Mahatma Phule (1827-1890) is hailed as the father of the social revolution in India but not many know that he is the original architect of India’s gender revolution as well. The seeds of his feminist sensibilities were sown in his childhood and adolescence and then there was Savitribai, with whom he lived and worked for 50 years to contribute immensely to the women’s reform movement of 19th-century Maharashtra. The Phule couple were partners in every sense of the term. It is impossible to divorce Jotirao’s theory from practice, his work from that of Savitribai’s, their work from their life.

Early influences

Jotirao Govindrao Phule belonged to the Mali caste whose members were traditionally gardeners and were considered “low caste” or Shudras in the brahmanical (Hindu) caste hierarchy. This community was not expected to receive education but be subservient to the “higher castes”. Despite having the odds stacked against him, Jotirao was exposed to English education, thanks to his enlightened aunt Sagunabai, a child widow, who came to Pune to care for him when his own mother died in his infancy.

To earn a living, she took up a job as a domestic help and babysitter in the house of a dedicated missionary, Mr John, who ran an orphanage. Jotirao would accompany his aunt to work every day. She picked up some English on her job. She also absorbed some of the Christian values of equality, liberty, fraternity that were part and parcel of the many discussions at her workplace and later infused these values into Jotirao. It was on her insistence that he was put in a Scottish Mission school. This exposed Jotirao to Western reformist literature. A significant input came from the criticism of establishment religion in the French Enlightenment and the political thought of France and England in the post-Revolution decades. Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man and Age of Reason, with his emphasis on the natural rights of individuals and the need to subject traditional institutions, including religion, to free discussion and criticism, made a deep impact on him.

Significantly, Sagunabai had started a school for the “untouchables” in 1846 but it had to be closed down in six months for lack of support. Thus the Phules already had a role model and a precedent in Sagunabai and her work.

The young Jotirao had diverse influences acting upon him, as attested by Jotirao himself at the end of his seminal essay, Cultivator’s Whipcord:

I first remember with gratitude my childhood Mussalman neighbours and playmates in whose company I began to have true thoughts about the falsities of the selfish Hindu religion and its false ideas of caste distinctions, etc. Second, I express my gratitude to the Scottish Mission in Pune and the government institution – through whom I acquired some education and understanding of what a human being’s rights are … Then I thank the independent rule of the British government because of which I could express my views without fear … (Deshpande, 2002, p 183)

Along with these, the thoughts and writings of Gautam Buddha, Kabir, Tukaram and Ashwaghosh (author of the book Vajrasuchi), as well as the teachings of Jesus Christ and Mohammad, had a great influence on Jotirao.

The historical context

The turn of the 19th century saw a spurt of social reforms ushered in by men, beginning in Bengal and spreading to other parts of India, including Maharashtra. The British had taken over Poona in 1818 marking the end of the Peshwa rule of the Brahmins. An important aspect of the reforms was the upliftment of women. The abysmally low status of Indian women and the cruel practices like sati, enforced widowhood, infant marriage and purdah grabbed their attention.

Around the time that young Jotirao was growing up, the social reform movement was gathering tempo. The reform movement was largely an upper-caste phenomenon and the subject of their concern, however limited, was the upper-caste woman. Nevertheless, it had the potential to go beyond its immediate class\caste interests and it did, ushering in the entry of non-Brahmin reformers led by Jotirao Phule.

Jotirao began to apply the principles of human rights discourse to the caste- and gender-stratified Hindu, brahmanical social order. He realized that education was key to the liberation of what he termed as the Shudras, ati-Shudras and women, as these sections had been deliberately and forcibly kept away from education by the brahmanical caste order.

Phules’ gender reforms

The first gender-sensitive act of Jotirao was to encourage his young wife Savitri to read and write. He taught her and his aunt Sagunabai while he was still studying in the missionary school. Savitri was a bright and eager student, and went on to acquire a teacher’s training certificate.

The Phules started their first school for girls on 15 May 1848 at Bhidewada, Poona. Savitribai was its headmistress. The school brought together girls of all castes under one roof. The first batch had 25 girls. In the same year they also set up a school for untouchable girls. Savitribai, along with Sagunabai, Fatima Sheikh and some male colleagues, taught in these schools. In the next four years, the Phules set up no less than 18 schools for women.

