Bhimrao Ambedkar’s final gift to the world, as well as to his cause for “untouchable” rights, was his posthumously published Buddhist gospel, The Buddha and His Dhamma (1957).[1] One of the hallmarks of this work – and one of the reasons some orthodox Buddhists reacted negatively to it – was his belief that Buddhism must be reconstructed to meet the needs of the present. For Ambedkar, this meant writing a religious-philosophical outlook out of various Buddhist texts that could address the needs of his fellow Untouchables in India; given his publication of this work in English in its initial edition, he also clearly had global aspirations for his new vision of the Buddha’s teachings.[2] Ambedkar was invested in making a religion that counted in the lived experience of practitioners, a point that is evident in his reconstruction in this book of ahimsa as love instead of as non-harm. In talking about the Buddha’s view on violence, Ambedkar asks “whether His Ahimsa was absolute in its obligation or only relative. Was it only a principle? Or was it a rule?”[3] Ambedkar answers this question by noting that the Buddha’s teaching indicates that one is to “‘Love all so that you may not wish to kill any.’ This is a positive way of stating the principle of Ahimsa … the doctrine of Ahimsa does not say ‘Kill not. It says love all.’”[4] This reading of a central Buddhist doctrine leaves much leeway to the agent for application, interpretation, and adaptation to their situation. Ambedkar does not ignore the tradition of Buddhist texts and teachings to get to this point, but he engages them in a creative and reconstructive way.

How does he get to this reconstruction of Buddhism? As with any great thinker, Ambedkar’s thought must be analyzed as a changing, fluid, and developing whole. As I have argued elsewhere, part of the key in seeing what Ambedkar is doing in his reconstruction of Buddhism comes when one recognizes him as a pragmatist thinker of a certain type. It is well-known that he received much of his education at Columbia University in 1913-1916, and that this time was very formative. It is also known that John Dewey, the American pragmatist philosopher, was one of his most influential teachers. Eleanor Zelliot argues that “John Dewey seems to have had the greatest influence on Ambedkar.”[5] Arun Mukherjee emphasizes the centrality of Dewey’s pragmatism to Ambedkar’s work in the 1930s, and warns scholars against engaging it “in isolation, without paying attention to his dialogue with Dewey.”[6] K. N. Kadam reports that “Dr. Ambedkar took down every word uttered by his great teacher [Dewey] in the course of his lectures; and it seems that Ambedkar used to tell his friends that, if unfortunately Dewey died of a sudden, ‘I could reproduce every lecture verbatim.’”[7] Beyond these observations, the continuing challenge is to fill out what specifically Ambedkar learnt from his great teacher, John Dewey.

How do we go about answering this question? One path is to trace how Dewey’s ideas and words end up in Ambedkar’s writings and speeches. Some scholars have tried this tact with useful results.[8] Some of my own work has focused on finding the classroom sources of Ambedkar’s pragmatism in the form of the lecture notes from the Columbia University courses taken with Dewey.[9] All of these projects tend to start with Ambedkar’s published works and proceed backwards towards his pragmatist sources. There is a second path that remains open, one that relies heavily on the texts and sources that Ambedkar engaged before he wrote or spoke. This is the approach that searches for what Ambedkar engaged with in his initial brushes with pragmatism, driven by the idea that this information will be helpful as we proceed forward to his later works. This approach follows the lead of Christopher Queen, whose work has built upon the idea that the sources used and texts engaged by a thinker such as Ambedkar can be used to outline what that thinker found as important or significant in those texts. Queen uses this approach to great effect in charting what Ambedkar’s annotations in his personal books tell us about the ideas that influenced him during his education.[10] Elsewhere, I have exploited this tactic in comprehensively reconstructing Ambedkar’s form of pragmatism from his marks and emphases in his personal copy of Dewey’s Democracy and Education.[11] I will follow this approach in exploring the pragmatist background that informs and shapes Ambedkar’s reconstructive quest for social justice in India. One of his techniques in this quest was to reconstruct Buddhism as a religion of principle. The very distinction between rule and principle in the previously discussed passage from The Buddha and His Dhamma offers us a clue – this distinction comes from a Deweyan text, one that Ambedkar had in his possession upon his death. This work is the 1908 edition of a book authored by John Dewey and James Hayden Tufts, Ethics.[12] How did this Deweyan work influence Ambedkar’s view of religion, reconstruction, and social justice?

The mystery of Ambedkar’s copy of Ethics

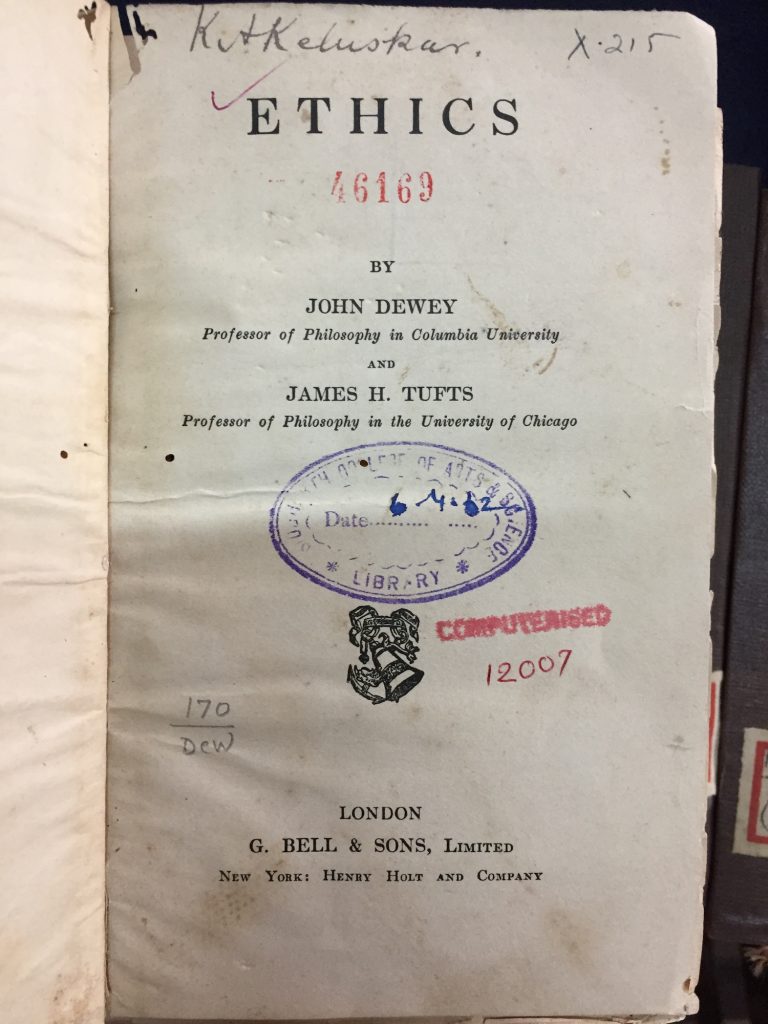

Before we can examine the influence of Dewey and Tufts’ Ethics on Ambedkar, we must reflect on the mystery surrounding Ambedkar’s copy of the book in question. This text is currently preserved in the archive of Ambedkar’s personal books stored at Siddharth College. But when did he get hold of this work? Unlike his copies of other books by Dewey obtained during his student years at Columbia or in London, there is no notation of the date and location of acquisition.[13] There is a mystery here that has yet to be unravelled by scholars of Ambedkar’s life and thought. The book itself possesses a copyright date of 1908, but further examination of its title page shows that it was the British edition, most likely published as a re-issue in late 1910.[14] How did he get this book? Another clue becomes apparent on the title page – in handwriting at the top is “K.A. Keluskar”. This in all likelihood refers to Krishna Arjun Keluskar, a Maharashtra-based reformer and teacher at Wilson High School in Bombay who befriended young Ambedkar while he was studying at Elphinstone High School. Christopher Queen has also noticed this annotation, and infers that this means that Keluskar gave Ambedkar the book.[15] No other evidence survives that I have been able to locate that sheds any more light on the history of this text, so this guess is as good as any. Looking closely at the handwriting,  one muses more on its creation. It could be from Ambedkar’s own hand, but the shape of the initial “A” doesn’t seem to match with the usual “A” in “Ambedkar” as he signed it elsewhere, nor with the cursive capital “A” typically found in his letters. Short of clear evidence to the contrary, the best inference must be that Keluskar gave Ambedkar this book; a slightly less likely, but still plausible, hypothesis was that Ambedkar marked this book himself to note that it hailed from Keluskar’s library.

