As Ambedkar has rightly argued, there is a religious-persecution angle on caste practices and untouchability. When brahmanical caste system and patriarchy were established in Kerala as religious norms by the 10th century, the Avarna or untouchables clung on to Buddhism and refused to submit to Brahmanism. That is why the adherents of Hindu Brahmanism resorted to inhuman, barbaric torture and public humiliations. Imposed on them by bloody violence, baring of breasts by Dalitbahujan women before the caste lords, especially the Brahmins, became a convention that lasted over a millennium.

Brahmanical patriarchy and its Savarna-subservient Shudra foot soldiers zealously enforced the practice in the name of the Sanatana Hindu religion and its tradition of “sacred purity”. This again entailed violent repression. In parts of Malabar and Kochi, it continued up to the mid 20th century, though the Shudra militia and petty barons were checked briefly by the Mysore invasions of the 18th century.

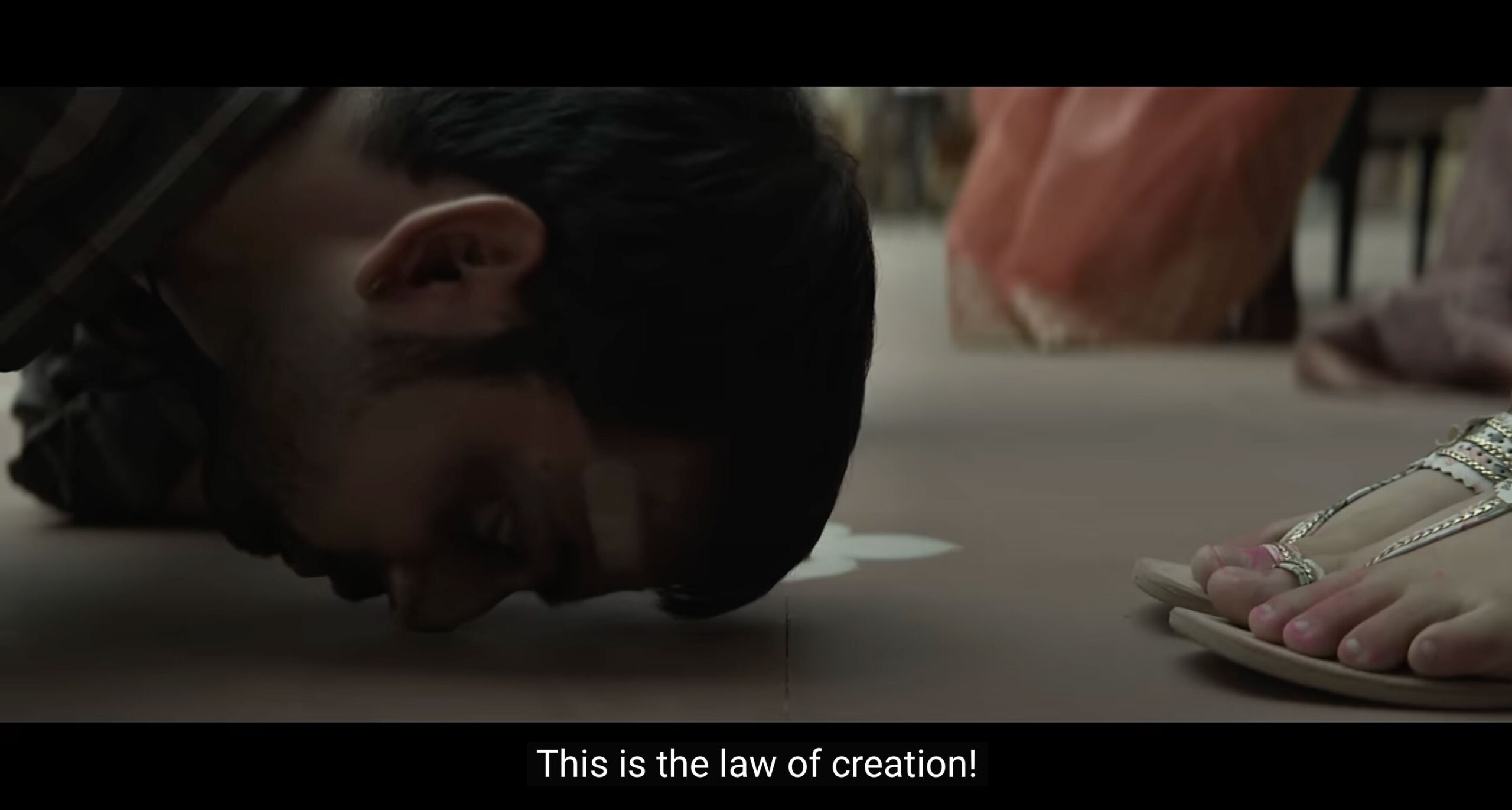

Those who practised the ethical and egalitarian traditions of Buddhism and Jainism were expelled as untouchables and slaves. Their humiliation was made a ritualistically public and performative social practice in their everyday life. The Avarna in general were prohibited from wearing decent clothes and using decent language. The caste system was inscribed on culture by controlling what they ate and wore and even their sexuality and body.

It was a religious and partly ethnic conflict that infuriated the Bhudevas, the earthly gods, or the Brahman. Those who refused to fall in line with the caste ideology of Brahmanism, including its stand on purity and pollution, and those who wouldn’t let their women become sex slaves of the high priests were kept outside the Varna system. Manipravala literature and Achi Charitams (tales of courtesans) emerged from these Brahman-Shudra alliances called Sambandha. The local elites who provided sex colonies and militia services to the priests were upgraded to the Shudra, the fourth Varna. These Shudra kaanakar (or overseers) and lords lived and died by the sword for the Varna Dharma.

Beginning of the end

This heinous Hindu caste practice came to an end in Nanjinad, in south Travancore, in the mid 19th century. Here, the colonial missionary interventions contributed to the Nadar rebellion that challenged the Savarna hegemony. The cultural groundwork laid by Ayya Vaikuntar, Narayana Guru and Ayyankali was inseparable from this protest that brought with it the possibility of social reform.