On the occasion of one of the annual examinations of his schools, Jotirao wrote, “To educate women and to cultivate their intelligence, to give them respect that they deserve and to take responsibility of their wellbeing is against the religious beliefs of Hindu people …” Here, he links education with respect and dignity and squarely blames the Hindu religion for suppressing women’s right to education.

In a letter dated 5 February 1852 and addressed to the then governor of Bombay, he says, “We are deeply impressed with the necessity and importance of ameliorating the condition of the Natives and enlightening minds through the means of female education and under this conviction have instituted a seminary with a view of promoting this beneficent object.” Jotirao was convinced that the overall improvement of society hinged on the education of women. In contrast, other reformers of his time wanted, at best, limited education for women to enable them to be better wives and mothers. For Jotirao, education was an inalienable part of women’s human rights. Elsewhere he says, “… If men do not come in the way of basic human rights of women, a free world would come into being and all men and women would be contented and happy.”

After a spate of schools, the Phules turned their attention to other social evils. Child marriage was the norm in society, particularly among the “upper” castes. Young girls were married to old men and more often than not became young widows. Widowhood spelt the death of their social and sexual life but ironically increased their vulnerability to sexual exploitation by the males in the family. They faced further disgrace if they happened to become pregnant as a result. This often left them with no choice but to take their own life, or their infant’s life, or both.

Moved by this state of affairs, the Phules opened their own home to pregnant child widows in 1863. They put up huge posters at the Brahmanwada, directly appealing to the young widows not to lose heart if they found themselves pregnant. They were invited to the Phules’ residence to deliver their child after which they could stay back or walk away. The Phules’ non-judgmental and empathetic approach made them stand out among their fellow reformers and earned them the ire of the brahmanical orthodoxy. Savitribai personally helped in delivering babies of more than 35 Brahmin women. The Phules also extensively wrote about the social evil of child marriages.

Jotirao Phule lashed out at the cruelty meted out to the Brahmin widows while letting the widowers remarry and traced the roots of this patriarchal discrimination again to the Hindu religious texts. The Brahmana reformers who discussed and debated enforced widowhood offered peculiar arguments against it, none of which had anything to do with the victims’ trauma. They seemed more concerned about the “disastrous” effects that the repressed sexuality of widows would have on the moral fabric of society if it was randomly vented, or about widows being deprived of the very purpose of their existence – motherhood – or about the anxiety of the parents and parents-in-law to keep them “pure”. At best, they felt keenly for the misery of the young widows. It was only the non-brahmana reformers who could see it for what it was – a blatant abuse of human rights in a caste- and gender-ridden society. This was probably because the latter were looking at these hierarchies from the bottom up.

Jotirao took a firm stand against gender atrocities, particularly sati. According to him, “The woman has to suffer a lot of hardships and pain when her husband dies. She has to carry her widowhood till her death. Often she used to burn herself in her husband’s funeral pyre. But have you ever heard of a man doing the same in grief over his wife’s death? Despite having a worshipping wife at home, men marry two to three women, but women once married to a man do not marry other men and bring them home.” Here again, Jotirao minced no words in attacking the patriarchal order that privileged men over women.

Living out their values

Savitribai and Jotirao were childless. There was immense pressure on Jotirao to remarry but he refused. His argument was, if he were responsible for the state of childlessness, would Savitri be allowed to remarry? This made Jotirao one of the very few reformers who actually practised gender equality in his personal life. The Phules chose to adopt an abandoned child of one of the Brahmin widows from their home. They named him Yashwant and educated him to be a doctor. By their unusual and unconventional act, the Phules openly challenged many pre-conceived notions of caste, lineage, motherhood, paternity and so on.

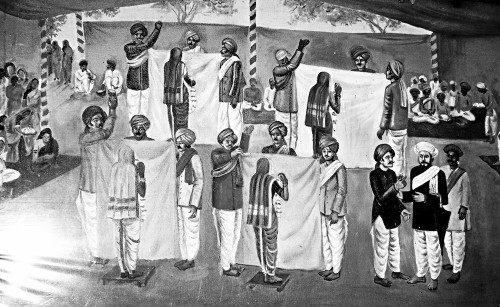

In 1873, Jotirao set up the Satyashodhak Samaj, a socio-spiritual, non-brahmanical movement that critiqued caste and gender. Satyashodhaks supported the struggle of women workers in Mumbai against their oppression both as workers and as women. On 25 March 1893, 400 women from Jacob Mills agitated against their male bosses. This was probably the first self-motivated struggle of Indian women workers for their rights. The Samaj took the lead in breaking the priestly hold over society by conducting marriages without Brahmin priests or religious rituals. The couple would merely exchange vows. Jotirao wrote these vows in 1887, replacing the traditional, Hindu religious marriage mantras. The vows comprise a demand from the bride to be treated with respect, an assurance from the groom to fulfil his bride’s demand and a joint pledge to dedicate their lives to the cause of the needy and the oppressed.

