Dr Ambedkar had a mastery over many disciplines and law was one of them. Ambedkar would spend hours and days poring over the laws and constitutions of different countries of the world. From his student days, he had great interest in developing an understanding of the ancient and the modern laws of India and the world. With time, he became an expert on different aspects of law and forged ahead of his contemporary jurists.

Ambedkar and contemporary politics

By the beginning of the 19th century, law had started emerging as a profession in many countries of the world. The contours for teaching and learning law were being drawn so that specialists in the law could be produced. New laws, rules and norms were coming into force. The countries which had thrown away the yoke of imperialism had started writing their own constitutions. In India, studying and practising law came to be associated with prestige and influence towards the end of the 19th century. Indians, especially those from well-off, upper-caste families, began studying law. Initially, students of law had no option but to pursue their studies in foreign lands, for there were few, if any, institutions teaching law in the country. By the 20th century, law had become a very prestigious profession in India and a degree in law became the dream of students. In India, almost all the leaders at the forefront of the freedom movement were trained in law. They included Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Lala Lajpat Rai, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, Motilal Nehru, Jawaharlal Nehru, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, Vallabh Bhai Patel, Madan Mohan Malaviya, Dr Rajendra Prasad and of course, Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar. They gave independent India a strong foundation. Ambedkar did not directly participate in the freedom struggle because other national leaders cold-shouldered him for the stand he took on social, economic and political issues. All his life, Ambedkar continued to be a bitter critic of both the British imperialists and the Indian national leaders. He was outspoken on issues, including those affecting the Untouchables (Dalits), Backwards, women and labourers. He turned them into national issues and suggested launching movements to highlight them. But other national leaders were averse to the idea. It would not be an exaggeration to say that Ambedkar was the most brilliant jurist among all of them.

