For the Hindus, Ram is not only an ideal human being but also a highly revered deity. The vast corpus of literature on Ram and his life in Hindi, Sanskrit and other Indian languages projects him as a great man and a repository of exemplary qualities. If one wants to see what a brave and noble hero is about, one just needs to go through any epic on Ram. That is why treatises and poetry on him are not only read and heard with great devotion but theatrical presentations of his life also evoke great interest and enthusiasm. But there are people – and their numbers are not negligible – who do not agree with this glorification of Ram and challenge the belief that he was an epitome of great human qualities. They say that the insistence on putting Ram on a high pedestal has not only served to demean other characters of the story but has also led to his opponents being painted in the darkest hues and becoming objects of hatred. Whenever such people try to present their point of view in newspapers, magazines or books, they are branded as atheists, apostates and descendants of Ravan – the symbol of all evils. Their voice is muzzled and they are charged with hurting the sentiments of the Hindus. But against all odds, such people have not stopped voicing their opinions. If there are hundreds of books eulogizing Ram, there are quite a few which interpret Ramayana differently and give expression to the anguish of the characters that have been portrayed as weak or evil and reduced to pygmies before the grand personality of Ram. They expose the flaws in the character of Ram and bring to the fore the injustices and atrocities he had perpetrated. One such book is Sachhi Ramayana, which was banned temporarily by the Allahabad High Court on 14 December 1999 for not peddling the popular image of Ram.

For the Hindus, Ram is not only an ideal human being but also a highly revered deity. The vast corpus of literature on Ram and his life in Hindi, Sanskrit and other Indian languages projects him as a great man and a repository of exemplary qualities. If one wants to see what a brave and noble hero is about, one just needs to go through any epic on Ram. That is why treatises and poetry on him are not only read and heard with great devotion but theatrical presentations of his life also evoke great interest and enthusiasm. But there are people – and their numbers are not negligible – who do not agree with this glorification of Ram and challenge the belief that he was an epitome of great human qualities. They say that the insistence on putting Ram on a high pedestal has not only served to demean other characters of the story but has also led to his opponents being painted in the darkest hues and becoming objects of hatred. Whenever such people try to present their point of view in newspapers, magazines or books, they are branded as atheists, apostates and descendants of Ravan – the symbol of all evils. Their voice is muzzled and they are charged with hurting the sentiments of the Hindus. But against all odds, such people have not stopped voicing their opinions. If there are hundreds of books eulogizing Ram, there are quite a few which interpret Ramayana differently and give expression to the anguish of the characters that have been portrayed as weak or evil and reduced to pygmies before the grand personality of Ram. They expose the flaws in the character of Ram and bring to the fore the injustices and atrocities he had perpetrated. One such book is Sachhi Ramayana, which was banned temporarily by the Allahabad High Court on 14 December 1999 for not peddling the popular image of Ram.

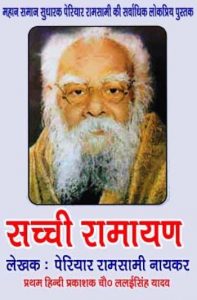

E.V. Ramasamy Periyar (1879-1973) wrote the book in question. He was a tireless freedom fighter, staunch atheist, brilliant socialist thinker, great advocate of prohibition and revolutionary social reformer. All his life, he tenaciously fought against untouchability, feudalism, usury, discrimination against women and imperialistic expansion of the Hindi language. He did not subscribe to the nationalism of the Congress and bitterly criticized the principles of Gandhi as “Brahminism by proxy”. He was the unchallenged leader of the Dravidian people and an unparalleled exponent of rationalism and logic in the region south of the Vindhyas. No one can possibly have any objection to him being described as the Ambedkar of the South. In 1925, he launched a newspaper called Kudiyarasu (Republic) in Tamil. In 1926, he founded the Self-Respect League and in 1938, rejuvenated the Justice Party. In 1941, he brought together all non-Brahmin parties under the umbrella of Dravidar Kazhagam and continued to work dedicatedly for social reforms till his last breath.

About 50 years ago, he wrote in Tamil a critique of Valmiki’s Ramayana, which is extremely popular in north India. His contention was that the epic gave undue importance to the Indian Aryan castes and humiliated the south Indian Dravidians by portraying them as cruel and violent oppressors. He also objected to the epic depicting Ram’s victory over Ravan as the victory of the divine over devil, good over evil and truth over falsehood.

