“The most authentic interpretation/explanation of caste-based discrimination, exploitation, oppression and violence comes less from research studies and more from holistic auto ethnographies.” (Caroline Ellis, 2011; Stanley L. Watkins, 2014). Auto ethnography is a methodology for analyzing personal experiences in a way that they can be accurately understood in terms of cultural experience. This is what Tulsi Ram wrote about his autobiography: “Murdhiya is not my autobiography; it is the autobiography of society of those times, including animals and other living beings. To my mind, autobiographies describe societies through the medium of a person.” (Vibhavari, 2015, p 82-83).

“The most authentic interpretation/explanation of caste-based discrimination, exploitation, oppression and violence comes less from research studies and more from holistic auto ethnographies.” (Caroline Ellis, 2011; Stanley L. Watkins, 2014). Auto ethnography is a methodology for analyzing personal experiences in a way that they can be accurately understood in terms of cultural experience. This is what Tulsi Ram wrote about his autobiography: “Murdhiya is not my autobiography; it is the autobiography of society of those times, including animals and other living beings. To my mind, autobiographies describe societies through the medium of a person.” (Vibhavari, 2015, p 82-83).

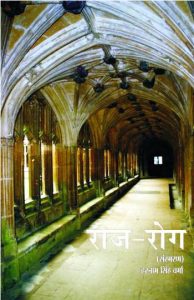

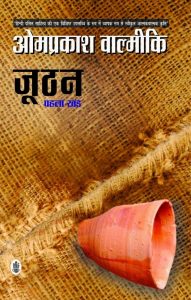

Keeping these factors in mind, the autobiographies/reminiscences of six writers have been included in this study. They are Om Prakash Valmiki (Joothan), Tulsi Ram (Murdhiya, Manikarnika), Balbir Madhopuri (Changiya Rukh), Harnam Singh Verma (Apne-Paraye, Raj Rog, Part-Dar-Part and the unpublished Syah-Safed), Temsula Ao (Once Upon a Life: Burnt Curry and Bloody Rags) and Lal Bahadur Verma (Jeevan Pravah Mein Behte Huye). The first three writers are Dalits, the fourth is an OBC, the fifth is a Christian Tribal from northeast and the sixth is the “control group” – a dwij writer. The reminiscences of Harnam Singh Verma and Temsula Ao are unique. Harnam Singh’s writings encompass the past, the present and the future and his satire is also impressively different from all the others. The discrimination, persecution, rejection and evasion these writers faced at the hands of dwijs in their personal and professional lives could not have been the same and are not. In this section of the study, we will try to understand the problems the Dalits and the OBCs face in acquiring education.

Importance of education

The mobility and dynamism of a deprived community is a function of the education of its members. This is true not only of Dalits but also of other backward peoples. They can grow in their lives only if they become educated. Tulsi Ram says that the Gurukul system was a tested tool for stopping the common people from acquiring knowledge and wisdom (Vibhavari, 2015, p 85). Harnam Singh goes a step further and contends that even today’s education is dominated by the dwijs and is designed to help the children of dwijs flourish and to push back the children of the deprived sections. (Apne-Paraye, 2015: Vishwavidhyalaya Ke Shikshak, Graduate Aur Postgraduate Ki Nazar Se). Lal Bahadur Verma never faced any discrimination while Temsula Ao did because of her poverty and not because she came from a particular tribe. The behaviour of dwij teachers with the three Dalit writers was reprehensible.

Exploitation by teachers

Exploitation by teachers

The behaviour of Om Prakash Valmiki’s “ideal teachers” with him was Dronacharya-like. His first three days in school were spent sweeping the school building and the sprawling playground surrounding it. On the third day, when he went straight into class and sat, the headmaster hurled expletives at him and gave him a sound thrashing. He started sweeping the ground again. His father, who was passing by, saw this and confronted the headmaster. The headmaster asked Valmiki’s father to take him home. The next day, early morning, Valmiki’s father complained to the village pradhan and it was at the pradhan’s intervention that he was freed from his sweeping assignment (Valmiki, Joothan, volume 1, p 14-16). He was routinely beaten up without any apparent reason (ibid, p 62). If he asked any question in the class, he was abused and thrashed and made a “murga” (a corporal punishment when the someone is made to squat, with the hands holding the ears from under the legs) (ibid, p 34-35). His arithmetic teacher called Valmiki to his home ostensibly to give him tuitions but made him do all sorts of odd jobs (ibid, p 72). Valmiki and other students of his community were given poor marks in practical exams (ibid, p 62). The other residents of the village too did not let go of any opportunity to place hurdles in his way. Just a day before he was to sit for his mathematics exam, Tyagi Pahalwan made Valmiki sow sugarcane in his field for the whole day. At the end of the day, the savarnas were served full meals while two rotis and a small slice of pickle was all he and the others of his community got (ibid, p 74). In Balbir Madhopuri’s case, his teacher sent him to his field miles away to work. He was ridiculed for being a chamar.