Quest for knowledge and study of law

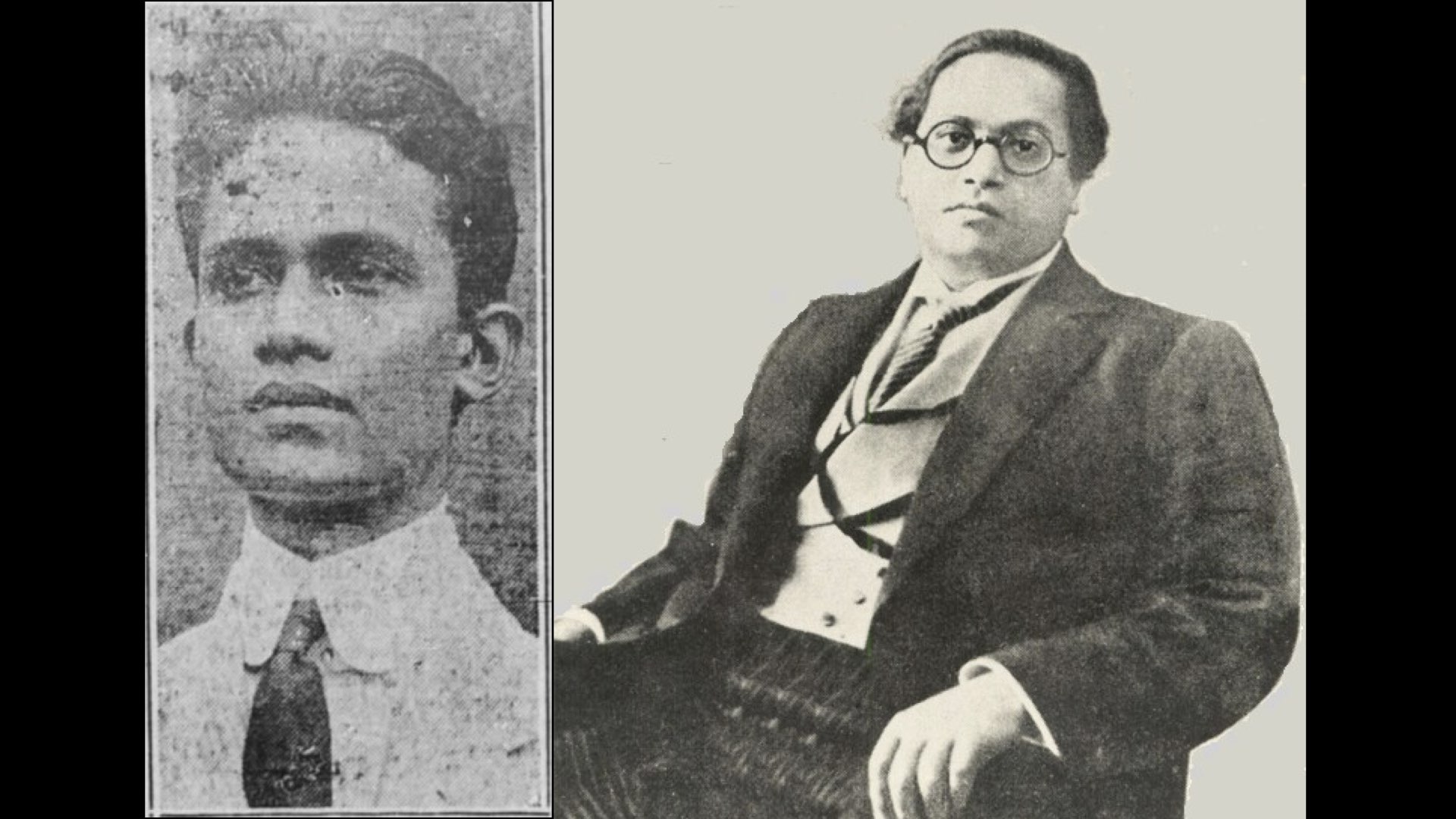

Ambedkar completed his primary education from Satara’s High School. He did his matriculation from Elphinstone High School, Bombay, and passed his class 12th and undergraduate examinations in humanities from Elphinstone College, Bombay, in 1909 and 1913, respectively. As he had an excellent command of English, Maharaja Sayajirao Gaikwad, the ruler of Baroda, sent him for further studies to Columbia University, USA, on an annual scholarship of 230 British pounds. He majored in economics and sociology for his postgraduation, before obtaining a doctorate in economics. He then headed to London because he wanted to become a lawyer so as to be economically independent. In October 1916, he was admitted to Gray’s Inn for Law. His quest for knowledge led to him poring over books from 8am to 5pm in different libraries of London. He was so single-minded in his pursuit of knowledge that he often skipped his meals. His thirst for knowledge wasn’t quenched till his last breath. His life was characterized by rigorous scholarship, intense self-respect, great dreams, lofty ideals, incessant hard work, broadmindedness and a spotless personality. He wanted to obtain another degree in Economics. But his study grant was for only three years. At his request, it was extended by a year. But his request for a further extension of two years was turned down and he was forced to return to India. But Ambedkar had obtained permission from the universities and institutions concerned to renew his studies within a period of four years. Shahu Maharaj offered to sponsor him.

On 30 September 1920, Ambedkar was back in London to continue his studies at Gray’s Inn. He spent a lot of time among the books and documents in the University General Library, Goldsmith Library of Economics, British Museum and India Office Library. He never allowed theatres and restaurants to distract him. Karl Marx, Lenin, Giuseppe Mazzini and Savarkar had also studied in the British Museum Library. On 28 June 1922, Ambedkar became a Bar-at-Law. What is noteworthy is that with his two doctorate degrees (PhD and DSc) in economics and Bar-at-Law, Ambedkar had the highest qualification among the Indians and Asians of his times. There was no one in the Indian sub-continent who could match his academic accomplishments. After completing his education, Ambedkar immersed himself in reflecting on the socio-economic problems of the world. There is no doubt that his life as a student was full of struggles. Gail Omvedt has described his scholarship as “Promethean” (rebelliously creative and innovative).

Ambedkar as a justice-loving lawyer

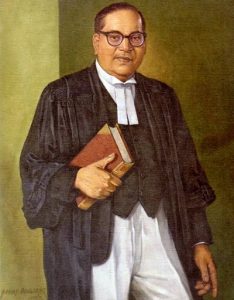

After Ambedkar’s return from London in 1923, he had to fend for his family, which included his wife, his children, his sister-in-law and nephew. He wanted to practise law but for that, he needed to be registered with the Bombay High Court. He did not have the money to pay the registration fee. His friend Naval Bhatena came to his rescue and gave him the requisite Rs 500. In 1923, he was admitted to the Bombay Bar Council and began his practice. He pleaded in the Bombay High Court as well as in the district courts of Thane, Nagpur and Aurangabad. But soon, the economist Ambedkar overwhelmed the lawyer Ambedkar. He wanted to do social work but had no time to spare. In order to pursue his career as a lawyer, he had turned down the offer of a Rs 2500-a-month job in the British Government. He had also refused to join the Kolhapur State Services. Ambedkar wanted to have an office but again he lacked finances. With the help of his friends, he rented a small room at the Social Service League, Poyabaodi, in Bombay, and later moved to the first floor of Damodar Hall, Parel. A portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte hung from his office wall.

