Ever since the emergence of Pasmanda movement on the large political scene in the 1990s, traditional minority politics has come in for sharp criticism from the new cultural imaginary. Influenced by Mandal politics (1990s), the Pasmanda movement has not only questioned the hegemony of ashraf (upper-caste) Muslims but also succeeded in rewriting history and replacing the symbols and idioms of “elite” minority politics.

Ever since the emergence of Pasmanda movement on the large political scene in the 1990s, traditional minority politics has come in for sharp criticism from the new cultural imaginary. Influenced by Mandal politics (1990s), the Pasmanda movement has not only questioned the hegemony of ashraf (upper-caste) Muslims but also succeeded in rewriting history and replacing the symbols and idioms of “elite” minority politics.

Pasmanda, a Persian term, refers to those who have “fallen behind”, according to Masawat ki Jung (2001), a book that is often cited by the Pasmanda leader and JD (U) MP Ali Anwar. Examples of some well-known Pasmanda castes are Lalbegi, Halalkhor, Monchi, Pasi, Bhant, Bhatiyara, Pamriya, Nat, Bakkho, Dafali, Nalband, Dhobi, Sai, Rangrez, Chik, Mirshikar and Darzi. Simply put, Pasmanda Muslims are Backwards (Shudra) and Dalits (Ati-shudra) who embraced Islam centuries ago to free themselves from caste atrocities. But the change of religion did not liberate them from caste discrimination and material deprivation. Despite the fact that Islam underscores equality and brotherhood, there are often media reports of Dalit Muslims being denied entry to mosques and graveyards by ashraf Muslims. Besides, inter-caste marriages in Muslim society are also not common.

Thus the Pasmanda leaders lay more emphasis on their Dalit and backward identity than their Muslim identity, questioning the idea of Muslims being a “monolithic” community. In recognition of the caste discrimination among Muslims, Pasmanda politics aims at arriving at a broader “Bahujan unity” of Dalits and Backwards across religions.

Pasmanda intellectual Khalid Anis Ansari has divided the Pasmanda movement into two phases. While the second phase was the byproduct of Mandal politics (1990s), the first phase goes back to the era of the Momin Conference in Bihar. The Momin Conference (1930s and 1940s) was shaped by nationalist movements and the politics of the Congress.

Founded in Kolkata by Bihari Muslims, the Momin Conference rejected both Hindu and Muslim nationalisms. However, the organization could not remain active after Independence when its top leader Qaiyum Ansari (1905-1974) became a minister in the Congress-led Bihar government.

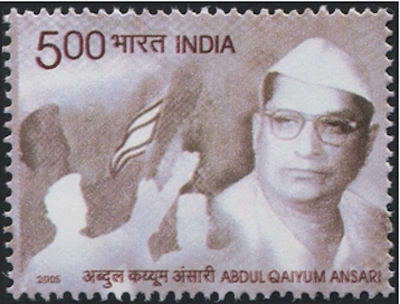

Qaiyum Ansari is considered to be one of the most popular icons of the Pasmanda movement. The Indian government has even issued a postal stamp in his name. Ansari emerged on the wider political scene in Bihar in the early 1940s, writes historian Mohammad Sajjad in Muslim Politics in Bihar (2014).

Qaiyum Ansari was also the president of the Bihar Provincial Jamiat-ul-Momineen. He joined the freedom struggle during the Khilafat Movement when he came in contact with the Ali Brothers in Sasaram, Bihar. His “assertive” politics in the 1930s and the 1940s opposed the Muslim League and the two-nation theory. After Independence, he became a minister in various Congress state governments (1946-52, 1955-57 and 1962-67) and later the president of the party’s Bihar Pradesh Committee, a member of Congress Working Committee and a Rajya Sabha member (1970-72).

Decades after the death of Ansari, the second phase of Pasmanda movement resumed under the influence of politics of social justice in Bihar. The first major Pasmanda organization was All India Backward Muslim Morcha, founded in 1994 by Dr Eijaz Ali, and later Pasmanda Muslim Mahaz, founded by Ali Anwar in 1998.

While the Pasmanda movement was close to the Congress party in the first phase, it saw the parties of social justice, such as the Janata Dal, the SP, the BSP, the RJD and the JD(U), as its natural allies in the second phase. The reason for this unity between the oppressed from the Hindu and Muslim folds is based on their “shared suffering”, “dard ka rishta”, common “experience”, “occupation” and “humiliation” inflicted on them by members of the upper castes.

The Pasmanda movement’s slogan “pichhra pichhra ek saman Hindu ho ya Musalman” (Dalits and backwards are the same whether they are Hindus or Muslims) brilliantly encapsulates this point.

This Bahujan solidarity among Dalits and Backwards across religions owes a lot to the political ideology of the BSP founder Kanshi Ram, who invented the concept of Bahujan and created a new political bloc in Indian politics, comprising Dalits, Backwards, and minorities. Traditional politics said Dalits and Muslims were minorities, but Kanshi Ram argued that the exploiting upper castes were a minority while the oppressed were the majority (Bahujan).

A change in political equation and identity requires reinterpretation of history too. While traditional Muslim scholarship had often ignored the question of caste, the Pasmanda Muslim intellectuals give it primacy. For example, Masood Alam Falahi [Hindustan Mein Zaat-Paat Aur Musalman (2007)] argues that lower-caste Muslims have been discriminated against and denied access to power since the medieval period. Mughal emperors Aurangzeb (1618-1707) and Bahadur Shah Zafar (1775-1862) began to be seen as casteist. Even Muslim icons of modern India such as Sir Syed Ahmed Khan (1817-1898), the founder of Aligarh Muslim University, used, it was pointed out, derogatory language against lower-caste Muslims (badzat jolha) and was a protector of upper-caste interests.

By demolishing the ashraf icons, the Pasmanda Muslims constructed new icons, which belonged to the Kabir-Phule-Ambedkar tradition. While they adopted Babasaheb Ambedkar as an icon because of his struggle against the caste system, they put OBC leader Karpoori Thakur right up there with Ambedkar. When he served as Bihar’s chief minister, Thakur gave 26 per cent reservation to the backward castes in which many Dalit Muslim castes were also included.

Besides them, the Pasmanda movement has also adopted new icons from lower-caste Muslim groups. They are Veer Abdul Hamid (1933-1965), who was conferred Paramveer Chakra for his heroic fight during the 1965 Pakistan War; Bismillah Khan (1913-2006), renowned shehnai player and the 2001 Bharat Ratna awardee; Qaiyum Ansari; and Maulana Atikurraham Aarvi, who was a student of Darul Uloom Deoband and a nationalist freedom fighter.

By adopting these icons, Pasmanda Muslims have challenged the hegemony of the upper castes in the sphere of culture and civil society. This invention of a new cultural imaginary is a welcome development in the intensifying Dalitization of public culture.

Published in the October 2015 issue of the FORWARD Press magazine