Valmiki’s classmates used to make fun of him. “He is a Chuhda, he eats the ‘maand’ [starch] of rice and pig. He wears used clothes. No matter how much he studies, he will remain a Chuhda,” they used to say (ibid, p 44). His Tyagi classmates used to hit him without any reason and used to thrown his bag in the mud (ibid, p 40-41). To be free from this torture, he made friends with a hefty Gujar classmate (ibid, p 26). His personality developed in this terror-filled atmosphere in school (ibid, p 63). Besides facing the barbs of his classmates and his teachers, Valmiki also had to endure beatings (Joothan, volume 1, p 12-13). If he came to school wearing clean clothes, he was ridiculed: “See that Chuhda, he is wearing new clothes.” When he wore soiled clothes, it was said, “Chuhde, move aside, you are smelly” (ibid, p 13). Valmiki was quiet by nature but the abuses he had to face at the hands of his classmates, teachers and others made him an introvert. He turned irritable and whimsical (ibid, p 13).

Poverty comes in the way of education

Poverty comes in the way of education

There were other hurdles too. Valmiki’s home lacked an atmosphere of reading and writing. Frequent social gatherings were also a problem, especially at the time of examinations (ibid, p 75). After clearing class five, he could be admitted to Barla College in his village only after his widowed “bhabhi” sold off her anklet. In the new school, he became friends with two or three peers and the psychological pressure due to the barbs hurled at him eased somewhat. Though he was good in studies and had high organizational abilities, he was kept away from the events held in the college. One day, while visiting Muzaffarnagar with his father, he bought a copy of the Gita from a shop. He read it and what struck him was the ritualism it promoted. He sought the help of one of his teachers to clear his doubts but was snubbed with a “don’t-try-to-become-a-Brahmin” comment. (ibid, p 78)

Valmiki opted for the Science stream at the Intermediate level. There too, a teacher, Om Dutt Tyagi, consistently reminded him that he was a bhangi. His classmate Ram Singh Chamar was the brightest student of the class but was always harassed (ibid, p 80). Frustrated, Valmiki and Ram Singh wrote a pen portrait of Om Dutt Tyagi, which obviously was not flattering. One day, Tyagi asked Ram Singh to hand him a book that had, coincidentally, the pen portrait hidden between its pages. When he saw it, he was infuriated. He first gave Ram Singh a thorough thrashing in the staff room and then took him to the principal, who also shamed him. Fortunately, the principal let him off with a warning (ibid, p 81).

When Valmiki cleared the high school examination, his family gave a feast to the entire village. Chamanlal Tyagi came to his house to congratulate him, took him to his home, gave Valmiki something to eat in his utensils and did not allow him to wash the used plates (ibid, p 77).

Valmiki’s elder brother Jasbeer was working with Survey of India in Dehradun. He asked Valmiki to come to Dehradun (ibid 83-84). It was with great difficulty and after someone put in a word for him that Valmiki could get admission to the DAV College there (ibid, p85). There too, he was ridiculed over his clothes he wore till he sought the help of Thapa, a Pahadi friend. After Thapa used his physical prowess to teach one of Valmiki’s classmates a lesson, the news spread like wildfire and thereafter no one would dare make fun of Valmiki. But a financial crisis was always looming large and the evenings of Valmiki were spent working to earn a bit.

Tulsi Ram’s experience stands out

Of the three Dalit writers, two had to give up education midway due to the poor financial condition of their families, exploitation and discrimination by savarnas and teachers, and harassment in general. Only Tulsi Ram could leapfrog these hurdles and, with sheer hard work and help from some of his friends, complete his PhD. Valmiki and Madhopuri did not resist discrimination, harassment and derision. Tulsi Ram not only resisted but fought back too. Once, while he was being thrown out from a dharmashala for being a Dalit, he almost hit the person concerned with a wooden instrument. He also threatened that he would not pay the rent of the room. Tulsi Ram has titled the chapter in his book about his primary education as “Murdhiya Ka Skooli Jeevan” because he wanted to underline that what he went through during his school days affected his future.