Now, he had an office but he was not getting cases due to the jaundiced attitude of the Hindus towards him. Some of his friends tried to help him but it was months before he got his first case and that too of a Mahar. Lokmanya Tilak’s nephew also helped him. But the greater faith of the litigants in British lawyers and non-cooperation from high caste Hindus came in the way of Ambedkar. Despite all these odds, he was determined to achieve success in the profession. “I will become a judge of the High Court”, he would say. He had a penchant for buying books and that made his wife Ramabai’s task of running the household more difficult. But slowly, things began looking up once his office and his library had been set up and with the support of his friends and Mahars. Due to his poverty and “low-caste” status, he had to face many bitter experiences. For the likes of Nehru, it was easy to give up practising law to participate in the national movement, for they had the backing of their prosperous families. But for a poor and ‘low-caste’ person like Ambedkar, it was not easy to do so, for he had to run his family too. He had to keep working.

In 1926, Ambedkar got two important briefs. One was about Dinkarao Jawalkar’s book Deshanche Dushman (Enemies of the Country) and the other about Philip Sprat’s book India and China. Lokmanya Tilak, Vishnushastri Chiplunkar and their supporters had been spreading disinformation about Jotirao Govindrao Phule. Jawalkar, in his book, described Brahmanvadis like Tilak and Chiplunkar as “enemies of the country” and declared that Gandhi was a much better alternative to them. Jawalkar had written his book to answer Phule’s critics. A case was filed against Jawalkar. Despite there being no direct evidence of Phule having embraced Christianity, the judge ruled in favour of Tilak and co. Ambedkar’s argued that the judge who had given the judgment was prejudiced in believing that Phule was a Christian. In October 1926, Ambedkar won the “enemies of the country” case, which was perceived as a battle between the brahmanical and the non-brahmanical forces. This victory augmented Ambedkar’s stature. Tilak’s son Shridharpant Tilak became his follower and friend. Tilak was pro-Brahmin but Shridharpant was the president of a branch of Samaj Samta Sangh founded by Ambedkar and, unlike his father, was opposed to untouchability and the chaturvarna system. Hounded by his relatives and brahmanical elements, he ultimately committed suicide. Ambedkar said that Tilak’s son and not Tilak was the “real Lokmanya”. Ambedkar also won Philip Spratt’s case. Spratt was a British communist who was sent to India to spread communism here.

In 1933, Ambedkar pleaded another historic case, which had international implications. He pleaded the case of Raghunath Dhondo Karve, son of Dhondo Keshav Karve and the editor of Region magazine. Karve, through his magazine Samajswasthya, spread awareness on sex-related issues. He was charged with spreading vulgarity. Ignoring the stiff resistance of reactionaries, Ambedkar pleaded in defence of Karve. He argued that “vulgarity is not in the content but in the expression”. What is vulgar and what is not does not depend on its meaning but in the way something is said or written. He marshalled extensive arguments about the meaning of vulgarity but lost the case. But his arguments showed that he was willing to study in depth and understand any issue at hand. Ambedkar was an independent thinker and a supporter of progressive ideas. He defended communist writer Spratt; he rose to the defence of Jawalkar, who had lost to the brahmanical forces; and ignoring the aggressive posturing of the conservatives, he took up the case of Karve and defended his right to spread awareness on sex-related issues. It shows that he was justice-loving, had a deep understanding of the law and was devoted to his profession.

A large number of people used to gather to see Ambedkar appear in court. His career as a lawyer was historic and inspiring. He was very generous and liberal with his clients. Hindus, Christians, Muslims, people of all castes and classes, workers, factory labourers and small shopkeepers approached him for litigation. Even prostitutes wanted him to plead their case. He had a formidable knowledge of the law and was capable of presenting lucid and convincing arguments. His office had copies of the crucial judgments of all the high courts in the country.

Initially, Justice John Newmont, a judge of the Bombay High Court, was hostile to Ambedkar but gradually, as Ambedkar acquired the reputation of a good lawyer, Newmont became his admirer, especially because of the way Ambedkar argued criminal appellate cases. On occasions, he invited Ambedkar for tea. Attorney-at-Law N.H. Pandiya and B.G. Kher, who were the editors of Bombay Law Journal, invited Ambedkar to become a member of the editorial board of the magazine. In 1927-28, he was a special invitee of the advisory and editorial committee of Bombay Law Journal. In October 1928, he quit the committee as he increasingly occupied himself with the task of transforming society.

By the 20th century, secular laws had started taking the place of Smriti laws. Ambedkar’s laws replaced Manusmriti’s laws. On 25 September 1927, when Ambedkar joined his Hindu and Dalit supporters to publicly burn Manusmriti, he posed the biggest cultural challenge to the antiquated laws. This historic burning of the symbol of Brahmanism, casteism and cultural slavery brought Ambedkar on a par with Gandhi. Although he wanted to lead the life of a professor and a scholar, circumstances sucked him into politics.

