While most of the pre-poll surveys and exit polls had indicated a victory for the Aam Aadmi Party and some even a big victory for the party, none of them had predicted such a massive sweep as the recent Delhi Assembly election turned out to be for AAP. The party went on to win 67 of the 70 assembly seats while the BJP managed to win only the remaining three (Rohini, Mustafabad and Vishwas Nagar). This is not merely a victory for a party – it reflects massive faith in a person, Arvind Kejriwal, who led a party and contested against the most powerful party at this moment both in terms of electoral support and resources. With a small number of leaders and a relatively small amount of money, AAP could register such a convincing victory.

Hardly has there been an occasion in Indian politics when a party registered a victory as massive as AAP’s. Only Sikkim comes to mind, where the ruling Sikkim Democratic Front (SDF) managed to win all the 32 seats in the assembly, twice, in 1989 and 2009, and only one less in the 2004 assembly elections. There are a few other big victories of regional parties in different states, but they are nothing compared to the victory of AAP in Delhi where it not only managed to win all but three seats, but polled 54.3 per cent of the votes. There have been few occasions when the winner has polled more than 50 percent votes in a triangular contest. The country has witnessed electoral waves in the past, like the 1977 Janata Wave, the 1984 Rajiv Gandhi wave, or the 1989 V.P. Singh wave, and this election certainly goes into the history of Indian elections as another wave, namely the “Kejriwal wave”, or something even more.

Hardly has there been an occasion in Indian politics when a party registered a victory as massive as AAP’s. Only Sikkim comes to mind, where the ruling Sikkim Democratic Front (SDF) managed to win all the 32 seats in the assembly, twice, in 1989 and 2009, and only one less in the 2004 assembly elections. There are a few other big victories of regional parties in different states, but they are nothing compared to the victory of AAP in Delhi where it not only managed to win all but three seats, but polled 54.3 per cent of the votes. There have been few occasions when the winner has polled more than 50 percent votes in a triangular contest. The country has witnessed electoral waves in the past, like the 1977 Janata Wave, the 1984 Rajiv Gandhi wave, or the 1989 V.P. Singh wave, and this election certainly goes into the history of Indian elections as another wave, namely the “Kejriwal wave”, or something even more.

After its massive victory in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, BJP continued its victory march in all the state assembly elections held during the last few months, and to many, the BJP seemed invincible – until the victory rath of BJP was not only halted by Kejriwal, but was actually completely wrecked. For BJP, it is not merely a defeat, but maybe the most humiliating defeat, with only three seats and 32.7 per cent of the votes. One could hardly believe that the party which led in 60 of the 70 assembly segments barely 8 months ago would be routed in these elections. It is important to understand what really happened during last eight months which completely changed the electoral landscape of Delhi. How could a party which led its nearest rival by more than 13 per cent votes fall so far behind in barely a few months’ time?

Table 1: Delhi’s Party Performance: 2013-15

| Party | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seats | Vote % | Seats* | Vote % | Seats | Vote % | |

| AAP | 28 | 29.5 | 10 | 32.9 | 67 | 54.3 |

| BJP+ | 33 | 34.0 | 60 | 46.4 | 3 | 32.7 |

| Congress | 8 | 24.6 | 0 | 15.2 | 0 | 9.7 |

*Assembly segment leads

Positive vote for AAP, not negative vote for BJP

This is more a positive vote for AAP rather than a negative vote for BJP or Modi. Had this been only a negative vote for BJP, the victory wouldn’t have been so massive. While almost all parties promised to provide electricity and water supply at reduced rates, and every party promised a more secure environment for women, the entire election turned into a referendum on AAP’s chief ministerial candidate Arvind Kejriwal, and AAP benefited from this phenomenon. Kejriwal was much more popular than any other leader, and even the votes polled by AAP are a clear indication that some sections of voters voted for AAP only due to Arvind Kejriwal. Though large numbers of voters seemed to be sharply polarized in favour of different parties well in advance, a lot of them changed their mind at the last minute and voted for AAP.

The projection of Kiran Bedi as BJP’s chief ministerial candidate to counter the popularity of Arvind Kejriwal seemed to have backfired. She failed to muster additional support for the party and even lost her own election from the “safe” Krishna Nagar constituency. Sensing that the Kiran Bedi card may not work, BJP parachuted a large number of its MPs, cabinet ministers and even neighbouring states’ chief ministers to campaign for the party. The party could not assess if this might help its candidates and hence resorted to a very aggressive negative campaign, with personal attacks against Arvind Kejriwal through advertisements in newspapers. This didn’t go down well with a large section of Delhi voters, damaging BJP’s prospects in these elections. On the other hand, in spite of the aggressive negative campaign against its leader, AAP stuck to a very positive campaign, focusing on what they would like to give to the people of Delhi if voted to power. While the party may find it difficult to fulfil some of its promises, at least the people showed faith in those promises, resulting in such a massive mandate.Dalit

Delhi’s politics is always discussed in terms of regions like old Delhi, trans-Yamuna areas, south Delhi or central Delhi, as the nature of electoral contest slightly differs from region to region given the different social compositions of voters. But this victory seems to have wiped out all the differences. The AAP swept the elections in all the regions and the entire Delhi was painted AAP green. Usually, there is also the talk of the Jat vote or the Punjabi vote, the Muslim vote or the Dalit vote. Except for the voters belonging to the Brahmin, Vaishya/Baniya and the Jat communities, all other communities voted for AAP in big numbers. Even the Punjabi Khatris who had favoured the BJP in the past elections voted for AAP in sizeable numbers (See Table 2).

