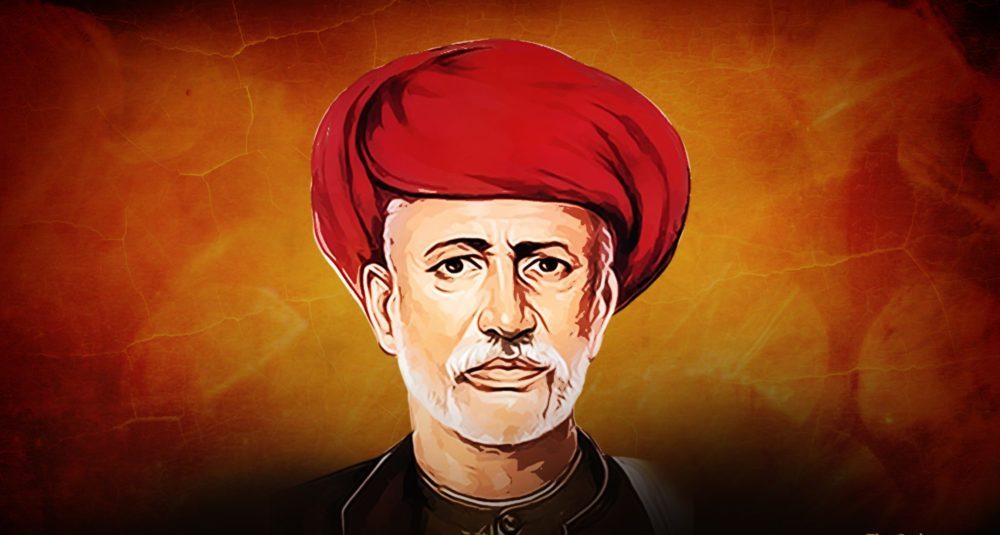

Gulamgiri: Jotirao Phule’s re-rendition of Hindu mythology

Jotirao Phule, respectfully addressed as Mahatma Phule, is considered one of the intellectual giants of the 19th century. Among the thinkers who laid the foundations of the Indian renaissance of the 19th century, Jotirao Phule was endowed with extraordinary scientific temper. His Satyasodhak Samaj, a social-reform organization, was wedded to the mission of distilling out the truth. He wrote prolifically from 1855 till his death. One of his important works is his book Gulamgiri (1873), which he dedicated to the Americans who fought to free the Blacks from slavery. Jotirao Phule compared India’s Shudras and Ati-Shudras to the black slaves of America and expressed solidarity with the Americans who rose against the system of slavery.

One of Jotirao Phule’s outstanding qualities was that he wrote for the people and in their language. Though most of his writings are in Marathi, he would switch to English when he wanted to reach out to the British rulers. Besides essays, letters and ideological treatises, he also penned poetry to voice his disdain of evil religious practices and blind faith prevalent in society. Jotirao categorically said, “Those who praise the Vedas should be sent to live among the brainless animals[1].”

Gulamgiri, which is written in the form of a dialogue, constitutes two characters – Phule himself and Ghondirao. Their conversations expose the truth behind the Hindu mythology, their deities and culture, and show how the Aryan-Brahmanical forces divided the majority Bahujans and subjugated them.