Renowned professor of law

Ambedkar could not earn enough as a lawyer, so he started looking for a teaching job. From June 1925 to 1929, he taught commercial law at Batliboi Accountancy Institute as a part-time lecturer. Starting in June 1928, he taught in Government Law College, Bombay, for about a year. He also earned some extra income by evaluating the answer sheets of Bombay University examinations. Nationalist sentiment was at its zenith in the 1920s and he became a victim of it. He presented a memorandum before the Simon Commission as a representative of Dalits when the national leaders were boycotting the commission. As a result, nationalist students began boycotting his classes. His supporters, however, declared that the memorandum was the “Manifesto of the Human Rights of Dalits”.

In 1933, Ambedkar was appointed a “scholar” in the Department of Law and Humanities of the Bombay University. In June 1934, he returned to the Government Law College as a part-time lecturer. He wrote brief comments on the British Constitution as part of preparing his lectures. Newmont was very impressed with his work as a lawyer in criminal appeals and wanted to appoint him principal of the college. He was appointed to the post on 2 June 1935. He taught jurisprudence there. Newmont was very happy with the appointment. At the time, this post was considered a stepping stone to judgeship of the High Court. One of the quips that went around then was that if Ambedkar continued teaching in the college, the walls of the college, unable to hold the intensity of his thoughts, would collapse. Acharya Ishwardutt Medharithi described him as a “fearless leader of the youth”.

Ambedkar presented a plan to the Bombay government for improving the academic standard of the college. He wrote an article titled “Thoughts on improving law education in Bombay State”. The article elaborated on various aspects of law education, including curricula, subjects, and the age at which students should begin studying the law, and on how to polish the linguistic skills and logical reasoning of the students. He believed that law should not be taught only at undergraduate and postgraduate levels but it should be introduced to the student after he passes the tenth grade examinations. He said that if that was done, students would be able to make up their mind about the profession after clearing their matriculation examinations and start specializing in the subject of their choice. He also suggested that law curricula should also include sociology, psychology, logic, and public speaking, command of language and felicity of expression. His article titled “Dr Ambedkar’s analysis of decisions of Privy Council in the period 1829-31” dwelt on ways to develop an understanding of the law. He emphasized the interdependence of various disciplines. The January 1936 issue of the magazine of the college praised Dr Ambedkar’s deep understanding of law. “Dr Ambedkar is a well-known scholar who has studied economics with great diligence. He is famous as an authority on Constitutionalism in India and elsewhere.”

In May 1938, he resigned as principal of the Law College. The monthly bulletin of the college said, “The students had great regard for Dr Ambedkar’s knowledge and his skills as a teacher. His lectures were the thoughtful gist of his wisdom. His thoughts on jurisprudence were always revolutionary.” Was this praise only a formality or did he really deserve it? His radicalism came through in his writings and speeches. For example, he wrote in Annihilation of Caste: “The idea of law is associated with the idea of change, and when people come to know that what is called Religion is really Law … they will be ready for a change, for people know and accept that law can be changed … Hindus must … recognize that there is nothing fixed, nothing eternal, nothing sanatan.”

A jurist with no equals

Ambedkar was not only a professor of law and jurisprudence and an accomplished lawyer but he had a vast legislative experience as well. He was a member of the Bombay Legislative Council from 1927 to 1939 and the Labour Member of Viceroy’s Executive Council from 1942 to 1946. As the Labour Member he worked for the welfare of the workers. But even earlier, he had fought against exploitation of the workers by capitalists and the government. He analyzed caste by keeping caste at its centre. He agreed that a division of labour was essential for the functioning of any civilized society but argued that a birth-based division of labour was unnatural. He said that the caste system limited a person’s capability and skills. In Ambedkar’s words, “Caste system is not merely a division of labour. It is also a division of labourers.”