The book was translated into English and was published under the title The Ramayana: A True Reading in 1969. This English version was rendered into Hindi in 1978 and titled Ramayan: Ek Adhyayan. All the three versions were well received as they introduced the readers to the aspects of the characters whom they deified that were hitherto not only unknown to them but were forbidden from even thinking about them. It should be noted that these books, while exposing the human weaknesses of the heroes of Ramayana, did not generate any kind of resentment or anger among the people. On the contrary, the people could now relate more easily to their idols, knowing that their idols were just ordinary human beings. This critique also made them sympathetic towards the plight of the characters that were the victims of oppression and injustice.

But the books, especially the Hindi translation, became an irritant to those who had made vending Ramkatha their business. Unless they projected Ram as an incarnation of god, the people wouldn’t accept his miracles without demur and revere him. If Ram becomes an ordinary human, he loses the power to free you from your miseries. Once that happens, who will listen to the Ramkatha and how will they earn their livelihood! That was why the court was told that the book hurt the sentiments of crores of Ram bhakts and should be banned. And banned it was. However, subsequently, lifting the temporary ban, the Allahabad High Court said, “We do not lend credence to the view that what is written in this book will hurt the religious sentiments of the Aryan people. What should be noted is that this book was written originally in Tamil and its objective was to show to the Tamil-speaking Dravidians that the Ramayana – by portraying north Indian Aryans Ram, Sita, Laxman, etc as noble characters and south Indian Dravidians Ravan, Kumbkaran, Shurpnakha, etc as despicable creatures – insulted the Tamils. It presents the Dravidians’ conduct and traditions as condemnable and lowly. The objective of the writer may have been to present the injustices done to his community rather than deliberately hurt the sentiments of the Hindus. This cannot be considered unconstitutional. The writer has used his constitutional right to freedom of expression, just as the lovers of Ramkatha have been using theirs in presenting Aryans as superior. Given this logic, tomorrow Dalit literature, which openly puts the savarna people in the dock for their inhuman behaviour with Dalits, can be banned.”

But the books, especially the Hindi translation, became an irritant to those who had made vending Ramkatha their business. Unless they projected Ram as an incarnation of god, the people wouldn’t accept his miracles without demur and revere him. If Ram becomes an ordinary human, he loses the power to free you from your miseries. Once that happens, who will listen to the Ramkatha and how will they earn their livelihood! That was why the court was told that the book hurt the sentiments of crores of Ram bhakts and should be banned. And banned it was. However, subsequently, lifting the temporary ban, the Allahabad High Court said, “We do not lend credence to the view that what is written in this book will hurt the religious sentiments of the Aryan people. What should be noted is that this book was written originally in Tamil and its objective was to show to the Tamil-speaking Dravidians that the Ramayana – by portraying north Indian Aryans Ram, Sita, Laxman, etc as noble characters and south Indian Dravidians Ravan, Kumbkaran, Shurpnakha, etc as despicable creatures – insulted the Tamils. It presents the Dravidians’ conduct and traditions as condemnable and lowly. The objective of the writer may have been to present the injustices done to his community rather than deliberately hurt the sentiments of the Hindus. This cannot be considered unconstitutional. The writer has used his constitutional right to freedom of expression, just as the lovers of Ramkatha have been using theirs in presenting Aryans as superior. Given this logic, tomorrow Dalit literature, which openly puts the savarna people in the dock for their inhuman behaviour with Dalits, can be banned.”

It has now been almost 50 years since this book was published in Tamil and three decades since its publication in Hindi and English. It has not evoked violent reaction anywhere. Then, why has the book suddenly become a threat to the Hindu community? What has changed? How is it possible that the Constitution gives people the right to freedom of religion but circumscribes their right to read about their religion? Will it be just if people are allowed to read the Ramayana and the Mahabharata but are barred from reading the critiques of these books? As for popular sentiments, should we care about the sentiments of only a particular section of society? If criticizing Ram or Sita is hurtful to some people, doesn’t what has been written in some Hindu religious scriptures about Shudras, Dalits and women hurt those sections? Another pertinent issue is that Periyar’s Sacchi Ramayana is not the only Ramayana that challenges the popular mythological stories, exposes the injustice done to the Dravidians in the name of Ravan and demands a just and humane consideration of their case. Another Ramayana was published in south India in August 2015. It analyzes the contents of Valmiki’s Ramayana from a sociological perspective and using credible logic proves that Ram was no different from other kings. Like other kings, Ram too harboured expansionist ambitions, exploited his subjects and was ready to do anything that served his interests. But here, we seek to view Ramayana from the perspective of Periyar.

