(V.S. Naipaul: 17 August 1932 – 11 August 2018)

Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul is no more. He passed away on the night of 11 August 2018. He was 85. Naipaul was a Trinidad-born British citizen of Indian origin. In the 1880s, destiny landed his forefathers in Trinidad, and they stayed put there. People who are uprooted from their soil and their country have a typical psyche, which is difficult to understand. Understanding Naipaul warrants some special tools. Russian critic Nikolay Chernyshevsky had said that to understand a writer’s works, it is necessary to understand his life.

Naipaul’s childhood must have been a hard one. In 1950, when he was 18, he moved to England after getting a scholarship to study at Oxford University. He began writing in 1954. He devoted his entire life to writing – and adopted no other profession – so, he could write a large number of books.

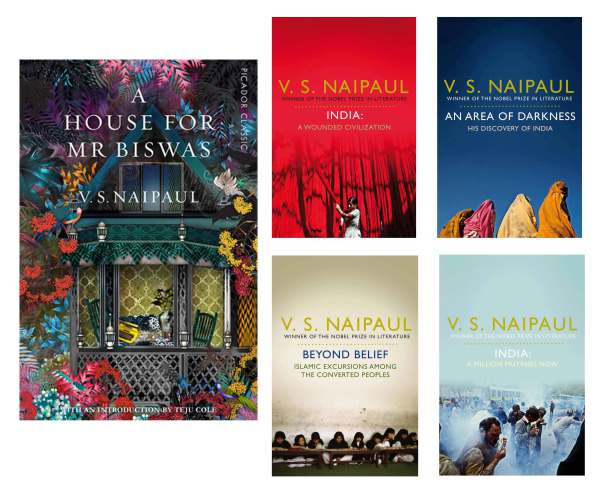

In 1971, he won the Booker Prize for his novel In a Free State and then in 2001, the Nobel for A House for Mr Biswas. Besides fiction, his travelogues and his writings on the contemporary social issues were also well received. He had his own views on different issues, which made him controversial, but also underlined his original thinking. I have not read him much, only A House for Mr Biswas, India: A Wounded Civilization and a couple of interviews and articles.

Naipaul was mired in controversies. There was an India inside him and he loved it too much. But his India was different from Tagore’s India. Even if he wanted to, he could not become a Tagore. He was an immigrant from India and he saw India from the eyes of the rest of the world. Tagore, on the other hand, saw the world from an Indian world-view. But with some differences, both had a global consciousness. They were not frogs in the well. Naipaul did not see the world as a philosopher – like Tagore did. He saw it as a journalist – an eagle-eyed journalist – and sometimes he seemed to be playing mischief deliberately.

Naipaul was often accused of being a right-winger. I cannot comment on that but I did hear BJP leader L.K. Advani telling an interviewer that he cancels all his programmes to watch Naipaul’s interview or any other programme on the writer on television. Naipaul was neither a leftist nor a secular in the Indian context. He wife was a Muslim of Pakistani origin but he was a bitter critic of Islamist consciousness. In our country, being critical of Islam is enough to brand you as a rightist. He kept on visiting India and used to freely comment on social and political developments in the country. He almost glorified the razing of the Babri Masjid in 1992 by describing it as “an act of historical balancing”. About Pakistan, he said, “The story of Pakistan is a terror story actually. It started with a poet who thought that Muslims were so highly evolved that they should have a special place in India for themselves.”

However, he condemned the ways of the Hindus and their obscurantism with equal vehemence. Some of his comments on Gandhi, Vinoba Bhave and Jayaprakash Narayan were shocking. His book India: A Wounded Civilization is in a class of its own. It talks about India of the Emergency era. You may or may not agree with him but he does force you to reflect. In the preface to the book, he writes, “India is for me a difficult country. It isn’t my home and cannot be my home; and yet I cannot reject it or be indifferent to it; I cannot travel only for the sights. I am at once too close and too far.” His forefathers migrated from the plains of Ganga about a hundred years ago and, to Naipaul, the Indian society which they built at the other end of the world – in Trinidad – was much more integrated than the Indian society that Mahatma Gandhi encountered in South Africa in 1883.

Also read: Buy Forward Press books from The comfort of your homes

The book is a factual, ruthless analysis of the sociopolitical developments, movements and some leaders in post-Independence India. Commenting on the JP (Jayaprakash Narayan) Movement, Naipaul wrote, “His revolution was an expression of rage and rejection; but it was a revolution without ideas. It was an emotional outburst, a wallow; it would not have taken India forward. At its core was a distorted form of the old Gandhian call for action, which was given the form of an absurd political programme. At its core were old tendencies of defeat, the concept of turning back, of getting immersed in the past and of re-discovering the old ways.” And, “A synthesis of Marxism and Gandhism, which, according to JP’s followers, he had done, was a sort of unrestrained delirium.”

In this piece, I have just attempted to bring to the fore some instances of his candour. This is not the time for a detailed discourse on him. That, we will leave for some other day.

Naipaul is no more. This is my tribute to him.

Translation: Amrish Herdenia

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History