Whenever he got an opportunity, he went about doing the groundwork for laws meant for protecting the rights of labourers. In 1934, he founded the Bombay Kamgaar Sangh and in 1936 he became the president of Nagar Palika Shramik Sangh. His first political outfit was called Independent Labour Party. In 1937, he presented bills in the Legislative Council for the abolition of Khoti, Mahar Vatan and Halai systems, which were meant to perpetuate feudal, casteist and religious exploitation, and campaigned against them. He joined hands with communists and others to oppose the Industrial Disputes Act of 1938, which sought to limit the right of the workers to strike, and achieved historic success. As the Labour Member, he was in charge of labour, irrigation, power, social work and mines. He had the working hours of the industrial labourers reduced from 14 to 8. He also introduced the provision for paid leave and had employment exchanges established for skilled and semi-skilled labourers. He played a key role in getting bills on Employees State Insurance, review of the parameters for fixing wages of labourers, labour welfare fund, minimum wages, maternity leave for women and many other welfare measures passed and also had them implemented. He did not do all this for any political gain and there was no difference between what he practised and what he preached. Besides promulgation of labour laws and policymaking, he played a key role in the formulation of water and energy policies and in economic planning. All this made him the “creator of modern, scientific India” (aee Babasaheb Ambedkar: Sampoorna Vangmay, Volume 18).

He was appointed the first law minister of independent India by prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru. As the law minister, he had laws passed to grant rights to the deprived sections, gave them equal status, strengthened their liberty and sought to end the notions of high and low. These laws were milestones in the history of India. On 29 August 1947, he was elected chairman of the drafting committee of the Indian Constitution. The Constituent Assembly had members from all classes and castes. The Shudras, the Untouchables and the women, who were considered unworthy of education, worked together along with the others to produce the best constitution in the world. The Indian Constitution is the longest written constitution in the world but it has enough flexibility to deal with the changing times. Ambedkar faced untouchability, humiliation and demeaning behaviour during his student days and later as a lawyer and as a professor. When he joined public life, he drew flak for criticizing Gandhi and for being a stooge of the British. But India chose this man who had burnt the Manusmriti – the symbol of the varna system, caste system and social disharmony – to write its Constitution. Centuries ago, Manu had conspired to deprive the Untouchables, Shudras and women of education and other rights through his code of social conduct. But one of the Untouchables (who are now called Dalits, though untouchability continues to linger on in Indian society in many forms) became the creator of India’s highest code of law. India emerged as an important democratic republic in the comity of nations. Even Ambedkar’s ideological opponents could not help but praise his excellent and peerless work on the Constitution.

Some Hindu leaders compared Ambedkar with Manu and branded the Constitution as “Bhim Smriti” and “Mahar Law”. They said Ambedkar was a “modern Manu”. But this comparison was entirely unwarranted. There were fundamental differences between Manu’s laws and the Constitution that Ambedkar had drafted. Ambedkar had a very clear and cogent understanding of the nature of the law and of laws made for and by human beings. Manu had created a set of unequal social codes that were meant to protect the privileges of the Brahmins by granting them divine status. He had scripted a conspiracy. For Ambedkar, there was nothing divine about laws. They were entirely human creations. For Manu, as the laws were divine, they were eternal, unchangeable and infallible. For Ambedkar, laws were meant to fulfil the needs of society and could be changed to keep pace with the times. Manu’s laws were meant to serve the interests of the Brahmin and Kshatriya varnas (classes), while Ambedkar’s laws were for everyone – for Hindus, for Muslims, for Christians and Sikhs – and they did not brook any discrimination on grounds of birth, gender, race, religion, caste, creed, class or region. The world wholeheartedly praised the values of justice, liberty, equality and fraternity embedded in the Indian Constitution. The Indian Constitution became the guiding light of other newer independent nations too. It became a symbol of humanism.

It was Ambedkar who laid the foundation of the laws giving equal status and rights to women. He had played a seminal role in freeing women from the shackles of patriarchy. A committee was set up under the chairmanship of Ambedkar on 9 April 1948 to study the Hindu Code Bill. The Hindu Code Bill was prepared by Benegal Narsing Rau. Ambedkar studied the earlier legislations regarding women’s rights, besides Hindu scriptures, ancient texts, Smritis and other codes, and strengthened the provisions of the Bill. Ambedkar hoped to secure women’s right to property, ban polygamy, allow divorce on grounds of domestic violence and infidelity, and provide for inter-caste marriages and adoption through the Bill. This epoch-making piece of legislation had to face stiff resistance from the conservative Hindus.

Initially, both Nehru and Ambedkar worked together to demolish the arguments of the conservatives but later Nehru backed out. Even women, who were living in slave-like conditions for centuries, began opposing the measures mentioned in the Bill. Faced with opposition from both inside and Parliament and Nehru’s refusal to issue a whip to facilitate the passage of the Bill, Ambedkar declared that Nehru was unwilling to let the Bill passed, had divided it into many parts and had surrendered to the obscurantists. He then resigned his post. In his letter of resignation, Ambedkar also raised other issues like failure of the government to set up the Backwards Classes Commission; him not being given the charge of the planning ministry; and the foreign policy of the Nehru government. Ambedkar, who had written the world’s best constitution just a year earlier, was not even allowed to read his resignation letter in the Lok Sabha. He had to give copies of his letter to the members and journalists. He wrote in his resignation letter: “The Hindu Code was the greatest social reform measure ever undertaken by the legislature in this country. No law passed by the Indian Legislature in the past or likely to be passed in the future can be compared to it in point of its significance. To leave inequality between class and class, between sex and sex, which is the soul of Hindu Society untouched and to go on passing legislation relating to economic problems is to make a farce of our Constitution and to build a palace on a dung heap.”