He has analyzed his school experiences in the context of the social, religious, economic and political atmosphere of Murdhiya. Tulsi Ram studied in his village and in Azamgarh. Murdhiya relates his experiences of these two places while Manikarnika is about his life in Banaras. His family members, including his father and his short-tempered uncle, were a hindrance to his getting an education. In his geographical and cultural realm, the Brahmins had spread the belief that becoming too educated could drive a person mad. During his school, college and university education, Tulsi Ram did face classmates and teachers who harassed him due to his caste but he also had the company of Dalit and savarna friends who supported him and helped him complete his education. In Banaras, where he was both a student and a professional, he upgraded his lifestyle and personality.

He has analyzed his school experiences in the context of the social, religious, economic and political atmosphere of Murdhiya. Tulsi Ram studied in his village and in Azamgarh. Murdhiya relates his experiences of these two places while Manikarnika is about his life in Banaras. His family members, including his father and his short-tempered uncle, were a hindrance to his getting an education. In his geographical and cultural realm, the Brahmins had spread the belief that becoming too educated could drive a person mad. During his school, college and university education, Tulsi Ram did face classmates and teachers who harassed him due to his caste but he also had the company of Dalit and savarna friends who supported him and helped him complete his education. In Banaras, where he was both a student and a professional, he upgraded his lifestyle and personality.

Temsula Ao’s education in Christian school

Temsula Ao’s case was altogether different from the other writers because she studied in Christian schools and stayed in their hostels. She spent her early days under the tutelage of a British officer, who was also her landlord. After her parents’ death, her brothers educated her with great difficulty, even while living away from her. But the sisters superior and matrons of the schools and hostels misbehaved with her. This is the case in most missionary institutions, especially with poor students. Missionary institutions invariably provide good education but they are regimented enough to send shivers down the spine of many. As she was poor, Temsula was made to apply cow dung to the floor of the hostel as well as of the school and had to carry bucketsful of excreta and empty them at a distance. She neither had clothes to protect herself from the cold nor a proper bed. She had to lead a very harsh life in the educational institutions.

Caste patronage in school, problems in college

Caste patronage in school, problems in college

Harnam Singh’s educational life had a different hue. His first two years were spent in a private school run by his maternal uncle and later he was admitted to a government school, whose headmaster was a Kurmi and the only other teacher was his maternal uncle. Most of the students were also Kurmis. His problems began when he joined the Chhapra College at Fatehpur. Although the college had been established mainly with the resources provided by the Kurmis, its management was in the hands of dwijs. The principal Uma Shankar Pandey was a diehard Brahmin who used to humiliate students like Harnam Singh in public. This made Harnam Singh anti-dwij, and this stance evolved after he came in contact with Lohia (Harnam Singh Verma, Apne-Paraye, Chhapra College).

Smooth sailing for dwijs

Lal Bahadur Verma (Jeevan Pravah Mein Behte Huye) faced no discrimination while pursuing his education, either in India or abroad. Due to the contacts of the Kayastha caste, into which he was born, he didn’t have much difficulty in obtaining degrees from Gorakhpur, Lucknow and Paris universities. He shifted from Gorakhpur to Lucknow because one of his married woman classmates had moved to Lucknow! Verma got two PhDs – one from Gorakhpur University and the other from Paris University. There is no doubt that he is an outstanding historian but he could teach in Allahabad and North-Eastern Hill University because after Brahmins, the Kayasths have always been the most influential community in educational institutions. (Lal Bahadur Verma,)

This is an excerpt from a long essay based on the comparative study of six autobiographies.

For a deeper understanding of Bahujan literature, see Forward Press Books’ The Case for Bahujan Literature. The book is available both in English and Hindi. Contact The Marginalised, Delhi (mobile: 968527911).

Or, find the book on Amazon:

The Case for Bahujan Literature (English edition), Bahujan Sahitya ki Prastavana (Hindi edition)

And on Flipkart:

The Case for Bahujan Literature (English edition), Bahujan Sahitya ki Prastavana (Hindi edition)