Politician-turned-litterateur, Bahujan thinker and theoretician Shri Motiram Shastri published a booklet of verses comprising 13 chapters – Ravan Lanka – in the 1980s. From the point of view of ideas the poem seeks to communicate, it is amazing poetry. He wrote in chapter “Tathagat” (a name for Buddha):

“Ravan ka putla mat foonko, ye Ravan nahi tathagat hain.

Das paarmita das baldhari, hain yehi ateet annagat hain.

Pragya data hain prabha punj, kotik jan man nayak hain.

Manavta ke aviral prateek, pooja archan ke layak hain.

Tap, Yagya, Bramha hare jis se, vishayi hai bhu pati nyare hain.

Hai yahi katha yedi Ravan ki, to bolo kisne mare hain?

Chalne par dhara hili kiski, tha traahi-traahi ghanghor kahan?

Kitna atpata mukadamma hai, jab mal nahi to chor kehan?

[Don’t burn Ravan’s effigy for he is true to himself. He possesses 10 virtues and his strength equals 10 men. He is the past and the future as well. He is the giver of wisdom. He is adored by the multitudes. He is eternal symbol of humanity, fit to be worshipped. Even Brahmans’ penance, Yagya and Brahma’s intervention, couldn’t destroy him. He is a scholar and the darling of his domain. If this is the true story of Ravan, then who killed Ravan? His forceful suppression of wrongdoers created terror among them. How strange is this justice that an innocent man is branded guilty! (translation in prose)]

In the chapter, the lines “Das paarmita das baldhaari”, “Tap, yagya, Brahma haare jis se” and “Chalne par dhara hili kiski, tha traahi-traahi ghanghor kahaan?” carry special meaning. Motiram Shastri says Ravan is a symbolic representation of the historic Buddha. Ten “paarmitaayen” denote ten heads, which are installed on Ravan’s effigy. Because of his powerful physique, Ravan is also called Das Kandhar (ten shoulders), which is akin to Das Skandha in Buddhist literature. Ravan fought Ram and Buddha waged war on evil (Mar). Reading Mar backwards we get Ram, not Mara. Buddha had a cousin brother (brother’s son) Devdatt who held a grudge against him. Similarly, Ravan too had a brother, Vibhishan, who held a grudge against him. That brother was responsible for his death. Ravan’s life lay in his naval, which was struck by arrow, thus killing him.

The naval is the midpoint of the human body, which is akin to Buddha’s Middle Path. To vanquish Buddhism, Brahmins attacked the Middle Path. It is clear that brahmanical “penance, yagya and Brahma” lost the battle to none other than Buddha. Who put an end to the violent yagyas? Ravan or Buddha?

The answer: Buddha in reality and Ravan in myth. Buddha had become an object of hatred following his stand against violent yagyas. That is why it was necessary to erase his legacy. According to history, this was done by Pushyamitra Shung, who was the Brahmin general of Buddhist emperor Brihadutta. He established the Shung dynasty by assassinating the emperor, and using state force he carried out genocide of Buddhist monks, and destroyed viharas, sangharams, mathas and stupas.

It is worth mentioning that Ramayan was created during this period and Manusmriti was produced as a law to strengthen the ruling dynasty. This is why both the Ramayan and the Manusmriti are replete with hatred towards Buddha. According to the Ramayan, formidable Asurs killed hundreds of Brahmins each day. This explains clearly the line, “Chalne par dhara hili kiski, tha traahi-traahi ghanghor kehan?” (His forceful suppression of wrongdoers created terror among them).