A few years later, with Nehru’s efforts, the bills that Ambedkar drafted for securing the interest of women were passed in bits and pieces. The Hindi Marriage Act was passed in May 1955, Hindu Succession Act in May 1956 and the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act in December 1956. In 1961, the Dowry Prohibition Act was passed.

After Ambedkar’s unexpected defeat in the 1951-52 elections, his influence on the political scene in India started waning. But his stature continued to rise in the international arena. Two more degrees were added to the long list of his academic accomplishments. On 5 June 1952, the Columbia University conferred on him an honorary doctorate in law. The citation for the degree, besides recounting his academic achievements, described Ambedkar as the maker of the Indian Constitution, a member of the Rajya Sabha, a former minister, a leading citizen of India, a great social reformer and a vigilant protector of human rights. Osmania University conferred on him an honorary doctorate in literature on 12 January 1953 for his achievements, leadership and his role in the making of the Indian Constitution.

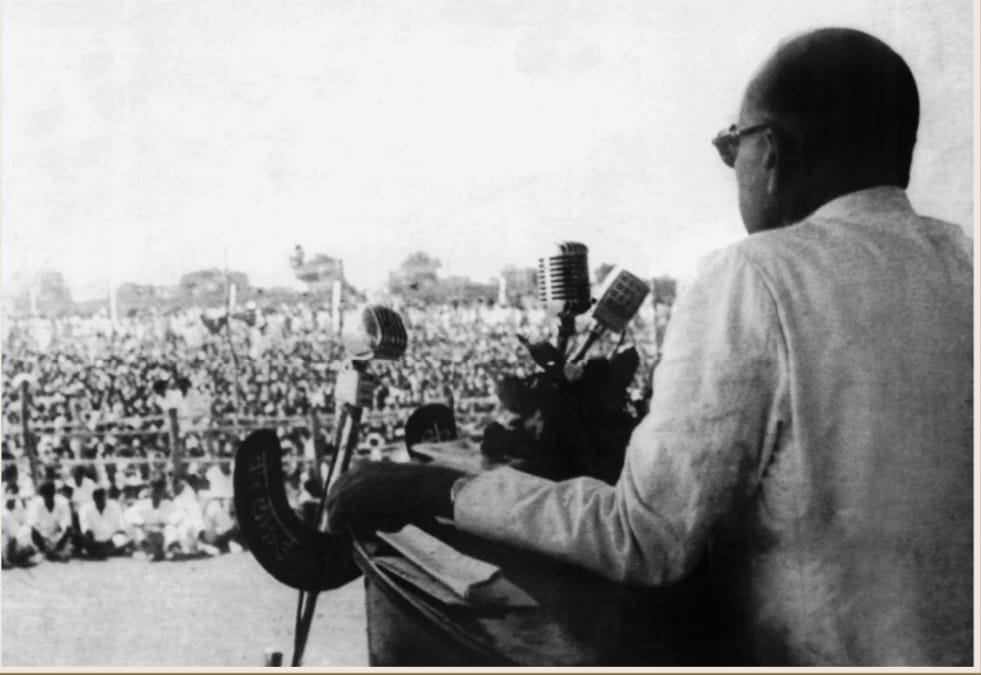

Ambedkar continued with his mission of reminding the people of their duties and rights and making them aware of the law. On 22 December 1952, he inaugurated the Pune district law library and gave a lecture on “Essential conditions for successful democratic functioning” to the members of the Pune Bar Association. This speech was widely discussed and debated in newspapers and magazines for many days. In his speech, he said that for the success of a democratic setup, it was essential that there was no social inequality and were no oppressed classes; the majority community should not hold sway over the minorities and there should be a powerful opposition for pointing out the mistakes of the government; all should be equal in the eyes of the law and the administration; and Constitutional morality should be adhered to and the social morality inherent in democracy should be followed. He said that there should be public goodwill and even revolutionary changes should be possible without a bloodbath. Barring exceptions, no party’s government in India has tried to follow these tenets.

