In the brahmanical tradition, “Ramrajya” is the ideal kingdom and Ram is the greatest ruler ever born. But subjects of the Ramrajya had to follow the varna system. In other words, the Shudras and the Ati-Shudras had to serve the dwijs, and women were had to be subservient to men. Violation of the tenets of the varna system invited death and the king, Ram, himself executed the sentence. In contrast, the Bahujan-Sraman tradition witnessed many kings who upheld justice and worked for public welfare in every sense. They devoted their lives to the arduous task of dismantling the varna and the caste system, and the elaborate structure of discrimination based on it. Shahuji Maharaj was one of them. He concretized the dreams of Jotirao and Savitribai Phule.

Shahuji was anointed the king of Kolhapur on 2 July 1894. Soon, he was loosening the stranglehold of Brahmins on the administration and society. On 26 July 1902, he took a path-breaking step – something no one had even imagined. Amid stiff opposition from the Brahmins, he implemented 50 per cent reservations for Dalits and the Backwards in educational institutions and in government jobs in his state. This was the first instance of caste-based reservation in modern India. That is why Shahuji Maharaj is often described as the father of modern-day reservations. Later, Dr Ambedkar incorporated the pioneering initiative of Shahuji Maharaj in the Indian Constitution. The Constitution mandated reservations for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, but the decision on OBC castes was kept open. The OBCs got reservations on 16 November 1992, about 45 years after Independence and 90 years after Shahuji made the provision for his subjects.

In 1894, when Shahuji took over as ruler, Chitpavan Brahmins had monopolized most of the positions in the administrative set-up of Kolhapur. Brahmins occupied 60 of the 71 senior administrations positions. There were only ten non-Brahmins among the 500 clerks. Following the implementation of Shahuji’s reservation policy, only 35 Brahmins were left among the 95 administrative officers in 1912.

Shahuji was in complete agreement with what Phule wrote in his Gulamgiri:

“Without education, wisdom was lost,

without wisdom, morals were lost,

without morals, development was lost,

without development, wealth was lost,

without wealth, the Shudras were ruined,

so much has happened through lack of education.”

Shahuji Maharaj took upon himself the task of combating ignorance and lack of education among Dalits and the backward castes. By as early as 1912, he had made primary education compulsory and by 25 July 1917, he had made it free. He was the first Indian ruler to do so. Like the Phule couple, he laid great stress on women’s education. He opened schools in all villages, each to serve a population of at least 500 and up to 1,000. In 1920, he established a free hostel named Prince Shivaji Maratha Free Boarding House.

We all know that the brahmanical Peshwa rule had led to Brahmin dominance in every field of life – religious, political, economic and social – in Maharashtra. They were in control of almost everything. With the provisions of 50 per cent reservation and free and compulsory education, Shahuji aimed at ending that dominance. He also decided to dismantle the brahmanical supremacy on religion. On 9 July 1917, he issued a declaration that the income and the assets of religious institutions in Kolhapur belonged to the government. He also ordered that Marathas (a backward caste) be appointed priests in temples. In 1920, he established a school to train priests in conducting religious rituals. We all know about Dr Ambedkar’s Hindu Code Bill, but few of us are aware that Shahuji Maharaj also passed a Hindu Code Bill on 11 November 1920, ending the stipulation that Hindu succession laws would be governed by the Mitakshara School of Law. Mitakshara is Vijnaneswara’s commentary on Yajnavalkya Smriti and broadly rules that women cannot inherit the property of their families. It imposes several conditions and restrictions. Shahuji also brought to a close the tradition of assigning villages to Brahmin priests,

Shahuji took a series of steps to ensure that the Untouchables (Dalits) were treated on a par with others and to improve their living conditions. Until 1919, no Untouchable could get treatment in a hospital. In 1919, Shahuji issued a declaration that any Untouchable could visit a hospital and get treatment. In the same year, he issued another order outlawing discrimination in primary and high schools and in colleges against students on the basis of caste. Besides ensuring that Dalits got a foothold in government service, he also issued an order that said Dalit government employees should be treated with dignity and respect, and that government offices should be free of the practice untouchability. “The officers who are unwilling to follow this order should resign within six months,” the order said.