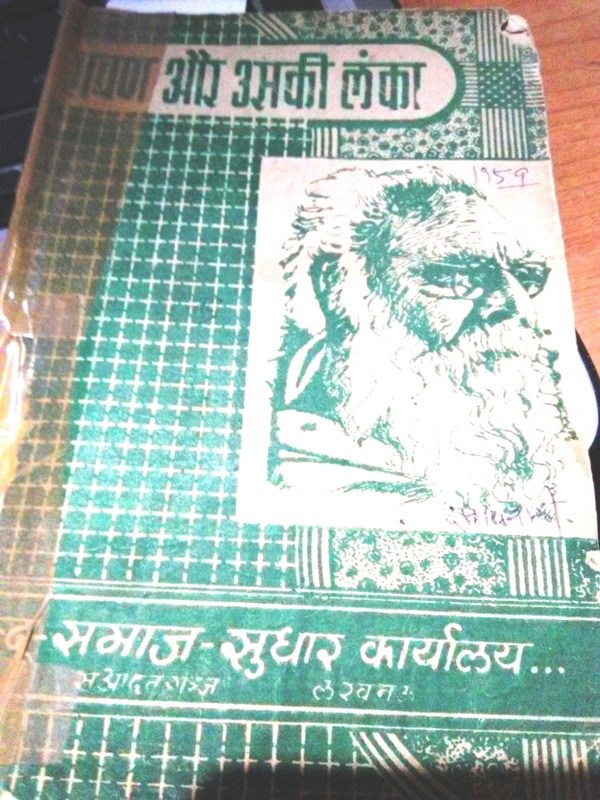

Ravan and his Lanka

Chandrika Prasad Jigyasu was perhaps the first Bahujan litterateur to work on Ravan in Hindi. His book Ravan aur uski Lanka was first published in 1959. This was his most talked-about book. He states in the early part of his book, “According to the Hindu calendar, Ravan was killed towards the end of the Treta Yug. Since then 86.4 million years of Dwapar Yug and 5,000 years of Kaliyug have passed, but each year the death anniversary is celebrated by burning the effigy of Ravan.”

Jigyasu elaborates:

“Through Ramleela, it is impressed on the audience that Ravan is an evil incarnation; that he had rejected the Vedic religion and persecuted the Brahmins and the Devtas; that he had banned yagyas, japas, homas, recital of kathaas-puranas; and that he had banned Brahmabhoja, Shraddhbhoja and so on. Therefore, Brahmans and Devtaas requested benevolent god Vishnu and he, in the incarnation of Ram, annihilated Ravan and his dynasty. What this means is when the Ramleela celebration as a religious event becomes a success, the Brahmins consider it their religious victory because it is generally the Brahmins who are the inspiration, motivators, leaders, managers, volunteers, guides and actors.”

Jigyasu rightly considers Ramleela of the Brahmins as a religious triumph. Through these Ramleelas, the Brahmins aim at the perpetuation of Brahmanism, Thakurs establish their dominance and the Baniyas’ business flourishes. The ignorant Bahujan community makes up the audience, and when Ravan’s effigy is ignited, they rejoice the most. This joy prolongs the life of Brahmanism.

In Chapter 3 of this book, Jigyasu writes: “Valmiki’s Ramayan doesn’t support the view that Ravan had 10 heads, 20 eyes, 20 hands and the topmost head was a donkey’s. Or that his kindred had long teeth like those of predators and horns like those of bulls. Or that they were cannibals who killed humans and ate their raw flesh like tigers. Or that they would loaf around in drunken stupor all the time. We learn from Valmiki that Ravan was a first-rate statesman and intellectual, a cultured and refined man, and that his Lankapuri was a civilized city. Valmiki thus described what Hanuman saw in Lanka while searching for Sita:

“In the evening when the bachelor Hanuman entered the resplendent city of Lankapuri divided by wide roads he saw that roads were lined with huge mansions, which had golden pillars. These mansions had large golden windows. Lanka appeared to be a grand city of Gandharvas (lower class of Hindu gods). Hanuman saw that several houses were diamond-shaped or round or hook-shaped … and some were shaped like swastika, which by their beauty dazzled Lankapuri.”

Thereafter, Valmiki has described Ravan in these words, “When in search of Sita Hanuman reached the bedroom of Ravan, he saw Ravan sleeping. The king of Rakshas was sleeping with his arms stretched wide and they looked like the flag of the Indra. Both arms bore wounds of elephant attack. He arms were muscular. He wore a white dhoti and a fine yellow dupatta.”

Based on the eye-witness account of Hanuman, Jigyasu concludes, “The sickening, loathsome, disgusting and malicious image of Ravan – that he had 10 heads with a donkey head at the centre – vanishes into thin air as if it never existed.”

Was Ravan a Brahmin?

In The Hindus: An Alternative History, Wendy Doniger writes that Ravan was a Brahmin and a devotee of Shiva. It is understandable that Ravan was Shiva’s devotee because non-Aryans worshipped Shiva, who was later assimilated with the Vedic god Rudra and presented in distorted form as a junkie and debauched. Had he been a Brahman he wouldn’t have been given titles like Rakshasraj and Rakshaseshwar, meaning king of Rakshases.