Many things in the Ramayana defy logic. For instance, it says that despite having lived for 60,000 years, Dasharath could not free himself from sexual desires. It also hints that Dasharath had more than three wives. Periyar uses these quotations to contend that Dasharath was an amorous person and also that at that time, women were just objects of carnal pleasure. Dasharath did not love any of his wives – for, if he did, he would not have felt the need for other women. Kaikeyi had married him on the condition that her son would be made heir to the throne. Clearly, it was wrong on his part to hand the throne to Ram in violation of this condition. Ram also knew that Bharat, not him, was the true heir to the throne but despite that, he agreed to be anointed. This, Periyar argues, proves that Ram was power-hungry.

When Kaikeyi reminds Dasharath of the condition and insists that Ram be exiled, Dasharath tells him, “I am ready to fall on your feet if you give up the insistence on sending Ram into exile”. Periyar says that such slavish behaviour does not befit a king. He charges Dasharath with going back on his promise and with having been blinded by his love for Ram. As for Ram, Periyar says, he was cunning, both in word and deed. Valmiki’s Ram, according to Periyar, was a liar, a show-off and a thankless person. He writes that Ram was deceptive, harsh, greedy, kept wrong company and persecuted innocents. He says that if Ravan had these vices, so did Ram; then, how Ram could be good and Ravan bad. Periyar observes that the shrewd Brahmins gave the status of god to a dishonest, cowardly, incompetent and characterless person and now they expect us to worship him. He says that even Valmiki believed that Ram was not god and that there was nothing divine about him. But the Ramayana opens with the statement that Ram had elements of Vishnu in him. Ram performs many superhuman feats including freeing others from curses and having a dialogue with divine forces. Does this not show that he was equipped with superhuman powers?

As they did not get adequate respect and love from Dasharath, Sumitra and Kaushalya did not look after him. According to Valimiki’s Ramayana, when Dasharath passed away, they were sleeping and on being informed by the wailing slave girls, they got up at leisure. Periyar writes, “Look at these Aryan women! How careless they were in looking after their husband.” And then he goes on to analyze why they were so careless.

Periyar finds a hundred faults in Ram but considers Ravan’s character flawless. He says that even Valmiki praises Ravan and accepts that he had ten great virtues. Valmiki says that Ravan was a great scholar, a formidable warrior and a handsome man. He was compassionate, ascetic and magnanimous. When, according to Valmiki, Ram was “Purushottam” (perfect man), then why, Periyar asks, Ravan, who also had the same qualities, should not be considered, if not perfect, at least a good man? Ravan is blamed for abducting Sita but according to Periyar, Sita went away with him of her own volition. Going a step further, Periyar says that Sita went away with another man because she was fickle by nature and that Lav and Kush were Ravan’s sons. Periyar does not have a word of praise for Sita. He gives the following ten arguments to prove that Sita was, in no way, an ideal woman.

- The story of Sita’s birth lacks authenticity. She is described as “Bhoomiputri” (daughter of the Earth) and it is said that Raja Janak had got her from the womb of the Earth. Sita was the abandoned daughter of some unwed mother. The daughter of a woman of loose morals is likely to be wanting in character. Sita says, “Despite my having attained youth, no prince has come forward to seek my hand as there has been a stigma on me since my birth.” Sita had turned 25 but Janak was unable to find a suitable husband for her. He shared his anguish with Rishi Vishwamitra and sought his help. Then Vishwamitra took Ram – who was much younger to Sita – to Janak and Sita had no objection to marrying him. This proves that Sita was so dejected that she was ready to accept anyone as her husband.

- When Ram decided to go into exile, Sita refused pointblank to stay back in Ayodhya. The reason was that shortly after her marriage to Ram, Bharat had started humiliating Sita. Ram himself tells Sita that she was not worthy of Bharat’s admiration. Sita says, “I cannot live with Bharat because he disobeys me. What can I do? He does not like me. How can I live with him?” These admissions of Sita make her character suspicious. After all, why Bharat had taken a dislike to Sita? The obvious answer is that he suspected her character.

- Sita was crazy about ornaments and diamonds. When Ram is about to leave for the forests with her, he asks her to take off all her ornaments. She takes them off reluctantly but carries some with her without the knowledge of Ram. When Ravan takes her away, she drops these ornaments one by one. In Ashok Vatika, he hands over her ring to Hanuman to prove her identity. Apparently, she loved her ornaments so much that she was ready to disregard her husband’s orders to keep them. It also shows that she could have made immoral compromises for ornaments.

- She is a liar. Despite being older than Ram, she lies about her age to Ram and Ravan and claims that she is much younger. This puts a question mark on her character.