He outlawed two obnoxious traditions, thus bringing about a sea change in the position of Dalits in society. First, in 1917, he abrogated the archaic Balutdari system, under which an Untouchable was given a small piece of land and in return, he and his family had to render all kinds of services to the entire village without any compensation. Second, in 1918, he promulgated a law putting an end to the oppressive Vatandari system and introduced land reforms to enable Mahars to become owners of land. This ended the economic slavery of Mahars to a great extent. The pro-Dalit Kolhapur ruler, with obvious pride, told a vast assemblage of Dalits in Manmad in 1920: “I believe you have got an emancipator in Dr Ambedkar. I hope that he will break your chains of slavery.” He not only showered praises on Ambedkar but also helped him complete his education abroad and make politics a weapon for the emancipation of Dalits.

Shahuji’s efforts to secure equality and justice for the Backwards, Dalits and women earned him the ire of the Chitpavan Brahmins of Maharashtra. Numerous efforts were made to humiliate and run him down.

Ordinary Brahmins hating Shahuji can be understood. After all, he had ended their dominance in society. But what was painful was that people like Balgangadhar Tilak and Sripad Amrit Dange, a founding member of the Communist Party of India, also brimmed with anger and hatred towards him. Tilak fought a running battle with him.

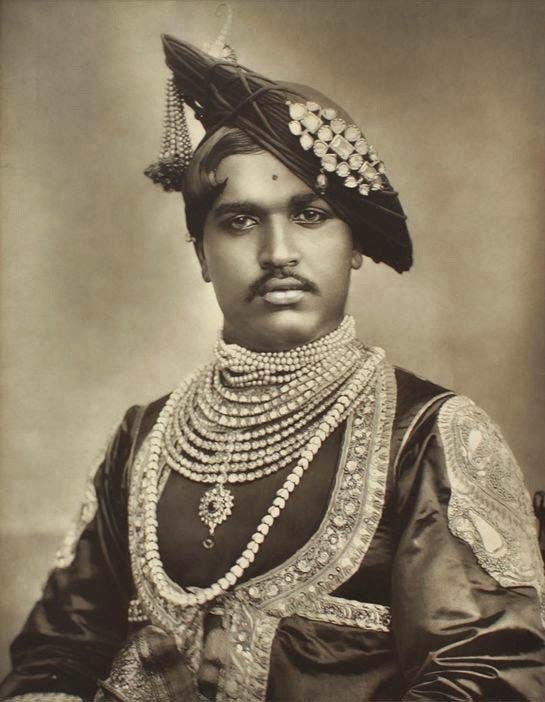

Born into a Kunbi (Kurmi in North India) family on 26 June 1874, Shahuji Maharaj became the ruler of Kolhapur when he was just 20 and ruled the state for 28 years. He was the grandson of Chhatrapati Shivaji and the son of Aapasaheb Ghatge Kagalkar. Yashwant Rao – as he was called in his childhood – lost his mother when he was just three years of age. Anandibai, the queen of Kolhapur, adopted him on 17 March 1884, and the title of Chhatrapati was conferred on him. In June 1902, the Cambridge University conferred on him an honorary doctorate of law. He was the first Indian to receive the honour. He was honoured with the title of Rajashri at the 13th national convention of the Akhil Bharatiya Kurmi Mahasabha held in Kanpur from 19-21 April 1919. He was also a recipient of the titles of GCSI, GCVO and MRES.

This great emancipator of the Backwards and Dalits breathed his last on 6 May 1922, aged 48. But the lamp which he had lit, inspired by Phule, is illuminating our lives even now.

Translated by Amrish Herdenia

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +919968527911, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History