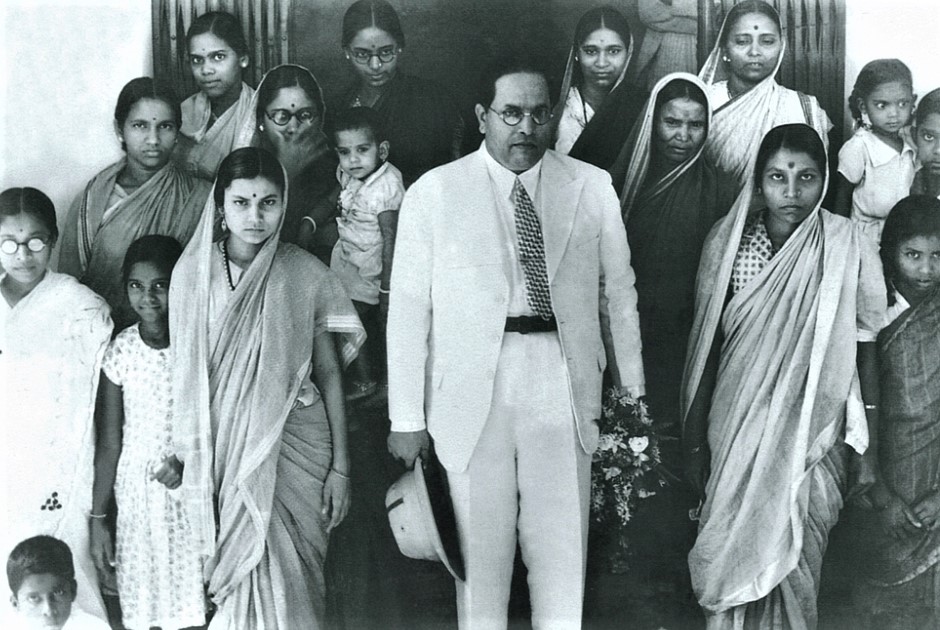

Even 60 years after the demise of the great Dalit emancipator and Indian constitutional architect, Dr B. R. Ambedkar, his thoughts continue to have a deep impact on Indian society. He became the first law minister of India and played a major role in the making of Indian Constitution. The hardships that Ambedkar underwent throughout his life to achieve all that he did made him think about overhauling the principles that underlie the concept of justice in Indian society. The existing model of justice in Indian political thought was divisive – for example, the hierarchical order within the caste system. The preamble of Indian Constitution that Ambedkar drafted proposes to secure to all citizens justice – social, economic and political. These form the core of the Ambedkarite concept of justice.

The concept of ‘justice’

Justice is considered the most important value in political philosophy. There are different schools of thought on justice depending on whether they are ancient or modern, or whether they have originated in the East or the West. Greek thoughts on justice predated all others and are predominant too.

The ancient Greek political thought identified justice as a virtue, thus incorporating it into moral philosophy. The king or the State was portrayed as divine and considered the abode of justice. Plato and Aristotle identified “good society” as “just society” (Heywood 2000). Plato considered justice as the virtue of the wise and according to him no ideal State was possible without justice (Srivastava 1997). Aristotle equated justice with fairness and equity. Justice in Indian political thought can be traced to the Manusmriti and Arthasashtra of Manu and Kautilya, respectively. Here, too, justice was treated as a virtue, or dharma.

Laws are formulated as a mechanism for the fulfilment of a just society. Justice became equated with the proper implementation or enforcement of law. However, the law is only one of the dimensions of justice, the others being right and need. The proponents of natural rights like Robert Nozick go for a minimum State. In utilitarianism, the criterion determining justice is “maximum happiness to the maximum number of people”. The greatest turning point came with John Rawls’ theory of justice, which proposes how justice deals with the condition of inequality in the society.

Rawls’ concept of justice seeks equal consideration of all people. Even Plato had considered inequality when he noted that “democracy distributes an odd sort of equality to equals and unequals” (Srivastava 1997). Rawls’ idea of “justice as fairness” is both political and moral in conception, formulated keeping in mind the basic structure of modern constitutional democracy (Rawls 1997). Ambedkar’s theory of justice resembles Rawls’ in that it seeks to establish a just and fair society considering the inequality within society. It captured Rawls’ “justice as fairness”.

Ambedkar grew up and strove for excellence as a lawyer and economist in a system where social inequality prevailed, leading him to realize that political and economic justice would remain elusive without first attaining social justice. His was a quest for radical social revolution as a prerequisite of all other kinds of transformations – including political and economic.