one muses more on its creation. It could be from Ambedkar’s own hand, but the shape of the initial “A” doesn’t seem to match with the usual “A” in “Ambedkar” as he signed it elsewhere, nor with the cursive capital “A” typically found in his letters. Short of clear evidence to the contrary, the best inference must be that Keluskar gave Ambedkar this book; a slightly less likely, but still plausible, hypothesis was that Ambedkar marked this book himself to note that it hailed from Keluskar’s library.

This conjecture about how Ambedkar gained this book does not answer the other pressing question of when he came into possession of it. We know that Keluskar took a liking to Ambedkar early in the latter’s education, first finding the young Bhimrao in a public garden fleeing schoolyard bullying. It seems likely that this initial contact occurred around 1904 or 1905.[16] Keluskar took Ambedkar under his wing, giving him access to his private library and often lending him books. Keluskar was also a central figure in Ambedkar’s graduation celebration in 1907, giving him a copy of his book, Life of Gautama Buddha, in recognition of the young Ambedkar’s accomplishment.[17] Keluskar was also instrumental in getting Ambedkar funding for his subsequent education at Elphinstone College in Bombay and eventually at Columbia University during 1913-1916 from the Gaikwad of Baroda.[18] Thus, we are left with a set of tantalizing details: Keluskar was an avid supporter who often lent or gifted books to Ambedkar, he was concerned about Ambedkar’s further education in the West, and tried hard to help the young man in any way that he could. Might he have given young Ambedkar this pragmatist book, published from a British press at the end of 1910, in the year or so before the young man left for Columbia University? If so, it would mean that Ambedkar to some extent knew of his great teacher John Dewey before first stumbling into his philosophy classes in 1914 while studying economics and political science at Columbia.

This is an intriguing possibility, but the timing weighs against its likelihood. First of all, there are no personal signatures or locations of acquisition noted in this book like his other books from the educational period 1913-1917 that I was able to peruse at Siddhartha College. Second, there were many more years for Keluskar’s gifting of this book after Ambedkar returned from his studies abroad – before his death in 1934, he remained in contact with Ambedkar in the 1920s and 1930s.[19] Perhaps the biggest clue comes in the traceable influence of Ethics on Ambedkar’s works. As we shall see, the internal contents of Ethics privileges normative analysis of groups, customs, and individual reflective morality – topics that we do not see as explicitly evident in his early proclamations in “Castes in India” (read in 1916 and published in 1917) and his 1919 testimony before the Southborough Committee.[20] Unlike his copy of Democracy and Education (procured in 1917), one does not see obvious references to or echoes of Ethics until the 1930s, most prominently in Ambedkar’s magisterial “Annihilation of Caste” from 1936.[21] If we had to place a date on the acquisition of Ethics from Keluskar, I would hypothesize that it was in the late 1920s or early 1930s. This avoids the hectic period of Ambedkar’s returns to Europe in the early 1920s. If this is correct, it means that Ambedkar most likely received this book at the height of his projects as an on-the-ground activist, seeking temple entry and water access and concessions from the British for his fellow Untouchables. One starts to see Ambedkar talk some about customs and using the Deweyan idea of reflective morality in a letter that he wrote to A. V. Thakkar on his way to London in November 1932.[22] Even in this letter, however, one sees Ambedkar talking more in the language of Democracy and Education – a text we know he possessed since 1917 – than in the ideas of Ethics (for instance, he talks of social intercourse and contact between groups, key notions in Dewey’s Democracy and Education).[23] This might serve as some indication that Ambedkar only began processing the contents of Ethics in the early 1930s; this is compatible with acquisition dates falling both in the late 1920s and the early 1930s. As we will see, Ambedkar clearly drew upon the pragmatist ideas of Ethics by the time of his important blow against Hinduism, his 1936 “Annihilation of Caste”.

Charting the influence of the 1908 Ethics on Ambedkar

Understanding Dr Ambedkar’s sources are an important part of understanding what this scholar used to construct his philosophy and strategies of activism. What did Ambedkar take from the 1908 Ethics? What themes struck him as worth noting and remembering, and possibly using later in his activism? It seems difficult to answer these questions, now that Ambedkar is gone. But his beloved books and legacy of activism remain, leaving us a path forward. Following the method of starting with Ambedkar’s textual highlights and annotations to his copy of Ethics, we can start to discern a novel pattern of an anthropologically grounded view of critique that paves the way for his criticism of the caste system as well as his reconstruction of Buddhism. Here I will deal with two main themes that arise in turn from his marking of this text, but much more can still be said about Ambedkar’s relation to pragmatism.

Understanding Dr Ambedkar’s sources are an important part of understanding what this scholar used to construct his philosophy and strategies of activism. What did Ambedkar take from the 1908 Ethics? What themes struck him as worth noting and remembering, and possibly using later in his activism? It seems difficult to answer these questions, now that Ambedkar is gone. But his beloved books and legacy of activism remain, leaving us a path forward. Following the method of starting with Ambedkar’s textual highlights and annotations to his copy of Ethics, we can start to discern a novel pattern of an anthropologically grounded view of critique that paves the way for his criticism of the caste system as well as his reconstruction of Buddhism. Here I will deal with two main themes that arise in turn from his marking of this text, but much more can still be said about Ambedkar’s relation to pragmatism.

Let us start by examining the text itself. One notices that his copy of Ethics is heavily marked, in all the styles of emphasis that one can find in his books: blue, red, and grey pencil, along with lines under the text and next to passages. One also finds his characteristic check-marks in the margin, usually in grey pencil. By my count, there are 110 pages with marks on them. The book was divided by Dewey and Tufts into three main parts: “The Beginnings and Growth of Morality”, “Theory of the Moral Life”, and “The World of Action”. According to the preface, Tufts authored the entire first section and all but the first two chapters of the third section; Dewey authored the entire second part and the first two chapters of the third part. Both contributed “suggestions and criticisms to the work of the other in sufficient degree to make the book throughout a joint work”.[24] Ambedkar heavily (and evenly) annotated Tufts’ first section on the development of morality, and added sporadic annotations throughout Dewey’s more theoretical second part. The only marks by Ambedkar in the final section occur in the two chapters contributed by Dewey, even though the final chapters deal with topics in economics and morality.[25] Examining the major themes that Ambedkar engaged with will highlight the source of crucial commitments in his philosophy of social justice.