Had he been a Brahmin, according to brahmanical religion, he couldn’t have been assassinated. This custom remained unaltered under the Mughal rule, and it continued under the English too until 1817, when Brahmins’ immunity from capital punishment was revoked. Even if a Brahmin committed the most heinous kind of crime, under Manu’s law, he couldn’t be awarded death punishment; he could only be exiled. Then how could Ravan be murdered? Why did the Brahmin violate his own law? Year after year, Brahmins murder him and set him on fire. Why is Ravan subjected to so much humiliation? It is obvious that Ravan was not a Brahmin. The war between Ram and Ravan was not a war of Aryan versus Aryan, which was not possible. Ravan was non-Aryan and he was the custodian of Rakshash culture of Rakshsh tribe. Rakshash, Danav, Daitya, Asur, Vaanar were names of different communities. Therefore, the Ram-Ravan war was a war for cultural imperialism. It was a war to wipe out non-Aryan culture and to establish the dominance of Aryan culture in the land, just as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) are creating their dominance in the tribal regions today.

Ravan’s character

Here, it would be interesting to recall an extract of Harimohan Jha’s book Khattar Kaka:

‘Me: So you are sure that that there isn’t a single character in Ramayan who can be regarded as ideal?

Khattar: Of course not, there is one.

Me: Who is he?

Khattar: (smiling) Ravan.

Me: But he had kidnapped Sita.

Khattar: That was so because the maryadapurushottam (Ram) had to be taught a lesson that nobody has a right to cut off anyone’s nose and ears. When living in alien land one should not go around making enemies. One should not be chasing mirages. Women should not be dishonured. Note that Ravan did not dishonour Sita even after confining her in Lanka. He did not force her to live among his queens but housed her separately in Ashok Vatika. Many regard him Rakshash but few can match his conduct as a cultured man.

Was Ravan a foreigner?

Arya Samaji scholar Raghunandan Sharma has stated in his work Vedic Sampatti – which is literature of the Satyarth Prakash type and is taught in gurukuls – that a group of foreigners came from Australia to India via Sri Lanka and settled in the Madras region. He goes on: The leader of this group was Ravan, who, besides being a scholar and warrior, was also debauched; but after the defeat of Ravan the remaining non-Aryans became Hindus and some even established lineage with the Ravan family to become Brahman.

This school of thought considers Ravan as a foreigner and non-Aryan Dravidian. If Ravan was a foreigner, then he had to be Aryan. If he was a foreigner, and had settled in Madras, then where was his Lanka, whose king he was? Raghunandan Sharma has not been able to explain this. The author of Vedic Sampatti goes to the extent of stating that “Dravidians glorified their ancestor Ravan to the point of including his name in the mantras. A healing mantra named Chakradutt pays obeisance to Ravan: “Om namo Ravanai amukasya vyadhi han-han munch-munch hvi fatswaha.”

Chandrika Prasad Jigyasu has rejected the opinion that Ravan was a foreigner. “The basis of this view is Shri Malladi Venkata Ratnam’s book Rama: The Greatest Pharaoh of Egypt, which says that the entire story of Ram and Ravan is the story of Ramesses II of Egypt and that Dashrath, Kaushalya, Ram, Lakshman, Sita, Vashishth didn’t exist in India at all. By accepting this opinion or by being insolent and audacious enough in treating Asurs as Assyrians, the entire Ramayan will become an alien mythology and confusion will be compounded.”

A Dravidian leader’s view

Periyar Ramasamy Naicker, the leader of the Dravidian movement, writes in his much-discussed book The Ramayana: A True Reading that Ravan loathed Vedic gods and rishis because in the name of yagyas they would offer to the sacred fire life of voiceless and hapless animals. Referring to Valmiki’s Ramayan he says that Ravan was a kind-hearted man – he would punish the Brahmins only when he caught them carrying out yagyas or consuming alcohol. It is necessary to clarify here that drinking was an addiction among Devtas and Brahmins. Because of their fondness for drinking (surapan) they came to be regarded as Surs and those who eschewed drinking like Ravan became Asurs. The evidence of this behaviour is available in the Ramayan.

According to Periyar, ten heads of Ravan stand for an equal number of virtues he possessed: (1) great intellectual, (2) great saint, (3) scholar of the Vedas and Shastras, (4) kind-hearted provider for his kins and his subjects, (5) brave general, (6) powerful man, (7) valiant soldier, (8) pure soul, (9) favourite son of god, and (10) generous man.

Was Sita the daughter of Ravan?

Different versions of the story of Ram abound and so do the theories. On 14 October 1962, Lucknow daily Navjivan published an article in a weekly supplement, which, referring to a Kashmiri work Prakash Ramayan, said that Sita was Ravan’s daughter. According to this article, “Ravan had married an apsara [beautiful woman and accomplished dancer] named Mandodari. She gave birth to a girl child. Ravan was not around when the girl was born. An astrologer predicted that the girl would bring misfortune to the clan. An apprehensive Mandodari had the baby tied to a stone and had her thrown into the river. But the baby didn’t drown; she was carried far away by the water currents and got stuck on the bank. Fortunately, King Janak found her. He adopted her and brought her up with great love and care.”

Jigyasu observes that the story of an apsara called Mandodari doesn’t appear credible. He further writes, “Some other purana, perhaps Padma Purana, also says that Sita was Ravan’s daughter, and she was born to Mandodari. However, Mandodari was not an apsara, but the daughter of Maydanav. Ravan knew Maydanav well and he used to frequent his house. Mandodari fell in love with him. Sita was born out of wedlock, and out of shame Mandodari kept her in a pot of ghee and left it in a field. King Janak found her and brought her up. Though Maydanav lived in Meerut, because he was a Shaivite, he used to visit Janak, also a Shaivite (the bow of Shiva was kept in Janak’s house). Once Maydanav took his daughter Mandodari to Mithila, where she gave birth to a girl child and out of shame he had the child put away in the field. Later, when he learnt of her love for Ravan, Maydanav had her married to Ravan.”

Jigyasu writes: “Mandodari falling in love with Ravan at a tender age appears natural, and Sita’s resemblance to Mandodari also lends credibility to the theory of Sita being Mandodari’s daughter. And Ravan’s conduct towards Sita and Sita’s behaviour with Ravan also strengthens the theory of their father-daughter relationship.”

A new story of Lankavatar Sutra

Acharya Narendra Dev, in his voluminous work Bauddha Dharma Darshan, has mentioned “Lankavatar Sutra”. “Lankavatar Sutra” means “preaching of righteous path of religion to Ravan, the king of Lanka”. This is a new theory, which states that Buddha explained the righteous path to Ravan. Acharya Narendra Dev has also said that “Lankavatar Sutra” has been translated three times into Chinese: by Gunabhadra in 443 AD, Bodhiruchi in 513 AD and Shikshanand in 700-704. Bunyiyu Nanjio of Kyoto, Japan, edited the text in 1923. Dr Suzuki has also produced a scholarly text on it. This text contains 10 large fascicles. First fascicle contains the conversation between Ravan and the Buddha. Other fascicles contain answers given by the Buddha to Ravan. This is the massive, fundamental text of the Mahayan path’s scientism.

Jigyasu writes in his conclusion that naming the title of this work after Ravan and Ravan himself seeking answers to his queries from Buddha leaves no doubt that Ravan was a non-violent, religious, wise intellectual and a noble Buddhist. He was contemporary of Buddha and received religious teachings from Buddha. Referring to this “Sutra”, Jigyasu shares another piece of information. He writes: “It is also learnt from the 10th fascicle of ‘Lankavatar Sutra’ that characters of brahmanical literature like Vyas, Kanad, Kapil, Panini, Brihaspati, Yagyavalakya, Katyayan and Ashvalayan came into existence chronologically after Buddha, and Ramayan, Mahabharat, Gita, Ram and Kaurav-Pandav also came much after the Buddha. Bali, Sugriv, Hanuman, Jambvaan and many other monkeys and bears were a creation of the ingenuous Ramayan authors. With Lankavatar Sutra coming to light everything stands exposed – the gold of brahmanical mind turned out to be mere brass – that deceitful imagination densely clouding the mind was blown away by the speedy wind currents of Lankavatar Sutra and the true blue sky shone brightly before the eyes.”

He further writes: “If some Brahman scholar or proponent of brahmanical literature says that Lankavatar Sutra is a fake book, or the tenth fascicle of Lankavatar Sutra is a later addition, and Ravan and Ram were born much earlier in the Treta Yug and Gautam Buddha was born in Kaliyug, then their argument is rendered completely meaningless by Sanskrit-language scholar Valmiki’s Ramayan in shloka 34 section 109 of chapter ‘Ayodhya Kaand’. Here, opposing the atheists, Shri Ramchandraji tells Jaabaali, ‘Just as a thief is punishable, similarly anti-vedic Buddha is also punishable. Tathagat Buddha and an atheist should be put in the same category.’

“In other words,

Yath hi chor: Sa tatha Buddhwasthagat Nastikmatra Viddhi

Tasmaddhi: Shakyatam: Prajana Sa Nastike Nabhimukhu Buddh; Syat.”

Translation: Parmanand Baiga; copy-editing: Anil

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History