Valerian Rodrigues identifies Ambedkar as a political philosopher in his essay “Ambedkar as a Political Philosopher”, and lists out the concerns of justice, liberty, equality, community, democracy, authority, legitimacy and recognition as his lifelong pursuits (Rodrigues 2017). His idea of social justice is inclusive of political and economic justice too. Ambedkar sought prioritization of the social upliftment of the least advantaged, including Dalits, minorities, women and workers. He believed that the caste system, communalism, patriarchy and industrial exploitation of workers created inequality and stood in the way of a just society. Due to the rigidity and persistence of these sources of inequality, Ambedkar prescribed active role of the state in the emancipation of the unequals. The cornerstone of Ambedkarite justice is liberty, equality and fraternity.

Caste system

Ambedkar vehemently opposed the caste system and his Annihilation of Caste is his most renowned work on the subject. Each caste has its own hereditary occupation and members of a particular caste are not allowed to choose the occupation of another caste. Inter-marriage and inter-dining with other castes is restricted. The Brahmins are entitled to learn, teach and perform temple rituals. In this respect, the caste system has strong backing of the religious scriptures, which led Ambedkar to say, “it is not possible to break caste without annihilating the religious notions on which the caste system is founded”. (Ambedkar 2014)

The caste system clearly violates the principles of liberty, equality and fraternity. It takes away an individual’s right to choose an occupation for himself. The loyalty of an individual is towards the caste in which he/she is born and there is no place for compassion and love within the caste system. People are not treated impartially within the caste system. Hence, Ambedkar suggested reservation as a measure for social emancipation.

Religion

Ambedkar was not against religion. He defends religion by quoting Edmund Burke, who said that true religion is the foundation of society, the basis on which all true civil government rests. However, Ambedkar did not consider Hinduism as a religion because it was based on the caste system, which violated the triad of justice – liberty, equality and fraternity. Ambedkar referred to Hinduism as mere guidelines or a plethora of commands and strictures (rules, not principles) given to followers.

The basis of a Hindu society is its divisiveness. How can it tolerate other religions when it cannot tolerate Hindus belonging to another caste? The Hindu community appears united only when communal violence with either of the two other prominent religious communities flares up. Ambedkar was deeply concerned about the rights of minorities. He expressed his views on problems faced by minorities in the memoranda that he submitted to the Simon commission and at the Round Table Conferences (Singh 1997). He was aware of the threat facing the minorities within a majority-dominated area, and thus supported the demands made by minorities for proper representation in the legislature, executive and the public services.

Gender

While attacking the caste system, Ambedkar never forgot to mention the denial of rights to women within the Hindu social system. He condemned sati, child marriage and argued for widow remarriage in accordance with his vision of restructuring the Hindu family system. With the Hindu Code Bill, he proposed granting of the rights to the property of the deceased to both their male and female progeny.

On 18 July 1927, while addressing a meeting of more than 3,000 women of Depressed Classes, Ambedkar said that the progress of a community can be measured by the progress the women have made (Ramaiah, 2017). He advocated the girlchild’s education, ensuring the dignity of women with regard to menstruation, the right of women to act as priests, maternity benefits for women, divorce maintenance, etc. Ambedkar thus felt strongly about the discrimination against women in a patriarchal society and called for gender justice.

Labour

Ambedkar was also part of struggles to better the lot of workers. He formed the Independent Labour party in 1936 for the welfare of workers. He introduced an amendment bill in 1944 that mandated paid leave to workers who serve at a factory continuously for a certain period. Ambedkar talked about the justice that the labourers need to get from their owners through minimum wages, good working conditions, reducing working period, etc. Ambedkar gave India the gist of labour rights.

Ambedkar saw the caste system not only as a division of labour but also a division of labourers. The caste system restricts a person’s choice of profession and denigrates the work performed by lower strata. Ambedkar also considered, along with the caste system, capitalism as a source of exploitation of labourers. Ambedkar considered Brahmanism and capitalism as the twin enemies of his movement (Das 2017).

Ambedkar viewed caste system as the chief factor of imbalance with respect to justice in Indian society. Any kind of inequality created in society can create this imbalance in justice. It violates the core principles – liberty, equality and fraternity – that Ambedkar put forward as the core of the concept of justice. The rights of Dalits, women, minorities and labourers are violated within the caste system. Ambedkar’s concept of distributive justice was based on a casteless society (Narayan Das, 2017). His concept of justice was egalitarian in the sense that he wanted all people to be treated as equals, unlike the caste system which treats people based on their assigned social status; the distribution of all social and economic goods is based on this hierarchical order.