From customary morality to reflective morality

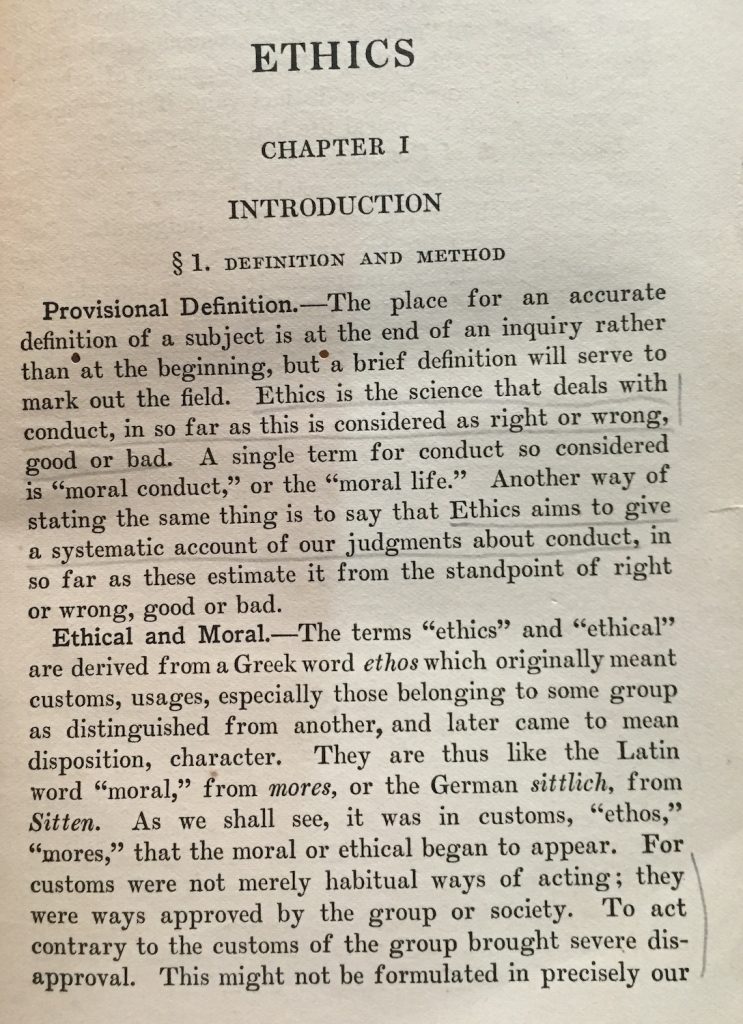

Ambedkar clearly knew of the importance of social groups, as he wrote on caste as early as 1916 in his essay, “Castes in India”. But one sees from his engagement with specific parts of Ethics that his anthropological interest in familial and societal groups gains an added dimension by being connected to a moral project. This is vital, as it will be a unique theme that is not emphasized in Dewey’s sole-authored works that Ambedkar was exposed to at Columbia or in India. Ambedkar’s engagement with Ethics opens up Deweyan pragmatism filtered through the anthropological emphasis of Tufts’ contribution. From the very beginning of Ethics, we see Ambedkar highlighting (in grey pencil) the lines that “Ethics is the science that deals with conduct, in so far as this is considered as right or wrong, good or bad… Ethics aims to give a systematic account of our judgments about conduct.”[26] Ambedkar saw the normative aspect to morality, its focus on choice, justification and values. As he would underline in red pencil, ethics is about choice of values, but also of one’s self: “I am to ‘choose’ it [the good] and identify myself with it, rather than to control myself by it. It is an ‘ideal’.”[27] Thus, ethics was seen as choice of action, as well as of the sort of self that we create through that action.

Ambedkar clearly knew of the importance of social groups, as he wrote on caste as early as 1916 in his essay, “Castes in India”. But one sees from his engagement with specific parts of Ethics that his anthropological interest in familial and societal groups gains an added dimension by being connected to a moral project. This is vital, as it will be a unique theme that is not emphasized in Dewey’s sole-authored works that Ambedkar was exposed to at Columbia or in India. Ambedkar’s engagement with Ethics opens up Deweyan pragmatism filtered through the anthropological emphasis of Tufts’ contribution. From the very beginning of Ethics, we see Ambedkar highlighting (in grey pencil) the lines that “Ethics is the science that deals with conduct, in so far as this is considered as right or wrong, good or bad… Ethics aims to give a systematic account of our judgments about conduct.”[26] Ambedkar saw the normative aspect to morality, its focus on choice, justification and values. As he would underline in red pencil, ethics is about choice of values, but also of one’s self: “I am to ‘choose’ it [the good] and identify myself with it, rather than to control myself by it. It is an ‘ideal’.”[27] Thus, ethics was seen as choice of action, as well as of the sort of self that we create through that action.

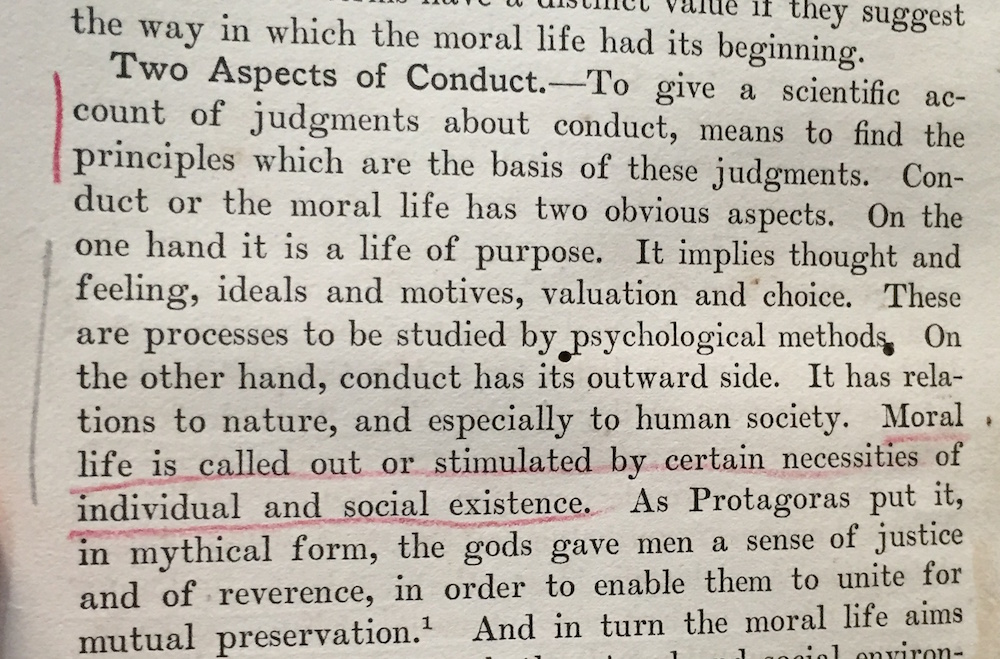

Tufts’ section quickly ensconced this normative choice of ideals (and self) within an empirical account of the development of ethics. Tufts analyzes the importance of kinship groups and religious units on the development of morality. Our groups shape our  actions and beliefs through their influence. This can and does change given development and moral progress. What is important for our present inquiry is the unique pattern that this explication takes in Ethics, a version of the Deweyan story of reconstruction that differs from his explanations elsewhere. Ambedkar highlights in red the three levels of conduct: “1. Conduct arising from instincts and fundamental needs … 2. Conduct regulated by standards of society … 3. Conduct regulated by a standard which is both social and rational, which is examined and criticized.”[28] The point that is made here is complex – societies form and shape their individual members, but this is not the end of the story of morality. Instead, individuals and groups strive to rise to the third level, one involving conscience and reflective consideration of why agents act in that way. The sociological second level is important for moral matters because it is related to habits, force and control; as Ambedkar underlines, “Inasmuch as the agencies by which the group controls its members are largely those of custom, the morality may be called also ‘customary morality’.”[29] Groups train their members to act in certain ways, forming and enforcing desired habits in those individuals through shared experience.