As a member of the Bombay Legislative Assembly, as a Labour Member of Viceroy’s council and as a Rajya Sabha member, Ambedkar always had the concerns of the last man in the last row of society uppermost in his mind. He was consistently thinking about ways and means of strengthening the nation, ensuring its progress and uniting it. For instance, during the debate on the Constitution of a separate Karnataka state in Bombay Legislative Council, he insisted that national interest should get precedence over all other interests. His speech contained a clear delineation of the path towards building a prosperous nation. He said: “Personally myself I say openly that I do not believe that there is any place in this country for any particular culture, whether it is Hindu culture, or a Muhammadan culture, or a Kanarese culture or a Gujarati culture. There are things we cannot deny, but they are not to be cultivated as advantages, they are to be treated as disadvantages as something which divides our loyalty and takes away from us our common goal. That common goal is the building up of a feeling that we are all Indians. I do not like what some people say, that we are Indians first and Hindus afterwards or Muslims afterwards. I am not satisfied with that; I frankly say that I am not satisfied with that. I do not want that our loyalty as Indians should be in the slightest way affected by any competitive loyalty whether that loyalty arises out of our religion, out of our culture or out of our language. I want all people to be Indian first, Indian last and nothing else but Indians”. (Bombay Legislature, 1938).

He wanted Indians to have a shared identity, rising above the divisions of religion, class, caste and high or low culture – “a feeling that we are all Indians”. He was constantly on the lookout for ways to end inequality and usher in equality. He did not believe that the brahmanical Hindu religion – which was divided into castes and determined a person’s destiny on the basis of their birth – was amenable to any major reform. That was why he wanted leave the Hindu fold and associate himself with an ideology/religion that was free from dogma, rituals and inertia, a religion that could make humans the best creation of nature, a religion that aided in the progress of men and nation, a religion that was based on the universal values of justice, liberty, equality and fraternity and a religion that did not thrust laws and norms of behaviour on the people.

He led the biggest religious conversion (Dhamma Parivartan) in human history (Five lakh people embraced Buddhism on 14 October 1956, another five lakhs on Parinirvan and an estimated 16-17 lakhs subsequently). Before taking this momentous decision, he did an indepth study of all the religions of the world and was drawn towards Buddhism. But he did not accept Buddhism as it is. He was well aware of the rampant corruption in Buddhist sanghas and of the division of Buddhists into Hinyana, Mahayana, Bajrayana, etc. At the Dhamma Parivartan ceremony, Ambedkar took 22 oaths that he himself had written. These oaths were not shackles, they were not proscriptions. They were the way to salvation. They were about curiosity, progressiveness and emancipation. He called this way “Navayana”, that is a new vehicle for living one’s life. He envisaged a free-thinking individual who was free from all kinds of restrictions and bindings – a man who is not guided by blind faith or belief but who takes rational decisions on the basis of his own reasoning.

Conclusion

When Ambedkar was the principal of the law college, he used to say half in jest, “I will become a judge one day.” Of course, he had both the opportunity and the capability to become a judge. But had he confined himself to the bench, he would not have been able to bring about the social, political and economic changes that he has now been credited with. He did not become a judge but he did establish a democratic system imbued with the values of justice and equality. He built a system in which any capable person could become a judge. It was because of his scholarship and abilities that he was chosen to head the drafting committee of the Constituent Assembly. It was his juristic brilliance that made him the builder of the Constitution of India – one of the most diverse regions of the world. He accomplished the task entrusted to him with remarkable success and wrote a Constitution that freed the oppressed and suppressed, including Dalits, Tribals, Backwards, women, minorities and workers from their shackles. The laws formulated by him were not meant to limit but to remove all limitations and open the doors to true liberty and emancipation. For him, his identity as an Indian was supreme. He fought all his life for freeing men from the bondage of other men.

Dr Ambedkar was exceptionally successful in carrying forward his transformational and emancipatory mission. He ensured that the antiquated and obscurantist laws of the land were abandoned. Instead of them, he laid down objective laws aimed at national welfare and had them implemented. He could do this because of his deep juridicial knowledge and understanding. Attempts were made to belittle his contribution and his rich legacy through appropriation, manipulation and wrong interpretation. There were attempts to constrict Ambedkar’s humanistic, emancipatory and socialist democratic values based on the lofty ideal of equality. But we must recall the rich legacy of the knowledge and wisdom of Ambedkar – who was not an individual but an institution. Ambedkar had written extensively on economics, history, politics, sociology, education, religion, constitutional law and rights. His philosophy is not only relevant for India but also for the world.

References

- Omvedt, G. (2005). Ambedkar: Prabuddh Bharat Ki Or, trans Purnachand Tandon. Delhi: Penguin Books.