- Sita ensures that she is left alone in the forest so that Ravan can abduct her with ease. She sends Ram to hunt the golden deer and Laxman to save him so that there is no one around and she can do what she wants.

- Sita admonishes Laxman using harsh words. She even says that he desires to have her and that is why he is not going to save Ram. Such remarks betray her filthy mind.

- An outsider (Ravan) comes and praises the beauty of every part of Sita’s body, even the size and curves of her breasts, and Sita listens in silence. This shows her weak character.

- When Ravan is taking Sita away, she hurls all sorts of curses on him. Had Sita been a chaste woman and a virtuous wife, Ravan should have turned to ashes immediately. But that does not happen. And as soon as she enters the palace of Ravan, she begins to love him.

- When Ravan proposes her, she refuses but then closes her eyes and begins sobbing. This conduct is suspicious.

- Periyar gives two other proofs of Sita’s growing affection for Ravan. a) In the Bengali Ramayan of Chandrawati, Ram’s elder sister Kumkuwati tells him that Sita has drawn someone’s portrait but she does not show it to anyone and always keeps it close to her chest. Then Ram goes to Sita’s chambers and finds what his sister was saying is true and that the portrait is of Ravan. b) In C.R. Srinivasa Iyengar’s Notes on Ramayana, Ram catches Sita red-handed while she is drawing a portrait of Ravan.

Towards the end of the book, Periyar refers to the incident in which Ram asks Sita to proves her chastity. She refuses and chooses to enter the Earth. The worshippers of Ram cite this incident as the ultimate proof of Sita’s piety and chastity. But Periyar says that Sita gets sucked into the Earth as she fails to prove her chastity.

Towards the end of the book, Periyar refers to the incident in which Ram asks Sita to proves her chastity. She refuses and chooses to enter the Earth. The worshippers of Ram cite this incident as the ultimate proof of Sita’s piety and chastity. But Periyar says that Sita gets sucked into the Earth as she fails to prove her chastity.

Periyar asks whether such a Ram and Ramayana are worthy of respect and reverence. Periyar has written this book in the form of a long essay that begins with his views on the Ramayana, followed by a critique of all its characters.

Without mincing words, he says that Ramayana was not history but fiction. Ram was not a Tamil and he had nothing to do with Tamil Nadu. He was a pure north Indian. On the other hand, Ravan was the king of Lanka, which is to the south of Tamil Nadu. That is why Ram and Sita not only do not have any Tamil features but they are also devoid of all elements of divinity. Like the Mahabharata, the Ramayana is also a mythological story that was written by the Aryans to prove that they were noble by birth while the Dravidians were a base and vile people. Its main objectives were to prove that Brahmins were superior, that women had a secondary status and that Dravidians were condemnable creatures. The epic was deliberately written in Sanskrit, which was called “Devbhasha” (the language of gods), the study of which was prohibited for the lower castes.

The Aryans, Periyar says, present the Ramayana as a sacred scripture written by a great soul who had descended on the Earth to emancipate its inhabitants so that people readily believe what is written in it and never question its characters and incidents. When the Aryans invaded the ancient land of the Dravidians, they not only ill-treated and humiliated the Dravidians but to justify and glorify their conduct, they presented Dravidians as demons who created hurdles in the path of noble men. The Dravidians are shown as being lovers of liquor and meat, who did not allow ascetics to do penance, defiled religious rituals and abducted the wives of others. As they were evil incarnate, it was the duty of Aryan men to punish them. If the Tamilians praise such a Ramayana, Periyar says, they only justify their humiliation and hurt their self-respect.

Whenever educated Tamilians talk of Ramayana, they are generally referring to Kamban’s Ramayana, which is the Tamil translation of Valmiki’s Ramayana. Periyar believes that in his translation, Kamban has tried to hide the true nature of Ramayana and has twisted the tale to misguide Tamilians. Therefore, he recommends reading the translations of Anand Chariar, Natesh Shayiar, C.R. Srinivas Iyengar and Narsingh Chariar.

But it is regrettable that Periyar admires Ravan as blindly as Valmiki praises Ram. He accuses Valmiki of portraying women in poor light and ignoring them but he himself uses derogatory terms for Sita – just as Valmiki does vis-à-vis Manthra and Shoorpnakha. Why? Only because Sita is an Aryan woman? Does a woman not remain a woman if she is an Aryan? Similarly, often, while speaking for Dravidians, he is unjust to the Aryan characters of Ramayana. But despite many shortcomings, it is a book worth reading, if only because it presents the other side of the picture.

Courtesy Jan Vikalp magazine, Patna; September-October 2007 issue; edited by Premkumar Mani and Pramod Ranjan