actions and beliefs through their influence. This can and does change given development and moral progress. What is important for our present inquiry is the unique pattern that this explication takes in Ethics, a version of the Deweyan story of reconstruction that differs from his explanations elsewhere. Ambedkar highlights in red the three levels of conduct: “1. Conduct arising from instincts and fundamental needs … 2. Conduct regulated by standards of society … 3. Conduct regulated by a standard which is both social and rational, which is examined and criticized.”[28] The point that is made here is complex – societies form and shape their individual members, but this is not the end of the story of morality. Instead, individuals and groups strive to rise to the third level, one involving conscience and reflective consideration of why agents act in that way. The sociological second level is important for moral matters because it is related to habits, force and control; as Ambedkar underlines, “Inasmuch as the agencies by which the group controls its members are largely those of custom, the morality may be called also ‘customary morality’.”[29] Groups train their members to act in certain ways, forming and enforcing desired habits in those individuals through shared experience.

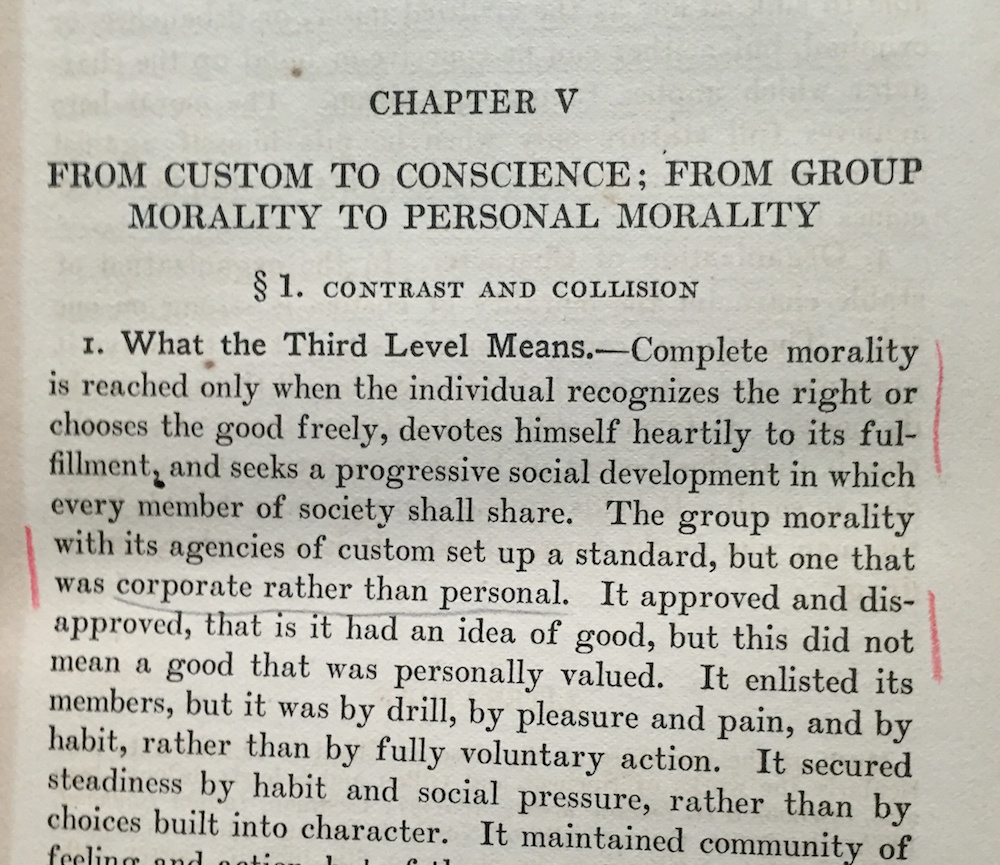

Ambedkar the reader continues to highlight this theme concerning the force of group customs at various places, but it is important to segue to the contrasting third level that intrigues Ambedkar: that of reflective morality. Ambedkar read and underlined the clearest exposition of this point in Ethics: “Complete morality is reached only when the individual recognizes the right or chooses the good freely, devotes himself heartily to its fulfilment, and seeks a progressive social development in which every member of society shall share.”[30] Habits and customs are forced and enforced by the group, according to this account, and are inherently conservative. They exist to maintain the group as it is, and typically as it was. Yet moral progress asks for more, according to the reading of Dewey and Tufts in the 1908 Ethics. Ambedkar notices Dewey’s emphasis in the second part of Ethics on the role of reason in moral progress. He underlines Dewey’s attempt to break down the progress toward morality to a very personal quest to reshape one’s self:

“Which shall he decide for, and why? The appeal is to himself; what does he really

think the desirable end? What makes the supreme appeal to him? What sort of an agent, of a person, shall he be? This is the question finally at stake in any genuinely moral situation: What shall the agent be? What sort of a character shall he assume? On its face, the question is what he shall do, shall he act for this or that end.”[31]

Here in Dewey’s section, we see the emphasis on morality shifting to the level of the individual. The agent has some role to play in the transition from a merely customary, group-based morality to a more reflective morality. The way they do this, of course, is through the capacity for reasoning through means and ends, a point that Ambedkar highlights in red pencil: “But the incompatibility of the ends forces the issue back into the question of the kinds of selfhood, of agency, involved in the respective ends.”[32] It is conflict among valued ends, perhaps driven by contrary habits, that calls for reasoning and reflection to assuage the situation. If this call is answered, reflective morality is instantiated.

Where do we start to see these themes appear in the works of Ambedkar? The earliest – and the clearest – employment of the idea that moral development is progression from customary morality toward reflective morality is in Ambedkar’s undelivered speech, “Annihilation of Caste”. Originally written as an address to the high-caste reformers of the Jat-Pat-Todak Mandal, scandal over its anti-Hindu message prevented it from being presented in public; Ambedkar eventually sold his printed versions of the address starting in 1936.[33] One sees in this text the same delineation of cultural groups by habit or custom – central terms in Dewey and Tufts’ Ethics. For instance, Ambedkar talks of the “similarity of habits and customs, beliefs and thoughts” among Hindus in India at various points in his address.[34] The primary habit or custom that Ambedkar believes defines Hinduism is a commitment to a graded system of castes. This custom is reinforced by age-old texts that provide rigid rules and procedures for caste Hindus to follow. All of this is consistent with the developmental model of customary morality in Ethics.