- Kashyap, O.P. ed (seventh edition, 2014), Babasaheb Dr Ambedkar Sampurna Vangmay (Volume 18), Delhi: Ambedkar Prathisthan, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India.

- Keer, D. (2016), Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Jeevan Charit, trans Gajanan Survey, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan.

- Kuber, W.N. (2013), Bhimrao Ambedkar, Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India.

- Moon, V. (2014), Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, trans Prashant Pandey, Delhi: National Book Trust

- Dhoke, V. (2015), Dr Ambedkar Ke Patra, Delhi: Gautam Book Centre

- Shashi, S. S. ed (Eighth edition 2014), Prathak Karnatak Prant Ka Gathan, in Babasaheb Dr Ambedkar Sampoorna Vangmay (Volume 3), Delhi: Ambedkar Prathisthan, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India.

- Constitution of India. Retrieved on 25 April 2017 from https://india.gov.in/my-government/constitution-india/constitution-india-full-text

- Dayal, K. (2013, Reprint), Famous Lawyers of Freedom Struggle and Trials of Freedom Fighters, Delhi: Universal Law Publishing Co Pvt Ltd.

- Gaikwad, V. B. (2012), Court Cases Argued by Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, Thane: Vaibhav Prakashan.

- Jaffrelot, C. (2005), Dr. Ambedkar and Untouchability: Analysing and Fighting Caste, Delhi: Permanent Black.

- Jatava D. R. (1993), ‘Ambedkar and Manu’, in Grover, Verinder, B. R. Ambedkar – Political Thinkers of Modern India-16. New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications.

- Johannes, Q. (2011), ‘Organised Rationalism in 20th-Century India’, Chapter 8 in Disenchanting India: Organized Rationalism and Criticism of Religion in India, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Levy, H. L. (Nov 1968-Feb 1969), ‘Lawyer-Scholars, Lawyer-Politicians and the Hindu Code Bill, 1921-1956’ in Law & Society Review, 3(2/3), 303-316.

- Mankar, V. (2013), Life and the Greatest Humanitarian Revolutionary Movement of Dr B. R. Ambedkar – A Chronology, Nagpur: Blue World Series.

- Mankar, V. (2016), Dr B. R. Ambedkar and An Intellectual Biography of Ideas, Enlightenment, Life and Liberation Work, Nagpur: Blue World Series.

- Manu, Olivelle, P, & Olivelle, S (2005), ‘The law for the king’ Chapter 7 in Manu’s Code of Law: A Critical Edition and Translation of the Mānava-Dharmaśāstra, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Moon, V. (2014), ‘Ranade, Gandhi and Jinnah’ in Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol 1, New Delhi: Dr Ambedkar Foundation, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Government of India.

- Moon, V. (2014), ‘Annihilation of Caste’ in Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol 1, New Delhi: Dr Ambedkar Foundation, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Government of India.

- Moon, V. (2014). ‘Statement by Dr B. R. Ambedkar in Parliament explaining his resignation from the Cabinet’, Annexure I in Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol 14 (Part Two), New Delhi: Dr Ambedkar Foundation, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Government of India.

- Moon, V. (2014), ‘Thoughts on the reform of legal education in the Bombay Presidency’ in Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches Vol 17 (Part Two), New Delhi: Dr Ambedkar Foundation, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Government of India.

- Moon, V. (2014). ‘Conditions precedent for the successful working of Democracy’ in Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches Vol 17 (Part Three), New Delhi: Dr Ambedkar Foundation, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Government of India.

- Nalwade, V, N. (1989), ‘Non-Brahman Movement’, Chapter III in Life and Career of Keshavrao Jedhe, Shivaji University, Kolhapur. (Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/10603/138403).

- Omvedt, G. (2003), ‘Navayana Buddhism and the Modern Age’, Chapter 8 in Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and Caste, New Delhi: Sage Publications India Pvt Ltd.

- Sharma, S. (2002), ‘Early Developments of Legal Profession’, Chapter 3 in Women Lawyers Practising at Delhi Courts: A Sociological Study (Retrieved From: http://hdl.handle.net/10603/29299).

- Tikekar, A. (2011), ‘As Bright As Ever’, in The Cloister’s Pale: A Biography of the University of Mumbai. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan

- Zelliot, E. (1969-70), The Religious Conversion Movement, 1935-1956’, Chapter IV in Dr Ambedkar and The Mahar Movement. (doctoral thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania, USA.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, literature, culture and politics. Next on the publication schedule is a book on Dr Ambedkar’s multifaceted personality. To book a copy in advance, contact The Marginalised Prakashan, IGNOU Road, Delhi. Mobile: +919968527911.

For more information on Forward Press Books, write to us: info@forwardmagazine.in