Egalitarian justice

Ambedkar’s vision of justice was of all individuals being treated as equals in terms of worth and social status. Ambedkar outrightly rejected the agents of social inequality and exploitation. He believed liberty, equality and fraternity need to be maintained in a system to secure egalitarian justice. The caste system, which violates three basic tenets, was the main obstacle to this idea of justice taking root in society.

The laws, to Ambedkar, were to be such that it guaranteed the rights of the least advantaged. The Hindu Code Bill, which Ambedkar introduced in Parliament, ran counter to the brahmanical law, the code of conduct within the Hindu family. Sons and daughters were to have equal rights to their father’s property and the bill had revolutionary provisions regarding monogamy and divorce, favouring women (EPW 1949).

Ambedkar differed from the Indian National Congress in their approach to attaining freedom and he stood apart from the freedom struggle. He envisioned social justice as a prerequisite for political justice. He introduced an alternative dimension to the concept of equality and revolution in attaining Justice. He advocated “inequality” that benefited marginalized sections. That is the reason he supported the idea of separate electorate, which he later was forced to abandon due to Gandhi’s protests. He drafted provisions for reservations, which were meant for gradual development in the social and economic condition of the disadvantaged. Ambedkar dreamt about a social revolution as a primary step.

Ambedkar had a diverse perspective on the concept of revolution in the pursuit of justice. It did not bear the same meaning as was in vogue, particularly in Marxist circles (Das 2017). The revolution that Ambedkar envisaged did not involve bloodshed. His revolution would be free from insurrections. He preferred social revolution to political revolution. He believed in democracy and considered the Hindu social order an anathema to society. Ambedkar propounded the idea of restructuring Hindu society. He listed out steps to be adopted in restructuring the Hindu social order, such as the abolition of priesthood. He also called out for the destruction of the sanctity of religious scriptures like the Manusmriti.

Ambedkar’s vision of egalitarian justice allowed for unequal treatment to benefit the least advantaged in society – which resembles John Rawls’ theory of “justice as fairness”. He recognized rights and laws as key to justice – rights determine the concept of justice and law of the land protects the rights. On the other hand, the caste system, communalism, patriarchy and exploitation of workers, were to him, major impediments for the establishment of a just society. Ambedkar insisted that social restructuring of society precede an economic and political revamp because he believed that social justice would eventually lead to political and economic justice. Our society has yet to embrace his vision of justice as it refuses to let go of the caste and gender hierarchies.

References

- Ambedkar, B. R. (2014). Annihilation of Caste: The Annotted Critical Edition. New Delhi: Navayana Publishing House.

- Das, Narayan (2017). Dr B.R Ambedkar and Women’s Empowerment. New Delhi: Centrum Press.

- Das, Narayan (2017). Thoughts of Dr Bhim Rao Ambedkar. New Delhi: Centrum Press.

- Heywood, Andrew (2008). Key Concepts in Politics. New York, NY: Palgrave.

- Massey, James (2017). ‘Dr Ambedkar’s Vision of a Just Society’. In Avatti Ramaiah (ed), Contemporary Relevance of Ambedkar’s Thoughts. Jaipur: Rawat Publications.

- Rawls, John (1997). ‘Justice as Fairness: Political Not Metaphysical’. In Stephen Eric Bronner (ed), Twentieth Century Political Theory – a Reader (Second Edition). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Rodrigues, Valerian (2017). ‘Ambedkar as a Political Philosopher’, in Economic and Political Weekly, LII (15), 101-107.

- Singh, Surendra (1997). ‘Dr Ambedkar’s Contribution to Social Justice’. In Mohammad Shabbir (ed), B.R. Ambedkar: Study in Law and Society. Jaipur: Rawat Publications.

- Srivastava, S.P (1997). ‘Toward Explaining the Concept of Social Justice’. In Mohammad Shabbir (ed), B.R Ambedkar: Study in Law and Society. Jaipur: Rawat Publications.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, literature, culture and politics. Next on the publication schedule is a book on Dr Ambedkar’s multifaceted personality. To book a copy in advance, contact The Marginalised Prakashan, IGNOU Road, Delhi. Mobile: +919968527911.

For more information on Forward Press Books, write to us: info@forwardmagazine.in