Similar to what he absorbed while reading Dewey and Tufts’ Ethics, Ambedkar in 1936 assumes the challenge of moral progress is to transition from a group based upon custom and habit to one based upon reflection. Thus, Ambedkar, using the concepts of reflective morality, criticizes the rigid system of caste that is derived from old and putatively inspired texts. He muses about the lack of criticism within the Hindu tradition concerning the institution of caste, and speculates that the shastras and holy texts “have taken care to see that no occasion is left to examine in a rational way the foundations of his belief in Caste and Varna.”[35] One sees the foundation of the rest of his critique from the basic progression assumed in Ethics. “Man’s life is generally habitual and unreflective,” Ambedkar argues, echoing Tufts’ portion of Ethics.[36] What is occluded by this mindless habitual basis to action formed by group customs? Echoing the line of argument in Ethics, Ambedkar indicates that “reflective thought, in the sense of active, persistent and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form or knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and further conclusions to which it tends, is quite rare and arises only in a situation which presents a dilemma – a crisis.”[37]

Whereas Dewey’s Democracy and Education gave Ambedkar a vocabulary for reconstruction, Ethics gave him the framework necessary to describe how groups enforce habitual patterns of activity, and what ideally ought to lie beyond such a state should the group be led to moral progress.[38] Hinduism, according to his “Annihilation of Caste” address, needed to suffer a crisis to jar it (and its individual members) towards the use of reflective thought. It is only then that the correction of harmful customs – namely, caste and the anti-social spirit it facilitates – could be meliorated. One can see the pragmatist mix of the social scientific study of caste and the normative urge to refine and meliorate a group’s morality by the end of his address, where he writes that “the Hindus must consider whether it is sufficient to take the placid view of the anthropologist that there is nothing to be said about the beliefs, habits, morals and outlooks on life, which obtain among the different peoples of the world except that they often differ; or whether it is not necessary to make an attempt to find out what kind of morality, beliefs, habits and outlook have worked best and have enabled those who possessed them to flourish, to go strong, to people the earth and to have dominion over it.”[39] By 1936, Ambedkar is convinced that we must understand caste and critique it, and texts such as the 1908 Ethics gave him the synthetic vocabulary of pragmatism as a means to fully enunciate this concern.

The role of the individual in moral progress

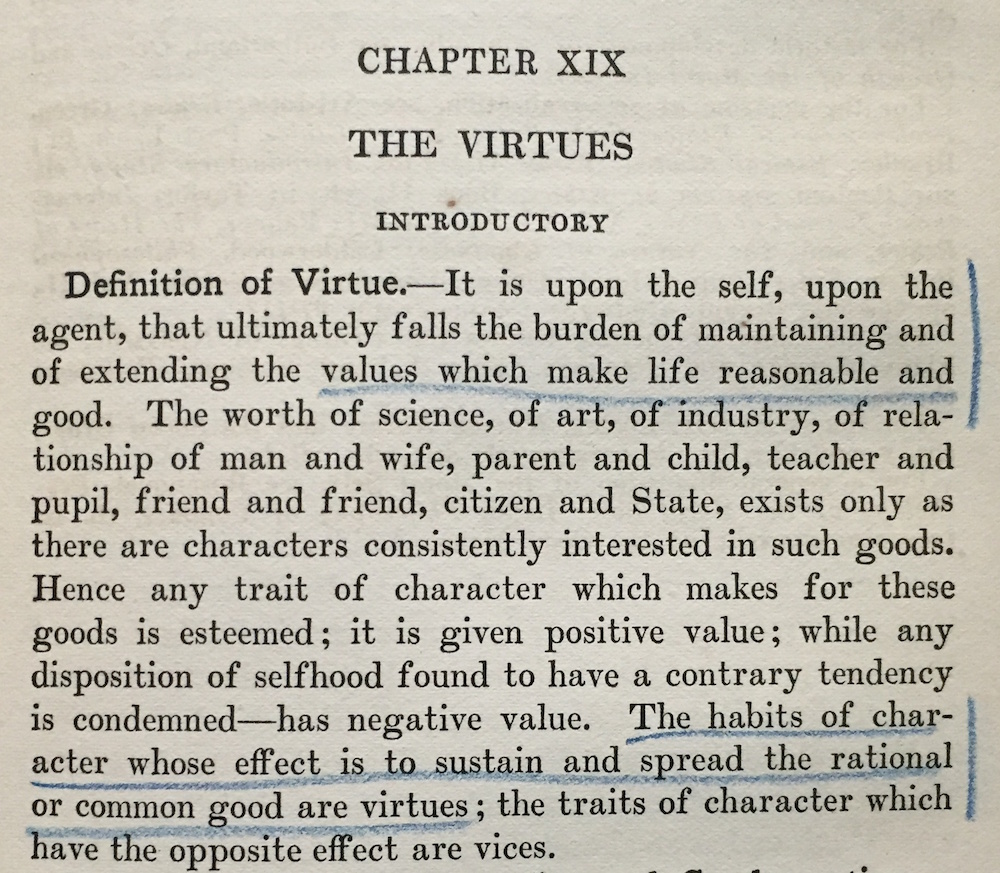

The second theme that Ambedkar has noted while reading Ethics concerns the role of the individual in moral progress. Whereas texts such as Democracy and Education feature individuals as the locus of a process of habit formation, the 1908 Ethics makes a point to foreground individual reflective thinking about the problematics of morality. As we saw in the previous section – and in portions of the “Annihilation of Caste” address – getting all individuals to reason and reflect on values and ends is a vital part of escaping custom-based group morality. But “reason” is no abstract capacity of the human mind; it is really shorthand for certain useful ways of thinking through concrete problems. What can be said about these more or less abstract guides to the range of specific actions? In Dewey’s portion of Ethics, we are introduced to an important distinction for Ambedkar’s pragmatism: the distinction between rules and principles. In part two, Dewey castigates set rules of past moral theories as unresponsive to the demands of the particular situations. Ambedkar highlights Dewey’s clearest statement of these two mental shortcuts to activity with a two grey marginal lines: “Rules are practical; they are habitual ways of doing things. But principles are intellectual; they are useful methods of judging things.”[40] Habits and customs are problematic because they are based in the past and unresponsive to any given present situation, but how can one rectify or improve these remnants from a group’s past experience? One cannot be without any habit or custom. It is through the application of principles, or “useful methods” of judgment, that our activity and past inheritance rises to the level of reflective morality. This point continues themes broached in Tufts’ first section of Ethics, as there reflective morality is defined by the presence of principle-based activity – as Ambedkar highlights, reflective morality “involves power to see why certain habits are to be followed, what makes a thing good or bad. Conscience is thus substituted for custom; principles take the place of external rules.”[41]

The second theme that Ambedkar has noted while reading Ethics concerns the role of the individual in moral progress. Whereas texts such as Democracy and Education feature individuals as the locus of a process of habit formation, the 1908 Ethics makes a point to foreground individual reflective thinking about the problematics of morality. As we saw in the previous section – and in portions of the “Annihilation of Caste” address – getting all individuals to reason and reflect on values and ends is a vital part of escaping custom-based group morality. But “reason” is no abstract capacity of the human mind; it is really shorthand for certain useful ways of thinking through concrete problems. What can be said about these more or less abstract guides to the range of specific actions? In Dewey’s portion of Ethics, we are introduced to an important distinction for Ambedkar’s pragmatism: the distinction between rules and principles. In part two, Dewey castigates set rules of past moral theories as unresponsive to the demands of the particular situations. Ambedkar highlights Dewey’s clearest statement of these two mental shortcuts to activity with a two grey marginal lines: “Rules are practical; they are habitual ways of doing things. But principles are intellectual; they are useful methods of judging things.”[40] Habits and customs are problematic because they are based in the past and unresponsive to any given present situation, but how can one rectify or improve these remnants from a group’s past experience? One cannot be without any habit or custom. It is through the application of principles, or “useful methods” of judgment, that our activity and past inheritance rises to the level of reflective morality. This point continues themes broached in Tufts’ first section of Ethics, as there reflective morality is defined by the presence of principle-based activity – as Ambedkar highlights, reflective morality “involves power to see why certain habits are to be followed, what makes a thing good or bad. Conscience is thus substituted for custom; principles take the place of external rules.”[41]

Dewey and Tufts’ book makes it clear that the individual was to be the locus of such activities of principle-based judgment. It was the individual that was to reflect on and re-evaluate habits and customs bequeathed to them through the forces of group membership. All of this surely struck Ambedkar while he was reading this text, as his entire life was defined by the paralyzing strictures placed on him by the antiquated customs of caste morality. Elsewhere, he highlights a passage in Ethics that worries that connecting specific rules of conduct to religion and God deprives them of usefulness in an ever-changing world: “The moral life is finally reduced by them to an elaborate formalism and legalism.”[42] Reading through Ethics, Ambedkar most likely was driven to the thought that many of the Indian religions of his day were rule-based and formalistic in this fashion; he become convinced, following Dewey and Tufts, that principles held the key to a living, flexible religious approach to the world and action.