The first Satyashodhak marriage took place between Sitaram Jabaji Alhat and Manjubai Gyanoba Nimbankar and was conducted without pandits on 25 December 1873. The Brahmin priests approached the court against the Satyashodhak marriage system on the grounds that it deprived them of their fees and was an encroachment on their religious rights. Every such marriage resulted in a new legal suit. Jotirao did not lose courage. He fought all the cases with great tenacity. Though judgments in local and district courts went against him, he won the cases in the high court.

The Satyashodhaks, led by the Phules, firmly believed in inter-caste marriages as one of the means to break down the caste system. They personally supported people who chose to inter-marry. They also got several widows remarried, braving terrible opposition.

Satsar was a journal that Jotirao first published in 1885. It became a platform for the debates and discussions among the Satyashodhak members and reflected the ideological stand taken by the members on a range of caste and gender issues.

In the second issue of Satsar, Jotirao publicly supported Pandita Ramabai’s conversion to Christianity. He did so for two reasons. One, he saw it as an escape from an oppressive religion. Two, he saw in it an act of rebellion and assertion by a woman. In the same issue, he criticized the near-hysterical reaction to Tarabai Shinde’s Stree Purush Tulana, published in 1882, which is a scathing critique of male double standards and hypocrisy in sexual relations. Not just that, he defended her stand and whole-heartedly endorsed it. Jotirao was clearly attacking the privileges and immunity enjoyed by men in a patriarchal set-up.

Jotirao wrote the Sarvajanik Satya Dharma Pustak to provide the philosophical base to the Satyashodhaks and as an alternative to the classic Hindu texts. He emphasized equality between men and women in the rules he laid down for those who wanted to follow the path of Truth.

Jotirao did not use the common word “manus” (human being), but insisted on using “stree-purush”. He was the first to do so in India. Phule’s use of the phrase “sarva ekandar stree purush” – all men and women – revealed his gender consciousness and gender sensitivity. He did not subsume “women” under “men”. He traced the ideological roots of women’s oppression in India to the Hindu religion and women’s secondary position worldwide to organized religions.

In India, the religion of the wife is assumed to be the same as that of her husband. Jotirao made it clear in his Sarvajanik Satya Dharma Pustak that women and girls had freedom to choose their own religion. He treated women as individuals in their own right and not as someone’s daughter\wife\mother. In fact, he offered arguments as to why women are mentally and morally superior to men!

For Jotirao, Indian women are deprived of education, human rights and human dignity and the culprit behind this is the Hindu texts that advocate both caste and gender hierarchy, keeping Shudras, ati-Shudras and women in a state of perpetual backwardness.

Phules’ perfect partnership

The final testimony to Jotirao’s gender consciousness lies in the fact that he not only made Savitribai literate but also encouraged her to be a poet. Savitribai published her first poetry collection, Kavya Phule in 1854, much before Jotirao himself was out in print. Her poetry reflects the angst of the newly emerging educated woman whose modern sensibilities and aspirations are in conflict with the existing conditions. Indeed Savitribai is considered the first modern, radical Marathi poet. Many ideas that appear in Jotiba’s magnum opus, Gulamgiri (1873), and Shetkaryacha Asud (1883) were already there in Kavya Phule (1854). This clearly reveals that the Phules discussed these ideas even as Jotirao formulated them. On her part, she was receptive to these intellectual inputs and was the first to understand Jotirao’s genius. In a poem she hails him as the “rising sun on the untouchables’ horizon”, at least twenty years before the world does so!

Mahatma Phule passed away on November 28, 1890, leaving behind a rich legacy of ideas and action towards women’s emancipation. After his death, Savitribai continued his social and political work until her death in 1897. In the work of the Phules, there was harmony between ideas and action, theory and practice. In their life, there was much love and mutual respect.

Jotiba’s feminism stands head and shoulders over that of others who followed for the consistency between his feminist thoughts, words – both critical and creative – and deeds. It is therefore just and right to hail him as the father of India’s gender revolution.

Published in the November 2015 issue of the FORWARD Press magazine