Though this practice of systematic public shaming ended in Travancore in the late 19th century and in Cochin the early 20th century, it continued even up to the second half of the 20th century in Malabar. In Thrissur district, Talapally taluk, this caste practice was alive even after Indian Independence. In 1952, Velathu Lakshmikutty, a brave woman belonging to the Avarna Ezhava community, led the agitation to end it. In the Manimalarkavu temple, in Velur, just a few miles east of Kechery in Thrissur, Avarna women had been forced to parade with their naked breasts as a religious festival ritual by the Nair caste lords of the Thazhekad petty kingdom that controlled the temple. The temple was a Buddhist shrine until the early Middle Ages. The taluk, now called Talpilly, was originally called Talapally, the head vihara or the leading pally, which clearly distinguishes the region as Buddhist before Brahmanism was established in the eighth or the tenth century.

Lakshmikutty, the defiant crusader against brahmanical patriarchy and its inhuman dictates on the gendered subaltern body, led a procession of decently dressed Avarna women, challenging the caste Nair lords and their Brahmin paternal priests. The Avarna renaissance organizations and the mostly Dalitbahujan early communist party were on hand to resist the casteist aggression from the Savarna men. Shockingly, this historic assertion of human rights and women’s dignity by Avarna women is still not part of Kerala history textbooks. It is an example of caste humiliations that continue in India even after Independence. It also busts the myth that caste feudalism and brahmanical patriarchy ended in Malabar with Mysore’s early-18th-century occupation.

Collective amnesia regarding key aspects of subaltern social struggle that created modern Kerala and the Kerala renaissance, or the indigenous democratic model, is proving to be fatal. The former caste lords are propping up their caste surnames to get into key positions in the government. The growing Hinduization discourses and Ramayana propaganda even in the media, especially on AIR and DD, are enslaving the minds of the Dalitbahujan and persuading them to imitate and follow their immediate caste superiors, the Shudra, in true Varnashrama Dharma fashion.

Published in the February 2016 issue of the Forward Press magazine

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of the Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) community’s literature, culture, society and culture. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +919968527911, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)