How does an individual use these powers of reflection to affect others? Dewey, in the initial two chapters in the final part of Ethics, ventures an answer. It is largely through altering the habits and activities of others through speech and persuasion. Ambedkar, noting this point, underlines in grey pencil Dewey’s argument that “liberty of thought and expression is the most successful device ever hit upon for reconciling tranquillity with progress, so that peace is not sacrificed to reform nor improvement to stagnant conservatism”.[43] Reformers of social groups must rely on such methods to attain two goals: to change society for the better, and to maintain the group itself without the application of violent force. Using speech to challenge the habits of individuals and customs of social groups can spur both to reflection on why they reacted in that specific way. This reflective activity, of course, is central to Dewey and Tufts’ account of moral progress in the 1908 Ethics.

When we look again at the 1936 “Annihilation of Caste” address, we see echoes of these themes focused on the efficacy of the individual reformer. It is the brave and outspoken individual, such as Ambedkar, who is to serve as the crisis-provoking impetus to get Hindus listening to his message to reflect on their pernicious age-old habits and customs. Ambedkar models the sort of questioning that will spur the change to reflective morality, but he betrays less optimism in the probability of being successful in his endeavour. “The assertion by the individual of his own opinions and beliefs, his own independence and interest as over against group standards, group authority and group interests is the beginning of all reform,” Ambedkar argues, “but whether the reform will continue depends upon what scope the group affords for such individual assertion.”[44] If the group has established habits of tolerance and free expression, then such reformers will have an easy path to creating more reflective modes of activity – in that case, “such individuals…will continue to assert and in the end succeed in converting their fellows”.[45] But “if the group is intolerant and does not bother about the means it adopts to stifle such individuals they will perish and the reform will die out”.[46] Hinduism, with its system of social boycott and excommunication, raises the costs for successful reform. Ambedkar uses the lack of established habits of free expression and critique as an explanation for why “individual Hindus have not had the courage to assert their independence by breaking the barriers of caste”.[47] They simply value being members of that social group too much to risk excommunication and social ostracism by pursuing the reform of caste beliefs. Ambedkar, being an outcaste in this system, has nothing to lose in being the oratorical spur to reflective morality among the high-caste Hindu reformers who may attend to his message in “Annihilation of Caste”. Like Dewey and Tufts in Ethics, Ambedkar integrally connects reflection and moral progress in his quest to spur reform in Hindu society – “Reason and morality are the two most powerful weapons in the armoury of a Reformer.”[48]

Perhaps the most important contribution of Dewey and Tufts’ Ethics is the intellectual distinction between “rule” and “principle”. Ambedkar was clearly influenced by this point, as evidenced by annotations in his copy of Ethics and in his later reconstruction of Buddhism as a religion of principle in The Buddha and His Dhamma. But we can find convincing evidence of this distinction’s effect on Ambedkar in his 1936 “Annihilation of Caste” address. In explaining what he means with his demolition of Hindu religion, he uses this exact distinction to carve out the conceptual space for religious belief and practice that is not harmful or oppressive. His address tells his anticipated audience of high-caste reformers, “I do not know whether you draw a distinction between principles and rules. But I do.”[49] What is this distinction? Ambedkar continues on, echoing in some spots the exact wording of Dewey and Tufts’ explication of rules and principles in Ethics: “Not only I make a distinction but I say that this distinction is real and important. Rules are practical; they are habitual ways of doing things according to prescription. But principles are intellectual; they are useful methods of judging things. Rules seek to tell an agent just what course of action to pursue. Principles do not prescribe a specific course of action.”[50] Rules are said to be “mechanical” and “like cooking recipes”, echoing Dewey’s portion of Ethics that criticizes abstract and non-adaptive ideals in moral theory. For Ambedkar, this is exactly what caste rules and regulations derived from texts such as the Manusmriti represent: “Now the Hindu Religion, as contained in the Vedas and the Smritis, is nothing but a mass of sacrificial, social, political and sanitary rules and regulations, all mixed up. What is called Religion by the Hindus is nothing but a multitude of commands and prohibitions.”[51] As Ambedkar states the harm of such a religion of rules, “the first evil of such a code of ordinances … is that it tends to deprive moral life of freedom and spontaneity and to reduce it (for the conscientious at any rate) to a more or less anxious and servile conformity to externally imposed rules.”[52] Life becomes rule-following, with no spur to reflect on the customs and habits driving such activity, or concerning the harm or social injustice it might be perpetuating. Reformers such as Ambedkar must strike a blow against a religion based purely on rules, since it stands as a barrier to moving a social group from the stage of customary morality to an individually instantiated reflective morality based on reason.

What type of religion ought an individual to adopt or advocate for a social group’s use? Ambedkar turns again to the Deweyan notion of principle in “Annihilation of Caste”, pointing out, “Religion, in the sense of spiritual principles, [is] truly universal, applicable to all races, to all countries, to all times.”[53] Echoing and slightly changing the words from Dewey’s section of Ethics, Ambedkar explains that “a principle, such as that of justice, supplies a main head by reference to which he is to consider the bearings of his desires and purposes, it guides him in his thinking by suggesting to him the important consideration which he should bear in mind”.[54] This concept from Ethics unites the social concerns of morality and the individual location of reflective thinking – principles are important because they are shared ways for individuals to think through problematic situations and customs. It is this insight, derived from Ambedkar’s appropriation of Deweyan pragmatism, that underlies recent evaluations of Ambedkarite Buddhism. For instance, when Valerian Rodrigues explores Ambedkar’s Buddhism as it is presented in The Buddha and His Dhamma as the form of a secularized and eminently rational faith that could serve as a sort of global religion for all, we can see this as emphasizing the transferability and communicability of principles across many people and situations.[55] Alternatively, when Ananya Vajpeyi emphasizes the aspects of Ambedkar’s reconstructed Buddhism as a way to transcend secular politics, we can see it as a principle-based way of escaping formalistic religions built upon outdated texts that contain only inflexible rules.[56] A reformer seeking to instil reflective morality in his group must start with their own reasoning processes; this much is evident in Ethics and in Ambedkar’s 1936 “Annihilation of Caste” address. The method or tool to instantiate such reflection is to connect one’s experiences of reasoning together with flexible principles which serve as general approaches to the specific and changing material of any given experience. This is what Buddhism would later represent to Ambedkar, and it was integrally related to what Hindu customs did not allow in the 1930s. Dewey and Tufts’ Ethics gave Ambedkar the vocabulary to explicitly highlight the way that the customary morality of Hinduism was held in place by rigid rules of behaviour and caste existence.