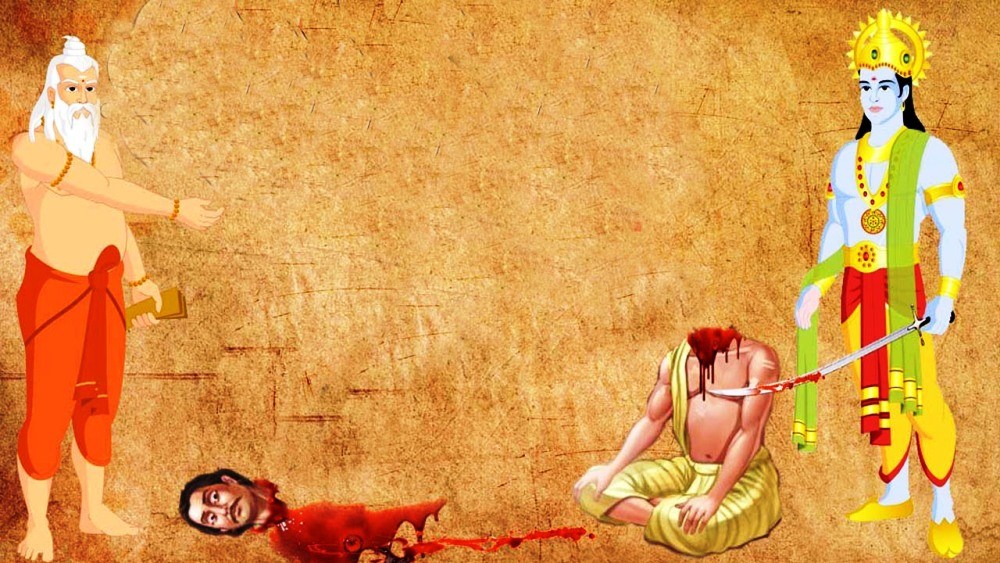

In the introduction to Gulamgiri, he lambasts the Hindu mythological character Parshuram. Jotirao writes about the cruel behaviour of Parshuram, the head of the Brahmin class, towards the original Kshatriya inhabitants of the country.[2] After detailing the severe exploitation, oppression and inhuman treatment of the Shudras and Ati-Shudras by the Brahmins, he explains how the Brahmins enslaved them despite their population being ten times that of the Brahmins. He points out that as the numbers of the Shudras and Ati-Shudras began to rise, the Brahmins started feeling threatened and drew up a plan to sow seeds of mutual hatred among them.

Also read: Phule’s tribute to those who opened his ‘third eye’

To ensure that their strategy succeeded and that their ideology was accepted, the Brahmins created impregnable and poisonous “walls” separating one caste from the other, and then produced a litany of scriptures to serve their caste interests. For the ignorant, these scriptures became gospel truth. Those who doggedly took on the Brahmins were segregated, thrown out of society and declared “Untouchables”. The Brahmins and the priests injected the poison of “touchable-untouchable” binary into the hearts and the minds of the people. The system of untouchability led to the social exclusion of a class of people, who were pushed into starvation and misery. That is why they had to eat the meat of dead animals[3].

Mahatma Phule thus explains how the Brahmins punished those who dared to revolt against them by declaring them “untouchable” and segregated the other indigenous inhabitants into different castes according to the services they provided – such as gardeners, vegetable growers, goldsmiths, ironsmiths, carpenters, telis (people who make cooking oil) and kurmis (agriculturists). And among these “touchable” others, some were accorded a higher status than the others. These divisions gave immense advantage to the Brahmins. The indigenous inhabitants started quarreling among themselves, in the name of caste superiority while the priestly class started living off their labour.

Given this plight of the Shudras and Ati-Shudras, Mahatma Phule considered the arrival of the British in India a welcome development for them. He wrote, “The British Government has brought a new light into the lives of the Shudras and Ati-Shudras of this country. We have no hesitation in saying that [because of the British government] they have been freed from the slavery of the Brahmins. But we are sorry to say that because of the government’s irresponsible attitude towards educating the Shudras and Ati-Shudras, they have remained illiterate. Others, despite getting an education, continue to blindly believe in the fake-hypocritical [religious] scriptures of the Brahmins and thus continue to be slaves mentally.”[4]

Almost every chapter of Gulamgiri refers to one or the other mythological story. For instance, the first chapter of the book has a reasoned analysis of the tales and characters of the Puranas with regard to the origin of Brahma and Saraswati, and the Iranian or Aryan people.

“The kind-hearted British, French and other governments in Europe collectively abolished slavery (in their empires) and thus transgressed the fiats of Brahmhadev (Virat Purush). For it is said in the Manusmriti that Brahmadev created the Brahmin from his mouth and the Shudras from his feet and ordained them to serve the Brahmins eternally,”[5] says Ghondirao.

Phule asks, “Many races like the English live on this earth. From which parts of Brahmadev’s body were these races created, according to the Manusmriti?” Ghondirao responds, “There is no reference to the English and other people (races) in the Manusmriti, as they are an abusive and vicious people,” The dialogue between Jotirao and Ghondirao continues and ultimately Ghondirao concedes that the theory of origin of Varnas, which Manu has propounded in his laws, is baseless and devoid of truth because it cannot and does not apply to the entire human race.

In the course of the conversation, Ghondirao tells Jotirao, “You have declared openly in public meetings that the original ancestors of the Brahmins, the venerable Rishis, were in the habit of killing cows and enjoying beef delicacies on death anniversaries.”

Jotirao lays bare the unscientific approach of Manu’s laws and the conspiracies of the Brahmins. He also analyzes the mythical character of Saraswati.

