The non-Brahmin Dravidian movement of 20th-century Tamil Nadu has a long, chequered history. Its origins can be traced to the Non-Brahmin Manifesto released in 1916. Reforms during this period chiefly centred on women and caste, though in a limited way. The Justice Party came into existence in 1917 to promote the political and educational advancement of the non-Brahmins. It came to power in the 1920 provincial elections, ushering in the first ever non-Brahmin government ministry. E. V. Ramasamy, better known as Periyar, was part of this slice of history.

Periyar, however, came into his own with his Self-Respect Movement in 1925. Its goal was to unite the non-Brahmin castes by instilling in them a sense of pride based on their Dravidian roots. The movement outlined its basic principles: no God, no religion, no rituals, no caste. To these, Periyar added his own sensibility – no patriarchy! The Self-Respect Movement’s long-term vision was to usher in a caste-free society. To this end, they had to confront all institutions that propped up caste, such as the brahmanical Hindu religion and brahmanical patriarchy. The beauty of Periyar’s struggle was that his personal growth brought him face to face with each of these institutions separately. Each became a fight in itself, for itself. Thus, he led the struggle against brahmanical Hinduism using rationality as the tool. Likewise, he opposed patriarchal practices with his own conviction that women were free beings in their own right and subservient to none.

Unlike the upper-caste reformers before him who merely dabbled in “women’s issues” without challenging the basic structure of patriarchy, Periyar questioned the monogamous family and the norms of chastity that enslaved women within it. Since marriage epitomized the subjugation of women, he insisted that marriage as an institution should be abolished and women set free.

Periyar’s conception and articulation of the Self-Respect Marriage (SRM) in 1929 was an ingenious master stroke. It projected marriage as a contract between equals irrespective of caste, class or religious considerations, without priests or even parental approval. It shifted “marriage” from the realm of the sacred to that of a contract between equals, from one that was “forever” to one that could be terminated by either party, from one that was divinely ordained to one that was self-contracted. He shifted the onus and jurisdiction of the SRMs from the family and community to the individuals concerned. The crux of the SRMs was gender equality and individual agency. This was nothing short of a revolution in the realm of thoughts and ideas and a leap in self-consciousness and self-awareness. In short, Periyar created the new man and woman.

Five decades before Periyar was born, the Phules had articulated a radical concept – the Satyashodhak Marriage Rites in Pune, Maharashtra – where the bride and groom recited their own secular, gender-equal mantras in place of the Hindu religious mantras. Periyar took this radical strand of self-determination to its logical end even though he had never heard of Phule.

The SRMs presided over by Periyar himself gave him a public platform to propagate his feminist ideas. There was no aspect of the man-woman relationship that he left unexplored. He wanted women to have complete control over their sexuality, fertility and labour. He believed in women having unlimited and unconditional freedom. In fact, he said and did everything to sabotage patriarchy. He specialized in scandalizing society and shaking it out of its complacency by making provocative statements like “women should cease having children if it comes in the way of their personal freedom”. He bluntly stated that women would never be free as long as “patriarchal masculinity” enjoyed currency. He wanted chastity and “character” to be applicable to both man and woman or neither.

He insisted that parents bring up their daughters in the same manner as their sons, even in matters of names and attire, and train their daughters in sports such as boxing and wrestling.

As far as contraception for women was concerned, he believed that it was a tool to set women free and put her in charge over her life. This perspective was radically different from that of his fellow reformers, who looked at women’s contraception with the interests of the family, community or nation in mind. In contrast, Periyar believed that only a woman could and should decide if she wants to have children or not, when she should have them, in or out of wedlock. He articulated all these thoughts in his talks, speeches and writings, which were compiled in the form of a booklet titled “Why the Woman was Enslaved”.

He spoke the language of radical feminism decades before the second-wave feminists in the Western world coined the term.

Apart from Self-Respect Marriages, the Self-Respect Conferences, women’s conferences and youth conferences provided yet another avenue to Periyar to articulate his gender concerns. The resolutions passed at these get-togethers were pro-women and gender-just.

Another USP of the movement was that women not only attended the women’s conferences but played an important role in the general Self-Respect Conferences as well – from organizing them, presiding over them to moving resolutions. The women activists of the movement clearly understood the link between caste and patriarchy. They drew parallels between caste oppression by the Brahmins and gender oppression by men. They saw religion as legitimizing and justifying both caste and gender inequality. All this was articulated by them in the various papers and journals of the movement. In fact, the title “Periyar” or “the Great One” was conferred on E.V. Ramaswami by the Tamil Nadu Women’s Conference held in Madras in 1938.

Periyar did not believe in ghettoizing women either in the public domain or the private one. He practised, in his own life, what he preached to women. He persuaded his newly wedded 13-year-old wife, Nagammal, to discard the “thali” or mangalsutra. He encouraged her to address him as comrade and took her along with him to every meeting and conference. Ditto, with his sister Kannamal. So much so that when Gandhi gave the call for picketing toddy shops to uphold prohibition in 1921, it was Nagammal and Kannamal who led the agitation in Erode. Even so, on the death of his wife in 1933, he expressed profound regret that he had not put into practice even a fraction of his feminist beliefs, in his marriage.

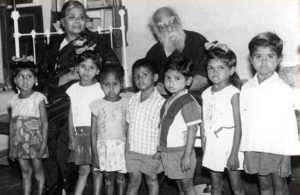

Another significant event in Periyar’s life was his remarriage at the age of 70 to Maniammai, his loyal secretary of six years, some forty years younger than him, in 1949, amid raging criticism and censure. He defended his move by declaring that it was not for sexual pleasure that he had married – he qualified the statement by stating that marriage was not mandatory for that purpose – but to entrust his life’s work, organization and property to her as he trusted her to carry on the work after him. He thus chose a young woman as an heir to his rich legacy of nearly a century of relentless battle against age-old obscurantism in Tamil society.

This was the ultimate testimony to his feminist praxis.