Moving beyond Dewey and Tufts’ Ethics

As I have hopefully argued, the pragmatism inherent in Dewey and Tufts’ Ethics of 1908 clearly influenced Ambedkar. Its unique moves concerning how to describe and criticize social formations gave a dimension to his theoretically sophisticated writings on caste reform not evident in his earlier writings. With the concepts of custom and habit connected to the group level of social experience, he now had a way to flesh out the story he appropriated from Dewey’s Democracy and Education that placed emphasis on social processes such as education as a way of transmitting and reforming society. Ethics gave Ambedkar a new pattern, one that implicated groups in using force to shape the habits in their members, thereby affecting the experience and happiness of their masses; it also provided an endpoint to moral critique in the idea of reflective morality. The emphasis in Dewey and Tufts’ Ethics on the individual as the harbinger of reflection in a society went beyond the focus of reconstruction in Democracy and Education and authorized Ambedkar’s own persuasive efforts aimed at high-caste reformers. Ethics provided the warrant for Ambedkar to do what he was attempting to do in such works as “Annihilation of Caste” – to shock individuals mired in past customs to reflect on what they are doing, valuing, and who they are harming with their everyday habits. This is clearly connected to the Deweyan idea of reconstruction, but it has an individualistic edge that is unique to the exposition Ambedkar read in the 1908 Ethics. Principles, for instance, became one way that an individual can affect their own experience and the experience of others for the better. If one lived according to workable principles, ones that allowed adaptation to a range of situations, then one would likely live a more happy and meaningful life. Religions of principle simply offer more of these reflective guides to more individuals across a social group.

As I have hopefully argued, the pragmatism inherent in Dewey and Tufts’ Ethics of 1908 clearly influenced Ambedkar. Its unique moves concerning how to describe and criticize social formations gave a dimension to his theoretically sophisticated writings on caste reform not evident in his earlier writings. With the concepts of custom and habit connected to the group level of social experience, he now had a way to flesh out the story he appropriated from Dewey’s Democracy and Education that placed emphasis on social processes such as education as a way of transmitting and reforming society. Ethics gave Ambedkar a new pattern, one that implicated groups in using force to shape the habits in their members, thereby affecting the experience and happiness of their masses; it also provided an endpoint to moral critique in the idea of reflective morality. The emphasis in Dewey and Tufts’ Ethics on the individual as the harbinger of reflection in a society went beyond the focus of reconstruction in Democracy and Education and authorized Ambedkar’s own persuasive efforts aimed at high-caste reformers. Ethics provided the warrant for Ambedkar to do what he was attempting to do in such works as “Annihilation of Caste” – to shock individuals mired in past customs to reflect on what they are doing, valuing, and who they are harming with their everyday habits. This is clearly connected to the Deweyan idea of reconstruction, but it has an individualistic edge that is unique to the exposition Ambedkar read in the 1908 Ethics. Principles, for instance, became one way that an individual can affect their own experience and the experience of others for the better. If one lived according to workable principles, ones that allowed adaptation to a range of situations, then one would likely live a more happy and meaningful life. Religions of principle simply offer more of these reflective guides to more individuals across a social group.

It is interesting to speculate how Ambedkar’s philosophy of emancipation might have been different had he not been exposed to the 1908 Ethics. Might he have emphasized self-respect less later in his career if he was not convinced that individual reformers, using intellectual tools such as principles, had a vital role to play in social reconstruction? Might he have emphasized the procurement of legal rights more than a religiously driven project of social reform, one that culminated in his reconstruction of Buddhism as a religion of science, reason, and democracy? Turning to Ambedkar’s November 1932 letter to V.K. Thakkar, we see an intriguing hypothetical possibility emerge as a contrast to the fully informed views of 1936 that built upon the themes of Ethics. Talking to Thakkar about the virtues of the Anti-Untouchability League, Ambedkar begins his letter by opining about “two distinct methods of approaching the task of uplifting the Depressed Classes”.[57] One approach, Ambedkar says, looks to the conduct of the individual depressed-class person as an explanation of their state: “If he is suffering from want and misery, it is because he must be vicious and sinful.” Reformers following this approach, Ambedkar says, focus their efforts on “fostering personal virtue” through building schools and libraries, encouraging temperance, and so forth.[58] Ambedkar suggests that there is another approach to solving such problems, one that starts with the assumption that “the fate of the individual is governed by his environment and the circumstances he is obliged to live under and if an individual is suffering from want and misery it is because his environment is not propitious”.[59] He tells Thakkar that this is the more correct view, and that the Anti-Untouchability League should not focus on matters of individual uplift but instead “concentrate all of its energies on a programme that will effect a change in the social environment of the Depressed Classes”.[60]

This suggestion – and apparent de-emphasizing of individual effort and focus – in his 1932 letter is as intriguing as it is indeterminate. Surely, by social environment he could be drawing upon the idea in Democracy and Education that one always educates indirectly by means of an environment. He could also be tailoring his message for the persuasive needs entailed by addressing Thakkar in this way about this social project. Ambedkar could also be imperfectly echoing Dewey’s 1922 Human Nature and Conduct gloss of the standard two (non-pragmatic) approaches to moral improvement.[61] But it is helpful to use what we know for sure of his engagement with Dewey and Tufts’ 1908 Ethics in our speculations concerning this point. Clearly, fully internalizing the lessons of Ethics would mean that the individual would play an important role in employing the means needed to achieve moral progress, as well as function as an integral part of the end itself. What Dewey and Tufts envisioned was a society created by and out of individuals practising the moral ideal of reason-based reflection on past habits in light of contemporary problems. Reflective morality was much more individualized than group-based customary morality that quashed dissent and creative inquiry from differing individuals. Principles were characteristic tools of individuals, and not specifically of material contexts or environment. It is hard to envision Ambedkar pursuing the path emphasizing material reform of social environments and still emphasizing principles in personal religious practice. Religions of principle, like his reconstructed Buddhism, were powerful precisely because they gave masses of individuals a goad and a tool for reflection on and meaning-making in their everyday experiences. Such meaning for Ambedkar encompassed personal happiness, as well as social aggregates of meaningful inclusion denoted by the western ideal of justice. Without the 1908 Ethics in his intellectual repertoire, it is tempting to speculate that Ambedkar might emphasize materialist and environmentally focused methods of social reconstruction at the cost of the religious message of self-improvement through conversion to a principle-based religion. Much more can and should be said on the contours of Ambedkar’s pragmatism, but for now it is enough to conclude that Dewey and Tufts’ 1908 Ethics deserves more than a mere mention in our stories of Ambedkar’s intellectual development. Instead, this text must be taken seriously as a deep influence on his quest to achieve social justice for his fellow Untouchables in India.

This selection is adapted and republished with permission from Scott R. Stroud, ‘The Influence of John Dewey and James Tufts’ Ethics on Ambedkar’s Quest for Social Justice,’ The Relevance of Dr. Ambedkar: Today and Tomorrow, Pradeep Aglave (ed), Nagpur, 2017.

[1] Bhimrao R. Ambedkar, “The Buddha and his Dhamma”, Writings and Speeches, vol. 11 (Bombay: Government of Maharashtra, 1992).

[2] Valerian Rodrigues, “Making a Tradition Critical: Ambedkar’s Reading of Buddhism”, in Peter Robb (ed), Dalit Movements and the Meanings of Labour in India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1993), 306; Scott R. Stroud, “Pragmatism, Persuasion, and Force in Bhimrao Ambedkar’s Reconstruction of Buddhism”, Journal of Religion 97(2), 214-243.

[3] Bhimrao R. Ambedkar, “The Buddha and his Dhamma”, 345.

[4] Ibid, 346.

[5] Eleanor Zelliot, Ambedkar’s World, 69.

[6] Arun P. Mukherjee, “B.R. Ambedkar, John Dewey, and the Meaning of Democracy”, New Literary History 40 (2009): 368.