At the end of the first chapter, Jotirao says that the Aryans had come to India from Iran, hence Brahmins were initially called Iranians. Only later were they referred to as Aryans. Hordes of these Aryans launched a brutal attack on India’s indigenous peoples and terrorized them. He argues that Brahma must have been the head of the Aryans, who vanquished and enslaved our ancestors. Later, to perpetuate the difference between his people and the slaves, he laid down a web of rules and norms. After Brahma’s death, the Aryans came to be known as “Brahmins”.

Leaders like Manu, who succeeded Brahma, made up stories about Brahmins, investing them with divine will and grace. This was done to leave the conquered people convinced that slavery was divine will. Manu invented not only his laws but also other mythological tales.

In the second chapter, Jotirao analyzes the mythical tales about Matsya and Shankasur to prove that the Aryans had travelled by sea to reach western India from Iran. That is why their chieftain was called Matsya (fish). Matsya killed Shankasur, the chieftain of the place where the Aryans disembarked and which Matsya usurped first. After Matsya died, the local people launched an attack on his successor, and he was forced to hide in the forests. Just then, another Aryan horde arrived. The boats they came in were of the shape of a tortoise, hence, the locals nick-named the captain “Kacchha”.

The third chapter analyzes the prevalent mythological tales revolving around Kacchha, Bhudev, Bhupati, Kshatriya and the Kashyap kings. It says that Kacchha freed the people of the Matsya clan, drove out the indigenous inhabitants and became the Bhudev or Bhupati (ruler of the land). Kashyap was another indigenous ruler and his territory lay on the other side of the mountain near the port. He tried his level best to recapture the mountain from Kacchha and Matsya hordes, but did not succeed.

The fourth chapter contains a dialogue on Varaha and Hiranyagarbha. Jotirao believes that after the death of Kacchha, Varaha became the leader of the Aryans. Varaha was reprehensible in terms of his nature, his conduct and and the way he lived, and wherever he went, he had a boorish way of achieving his objective. Hence, two valiant Kshatriyas – called Hiranyagarbha and Hiranyakashyapu – named him “varaha” or wild boar. This incensed Varaha so much that he launched repeated attacks on their kingdoms and ultimately, in one battle, Varaha killed Hiranyagrabha. After some time, Varaha also died.

In the fifth chapter, Jotirao has analyzed the prevalent mythological tales about Narsimha, Hiranyakashyapu, Prahlad, Vipra, Virochan and others. He believes that Narsimha succeeded Varaha as the chieftain of the Dwijs. Jotirao describes Narsimha as greedy, treacherous, cunning, dangerous, cruel and corrupt.[6] But Jotirao also says he was strongly built. Narsimha looked to usurp the kingdom of Hiranyakashyapu, a Kshatriya king. In order to get what he desired, he tried to influence the impressionable prince, Prahlad. This he did by means of a Brahmin tutor, who inducted young Prahlad into the basic tenets of the Brahmin religion and provoked him to kill his father. When the young prince could not gather the courage to do so, Narsimha, with Prahlad’s help, entered the palace of Hiranyakashyapu and hid behind a column in Hiranyakashyapu’s bedroom. To hide his identity, he dressed up as a lion. Exhausted by the day’s work, as Hiranyakashyapu went to bed, Narsimha emerged from behind the column and murdered him using his claws.

As he feared that the murder might lead to attacks on his Dwij followers, he fled the kingdom of Hiranyakashyapu along with his subjects. When the Kshatriyas came to know of this inhuman act, they stopped addressing the Aryans as Dwijs and started calling Narsimha “Vipriya”. It is possible that the word “Vipra” used to address Brahmins emerged from the word “Vipriya”. To cover up the treachery of Narsimha, the Brahmins deliberately mythologized the incident and presented it as divine will. Hiranyakashyapu’s murder was an eye-opener for Prahlad, who became distrustful of the Vipras. Prahlad’s son was Virochan and Bali was Virochan’s son. Bali, a great warrior, expanded his kingdom and Vamana, the chief of the Vipras, could not digest the expansion of Bali’s kingdom. He put together a huge army and approached Bali’s kingdom with the intent of conquering it.

(To be continued)

Translated by Amrish Herdenia

[1] Jotiba Phule Rachnavali Volume 1, ed L.G. Meshram, Vimal Kirti, Introduction

[2] Gulamgiri, ibid, p 141

[3] Gulamgiri, ibid, p 146

[4] Gulamgiri, ibid, p 147

[5] Gulamgiri, ibid, p 149

[6] Gulamgiri, ibid, p 161

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +919968527911, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History