Table 2: Vote by Caste and Community

| Caste/Community | INC | BJP | AAP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brahmin | 8 | 49 | 41 |

| Punjabi Khatri | 13 | 33 | 52 |

| Rajput | 9 | 44 | 44 |

| Vaishya/Jain | 7 | 60 | 31 |

| Other Upper | 7 | 39 | 48 |

| Jat | 5 | 59 | 31 |

| Gujjar/Yadav | 7 | 35 | 53 |

| Other OBCs | 9 | 29 | 60 |

| Dalit | 6 | 20 | 68 |

| Muslim | 20 | 2 | 77 |

| Sikh | 8 | 34 | 57 |

The middle class had been unhappy about Kejriwal’s quitting the government after just 49 days in power. He was labelled as bhagoda, largely by the middle-class voters. But as the results indicate, a large number of middle class votes went to AAP. Predictably, the vote share of AAP was much higher among the poor; it established a lead of more than 40 per cent over BJP among this class of voters. A large number of lower- and middle-class voters also voted for AAP. It was only among the upper-class voters that BJP could pose a challenge for AAP, though the gap between the BJP and AAP narrowed to just 4 percentage points. The Congress, whose vote share dropped to below ten per cent (9.7 percent, to be precise), performed poorly across these groups of voters (See Table 3).

Table 3: Vote by Economic Class

| Economic class | INC | BJP+ | AAP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | 9 | 22 | 66 |

| Lower | 10 | 29 | 57 |

| Middle | 13 | 35 | 51 |

| Upper Middle/Rich | 6 | 43 | 47 |

The results of the latest Delhi Assembly elections further confirm the trends I had analyzed in my 2013 book, Changing Electoral Politics in Delhi: From Caste to Class. Based on a first-hand survey data of a cross section of voters and an analysis of the previous four assembly election results, it became obvious that increasingly caste and regional identity might still be necessary but are no longer sufficient for electoral victory in cosmopolitan Delhi.

Poll-arization favoured AAP

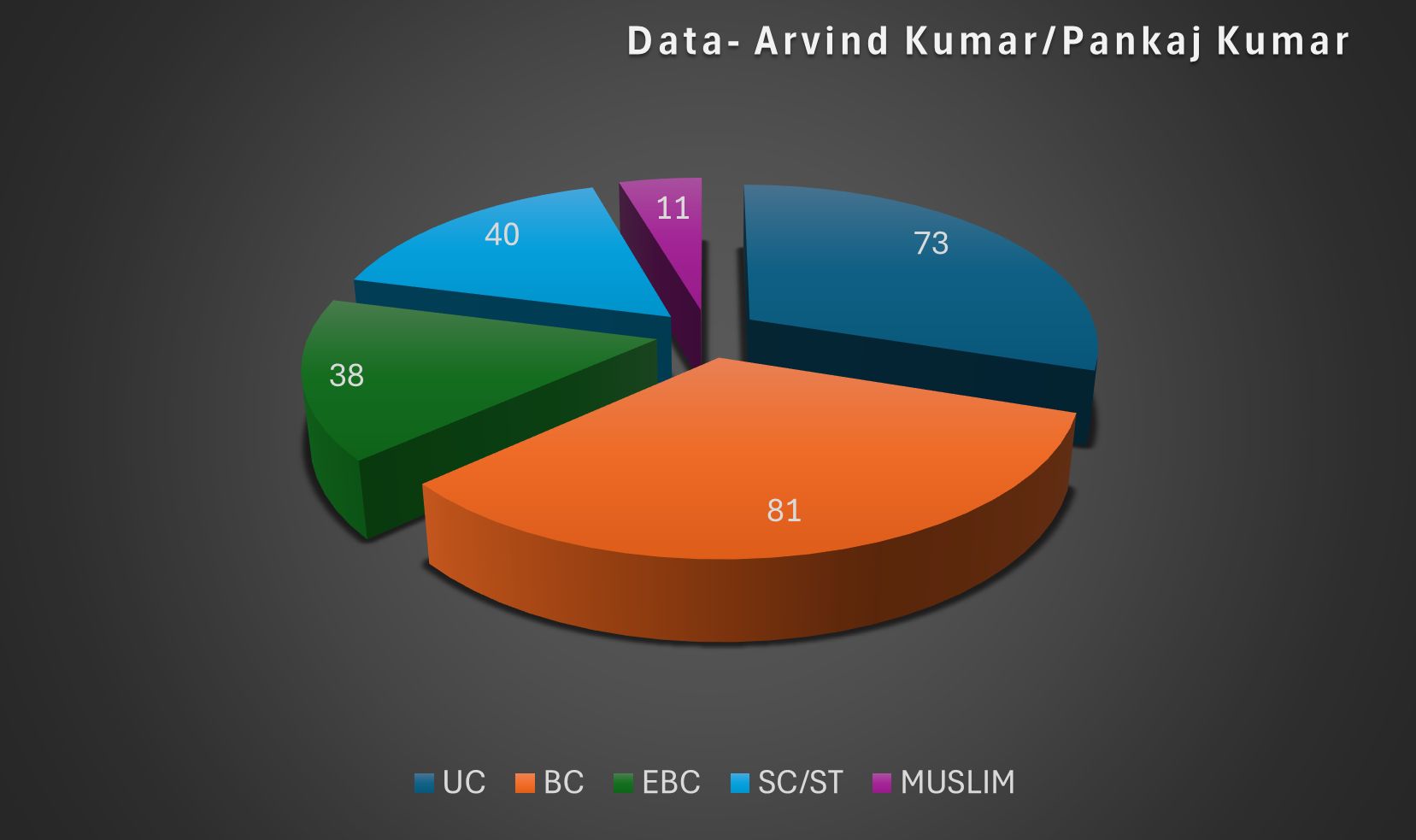

What seemed to have contributed to the AAP victory is a very sharp polarization of the minorities, mainly the Muslims, who constitute 11 per cent of Delhi’s voters. Their concentration in 8-9 assembly constituencies swung the elections in these seats in AAP’s favour. The Muslim vote, which remained divided between the Congress and AAP in the 2013 assembly election, shifted in favour of AAP in a big way; more than three fourths of the Muslim voters (77 per cent) voted for AAP in these elections, giving the party a decisive lead. Had 2013 assembly elections witnessed a similar shift, this election may not have been necessary for AAP. The shift of the Muslim vote towards AAP had happened during the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, but the enormous popularity of BJP among various other sections, including Punjabi Khatris, Jats and OBCs, negated the effect of the Muslim vote for AAP. As in many other states, the Congress lost its Muslim support in Delhi. Though a sizeable proportion of Sikh voters voted for AAP, their vote remained largely divided between the two main parties.

Among the various Dalit castes close to 7 out of ten (68 percent) voters voted for AAP. This, to a great extent explains AAP’s victory in all the seats reserved for Dalits. The 2014 Lok Sabha election, however, had witnessed a significant shift of Dalit votes in favour of BJP in Delhi as in many other states.

The Punjabis also seemed to have switched allegiance to AAP. The land acquisition ordinance may have cost BJP as Jats and Gujjars with land in UP or Haryana, who have a sizeable presence in many constituencies in outer Delhi, seemed to have voted for AAP. This gave AAP the edge over BJP in many Jat- and Gujjar-dominated constituencies.

Another major factor contributing to AAP’s victory was the support it enjoyed among the youth of the city. The party’s vote share among the youngest age group (up to 22 years) and those aged 26-35 years has been much higher than its overall vote share. The gap between BJP and AAP falls from more than 37 percentage points among the young voters (18-22 years) to less than 10 points among the older voters (See Table 4).

Table 4: Vote by Age Group

| Age group | INC | BJP | AAP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18-22 years | 10 | 26 | 63 |

| 23-25 years | 11 | 36 | 50 |

| 26-35 years | 6 | 31 | 60 |

| 36- 45 years | 7 | 34 | 54 |

| 46- 55 years | 11 | 34 | 50 |

| 56 and above | 16 | 36 | 45 |

Do we see this defeat as a personal defeat of Narendra Modi or of BJP? I would not treat this as a referendum on the performance of the Modi-led central government, and the voters who have voted for AAP seemed satisfied with the work of the central government. This is neither a reflection of the declining popularity of the central government or of Narendra Modi nor a rejection of the work done by the central government so far. But because BJP had made this election a prestige issue – with the prime minister putting in all his energy in the campaign, more than 200 MPs and many chief ministers and central government ministers campaigning for BJP – this defeat should mean more than a routine defeat. This indicates a complete rejection of the kind of politics that BJP has been pursuing during the last few months, especially during the election campaign – the politics of arrogance, negativity, etc.

Symbolically, this defeat of BJP in the capital will boost the morale of the leaders of opposition parties – Trinamool Congress workers celebrated BJP’s defeat and AAP’s victory on the streets of Calcutta – but I doubt if this will help in consolidating the existing electoral base of regional parties in the states which are going to the polls in the next year or so. I don’t see how this will help mobilize additional electoral support for RJD or JD-U in Bihar, for the Samajwadi Party or BSP in UP. The parties need to strategize, keeping in mind the emerging issues in their respective states. If they think this victory will have a strong spillover effect and if they think there is a national wave against Modi or the BJP, they are mistaken. Like AAP and Kejriwal, they will need to connect with the people if they are hoping to put up a strong contest against the BJP.

Published in the March 2015 issue of the Forward Press magazine

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of the Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) community’s literature, culture, society and culture. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +919968527911, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)