[7] K.N. Kadam, The Meaning of the Ambedkarite Conversion to Buddhism and Other Essays (New Delhi: Popular Prakashan, 1997), 1.

[8] See Arun P. Mukherjee, “B.R. Ambedkar, John Dewey, and the Meaning of Democracy”; Scott R. Stroud, “Pragmatism and the Pursuit of Social Justice in India: Bhimrao Ambedkar and the Rhetoric of Religious Reorientation”, Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 46 (2016): 5-27; Keya Maitra, “Ambedkar and the Constitution of India: A Deweyan Experiment”, Contemporary Pragmatism, 9 (2012); Scott R. Stroud, “The Rhetoric of Conversion as Emancipatory Strategy in India: Bhimrao Ambedkar, Pragmatism, and the Turn to Buddhism”, Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric, 35 (3), 314-345.

[9] Scott R. Stroud, “Pragmatism, Persuasion, and Force in Bhimrao Ambedkar’s Reconstruction of Buddhism”.

[10] Christopher S. Queen, “A Pedagogy of the Dhamma: B. R. Ambedkar and John Dewey on Education”. International Journal of Buddhist Thought and Culture, 24 (2015); also see Christopher S. Queen, “Ambedkar’s Dhamma: Source and Method in the Construction of Engaged Buddhism”, in Surendra Jondhale and Johannes Beltz (eds), Reconstructing the World: B.R. Ambedkar and Buddhism in India (New Delhi: Oxford, 2004).

[11] Srikanth Talwatkar and the librarians at Siddhartha College must be thanked for access to Ambedkar’s personal books. Based upon his own notations, Ambedkar acquired his copy of Dewey’s Democracy and Education in London in January 1917. For my discussion of this text, see Scott R. Stroud, “What Did Bhimrao Ambedkar Learn from John Dewey’s Democracy and Education?” The Pluralist, 12 (2), 2017.

[12] John Dewey knew James Tufts from his early days as a professor at the University of Michigan. They published Ethics in 1908 while Tufts was at the University of Chicago and Dewey was at Columbia University. The book was later extensively re-written and re-published in 1932 with more focus on the social and cultural construction of individuality. The 1908 edition is characterized by an optimistic response to problems of growing industrial societies and an individualistic focus on the self as the site of realization of moral ideals. For more on the history of this text and the revised version of 1932, see Robert B. Westbrook, John Dewey and American Democracy (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991).

[13] While doing research at Siddarth College, I was able to identify and verify the following books related to pragmatism among Ambedkar’s library: John Dewey & James H. Tufts, Ethics (London: Bell and Sons, 1908); John Dewey, The Influence of Darwin on Philosophy (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1910); German Philosophy and Politics (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1915), Democracy and Education (New York: Macmillan Company, 1916), Experience and Nature (London, George Allen & Unwin, 1929), The Quest for Certainty (London, George Allen & Unwin, 1930), Freedom and Culture (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1939), and Problems of Men (New York: Philosophical Library, 1946). Some works, such as The Influence of Darwin on Philosophy, are annotated with “Columbia University” and a date that falls within the range of his stay at Columbia. His copy of Democracy and Education is noted as acquired in London in January 1917.

[14] This inference comes from the textual apparatus to the critical edition of the Ethics, which indicates that “George Bell and Sons” being noted above the “Henry Holt and Company” line on the title page is unique to a rare British re-issue of this American book. See John Dewey, “Ethics”, in Jo Ann Boydston (ed), The Middle Works of John Dewey, Vol 5 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press), 554.

[15] Christopher S. Queen, “A Pedagogy of the Dhamma: B. R. Ambedkar and John Dewey on Education”. International Journal of Buddhist Thought and Culture, 24 (2015): 8.

[16] Gail Omvedt, Ambedkar: Towards an Enlightened India (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) 5-6.

[17] Dhananjay Keer, Dr Ambedkar: Life and Mission (Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1990), 19-20.

[18] Ibid, 21.

[19] There is also evidence that Keluskar continued to help Ambedkar in his struggles as a fledgling professor upon his return to India in 1917. See Keer, Dr Ambedkar: Life and Mission, 35.

[20] Bhimrao R. Ambedkar, “Castes in India”, Writings and Speeches, Vol 1 (Bombay: Government of Maharashtra, 1989); Bhimrao R. Ambedkar, “Evidence before the Southborough Committee”, Writings and Speeches, Vol 1 (Bombay: Government of Maharashtra, 2014).

[21] Bhimrao R. Ambedkar, “Annihilation of Caste”, Writings and Speeches, Vol 1 (Bombay: Government of Maharashtra, 1989).

[22] Bhimrao Ambedkar, “Letter 72”, Letters of Ambedkar, Surendra Ajnat (ed) (Jalandhar: Bheem Patrika Publications, 1993), 79-80.

[23] Ibid, 81. For more on the dating of his copy of Democracy and Education, and the themes it presents, see Scott R. Stroud, “What Did Bhimrao Ambedkar Learn from John Dewey’s Democracy and Education?”

[24] John Dewey and James H. Tufts, “Ethics”, in Jo Ann Boydston (ed), The Middle Works of John Dewey, Vol 5 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1908/1985),

[25] This is a rather curious fact. One could speculate that this is a clue that it was used as a textbook in one of Dewey’s classes that Ambedkar took, but I have found no evidence that it was assigned or systematically engaged during any of the three semesters Ambedkar was exposed to Dewey’s lecturing.

[26] John Dewey and James H. Tufts, “Ethics”, 7. I will refer to the pagination given in the critical edition of Dewey’s works.

[27] Ibid, 13.

[28] Ibid, 42.

[29] Ibid, 54.

[30] Ibid, 74

[31] Ibid, 194.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Bhimrao R. Ambedkar, “Annihilation of Caste”.

[34] Ibid, 50-51;

[35] Ibid, 73.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Scott R. Stroud, “What Did Bhimrao Ambedkar Learn from John Dewey’s Democracy and Education?”

[39] Bhimrao R. Ambedkar, “Annihilation of Caste”, Writings and Speeches, Vol 1 (Bombay: Government of Maharashtra, 1989), 78.

[40] John Dewey, “Ethics”, 301.

[41] Ibid, 167.

[42] Ibid, 295.

[43] Ibid, 399.

[44] Bhimrao R. Ambedkar, “Annihilation of Caste”, 56.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid, 74.

[49] Ibid, 75.

[50] Ibid. For more on this technique of “echoing” in Ambedkar, see Scott R. Stroud, “Pragmatism and the Pursuit of Social Justice in India: Bhimrao Ambedkar and the Rhetoric of Religious Reorientation”; Arun P. Mukherjee, “B.R. Ambedkar, John Dewey, and the Meaning of Democracy”.

[51] Bhimrao R. Ambedkar, “Annihilation of Caste”, 75.

[52] Ibid, 75-76.

[53] Ibid, 75.

[54] Ibid, 75.

[55] Valerian Rodrigues, “Making a Tradition Critical: Ambedkar’s Reading of Buddhism”, 306.

[56] Ananya Vajpeyi, Righteous Republic: The Political Foundations of Modern India (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012), 224.

[57] Bhimrao Ambedkar, “Letter 72”, Letters of Ambedkar, Surendra Ajnat (ed) (Jalandhar: Bheem Patrika Publications, 1993), 77.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Ibid, 78.

[61] John Dewey, “Human Nature and Conduct”, in Jo Ann Boydston (ed), The Middle Works of John Dewey, Vol 5 (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press), 9. In my research at Siddharth College and elsewhere, I have not found any evidence that Ambedkar owned this book.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +919968527911, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy: