jotiba Phule. To extinguish the lamp of education lit by the Phule couple, they provoked Jotiba’s father Govindrao to turn the couple out of his home. They hurled cow dung and stones at Savitribai whenever she left her home to teach the girls. Upper caste goons stopped her on the way and abused her. She was threatened with death. Many attempts were made to close the school for girls. The Sanatanis wanted Savitribai to confine herself to her home. One goon followed Savitribai daily and taunted and harassed her. One day, he crossed all limits – he blocked her way and tried to hit her. Savitribai courageously retaliated and slapped him hard thrice. The man was so embarrassed that he never again came in her way. And so Jotiba and Savitribai continued with their work.

Under the Brahmin Peshwa rulers untouchability had taken on the most cruel, inhuman forms in Pune and the surrounding areas. By choosing to open their schools in Pune, the Phules were sending out a clear message that they were striking at the very root of Brahmanism.

That in such a casteist context a Shudra couple like the Phules were able to start and sustain several schools for girls of all castes including from the untouchable communities was nothing short of a social revolution. This kind of sweeping change had no precedent in India’s history. Despite their seminal contribution to social change, the arrogant upper castes have not given them their due place in our history. It is a matter of great satisfaction and joy that the Dalit-OBCs are rewriting history and making the world aware of the contribution of the Phules. The Phules’ selfless mission has become the guiding light of many a member of the deprived classes. Inspired by them, schools and colleges are being established in their names, thus extending financial, social and emotional support to the students of these classes.

Six girls took admission in the first school opened at Bhide Wada, Budhwar Peth, in Pune in 1848. They were aged between four and six. Their names were Annapurna Joshi, Sumati Mokashi, Durga Deshmukh, Madhavi Thatte, Sonu Pawar and Jani Kardile. While Savitribai started classes for these six girls, she also began going from door to door, requesting parents to educate their daughters. Her campaign was so effective that the number of students in the school grew and soon it became necessary to appoint one more teacher. Vishnu Pant Thatte agreed to teach in the school for free. In 1849, Savitribai established an adult education centre in the house of Usman Sheikh, again in Pune, for Muslim women and children. Soon she started new schools in Pune, Satara and Ahmednagar.

India’s first feminist

Savitribai’s contributions were not only limited to the field of education. In 1852, she established the Mahila Seva Mandal (Women’s Service Organization) with the objective of improving the lot of Indian women. She was thus the first leader of the Indian feminist movement. The Mandal strongly opposed various social practices that were detrimental to the wellbeing of the women. One such practice was the tonsuring of widows among the Hindus. To put an end to this, she launched a campaign urging the barbers not to cut the hair of widows. A large number of barbers took an oath to stop doing so. There are few, if any, instances in the history of the world of men in large numbers enthusiastically joining a movement against the physical or mental torture of women, that too at financial loss to themselves. Many organisations of barbers made common cause with Savitribai’s Mahila Seva Mandal. She and her comrades in the Mandal launched several such movements with great success.

Our history, religious scriptures and social reform movements show that women were valued even less than animals. If a woman became a widow, the men in her family, including brothers-in-law, father-in-law and others, exploited her physically. Sometimes, such women used to become pregnant. Their tormentors took no time in disowning them and to save themselves from ignominy, they were left with only two options: either to commit suicide or to kill their illegitimate child. To ensure that women stopped taking either of the two paths, Savitribai established the country’s first Bal Hatya Pratibhandhak Griha (home for infanticide prevention) and also a home for destitute women.

She persuaded a Brahmin widow Kashibai – who had become pregnant – not to commit suicide and took the woman to her own home where, in due course, she delivered a baby boy. Savitribai adopted the boy and named him Yashwant. She educated him, and he went on to become a doctor. Then he married a woman of another caste in what was the first recorded inter-caste wedding in Maharashtra.

She persuaded a Brahmin widow Kashibai – who had become pregnant – not to commit suicide and took the woman to her own home where, in due course, she delivered a baby boy. Savitribai adopted the boy and named him Yashwant. She educated him, and he went on to become a doctor. Then he married a woman of another caste in what was the first recorded inter-caste wedding in Maharashtra.

Savitribai and Jotiba Phule practised what they preached. In fact, they started the process of social reform from their own home. Savitribai organized and conducted inter-caste marriages all her life with the objective of establishing a casteless and classless society. For almost 48 years, she worked unceasingly for the Dalits and the exploited and suffering women, inspiring them to lead a life of dignity and self-respect.

Poet of liberation

India’s first woman teacher and the harbinger of social revolution, Savitribai Phule was also a famous poetess. In one of her well-known poems she urges all to study, break free from the bondages of caste and throw away Brahmin scriptures.

Go, Get Education

Be self-reliant, be industrious

Work-gather wisdom and riches.

All gets lost without knowledge

We become animals without wisdom.

Sit idle no more, go, get education

End misery of the oppressed and forsaken.

You’ve got a golden chance to learn

So learn and break the chains of caste.

Throw away the Brahmin’s scriptures fast.

As a thinker, Savitribai argued that social inequality was not the creation of God; it was the selfish humans themselves who pronounced some greater than others. Caste, she said, had been created by some to secure their future and to lead a life of luxury. When Savitribai supported inter-caste marriages, her brother wrote to her: “You and your husband have been boycotted. The work you do for Mahars and the Mangs is corrupting your family. That is why I tell you to do what the Bhatt says and work within the caste system.” She hit back at her brother’s conservative views. “My brother, you have a weak brain and it has been further weakened because of the teachings of the Bhatts,” she wrote.

In another letter, she gives a heart-rending description of the famine of 1877. In those difficult times, Savitribai and Jotiba Phule not only started Anna Satra but also appealed to the people to donate foodgrains for those affected by the famine.

After the death of Jotiba Phule in 1890, Savitribai continued to serve the needy. In 1897, when plague assumed epidemical proportions in Maharashtra, Savitribai attended to the patients without caring for her own safety. She contracted plague while trying to save a Dalit child, and passed away on 10 March 1897 at the hospital run by her son Yashwant.

Savitribai Phule has become immortal. For the last couple of years, the depressed and exploited classes, for whose rights she struggled all her life, have been observing her birth anniversary as Indian Education Day and her death anniversary as Indian Women’s Day.

Published in the January 2014 issue of the FORWARD Press magazine

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of the Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) community’s literature, culture, society and culture. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +919968527911, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)