A poem by Om Prakash Valmiki (in translation) reads: “Caste is the razor-sharp instrument of the primitive civilization which riddles the body of the man on the street.” The film Article 15 portrays the thorniness of the caste system. It documents inequality, discrimination and exclusion that are the hallmarks of the caste system. At a time when the leading lights of the world of literature and the arts – especially the performing arts – slip into silence whenever the issue of caste is broached, it warrants some courage to produce a work that has the question of caste as its peg. Filmmaker Anubhav Sinha is known for taking the uncharted path and his last film Mulk is testimony to it.

There are two songs in the first half of the film – one that accompanies a performance and the other that plays in the background. The first song is in Bhojpuri: “Kahab to lag jayee dhak se, bade-bade logan ke bangla do bangle, aur bhaiyaa ac alag se, alag se.” It is no secret that economic inequality is growing deeper and wider in India. The World Inequality Lab Report, authored by economist Thomas Piketty and others, underlines this fact. The song describes the aspirations, the pains, the sadness, the misery and the struggle of the Dalits and the oppressed in the rural areas.

There are two songs in the first half of the film – one that accompanies a performance and the other that plays in the background. The first song is in Bhojpuri: “Kahab to lag jayee dhak se, bade-bade logan ke bangla do bangle, aur bhaiyaa ac alag se, alag se.” It is no secret that economic inequality is growing deeper and wider in India. The World Inequality Lab Report, authored by economist Thomas Piketty and others, underlines this fact. The song describes the aspirations, the pains, the sadness, the misery and the struggle of the Dalits and the oppressed in the rural areas.

The other song that plays in the background is Blowing in the Wind, by Bob Dylan, a Nobel prizewinner for literature. The song stands up for human rights and decries war and war hysteria. “Yes, and how many ears must one man have before he can hear people cry? Yes, and how many deaths will it take till he knows that too many people have died?” goes a verse of the song. We see caste-based discrimination all around us. “Ignited minds” like Payal Tadwi and Rohith Vemula are forced to commit suicide; Dalits are targeted in the name of the holy cow and the Adivasis are sacrificed on the altar of “development”. But we hide ourselves under a cloak of silence. The film also quotes some portions from Rohith Vemula’s suicide note.

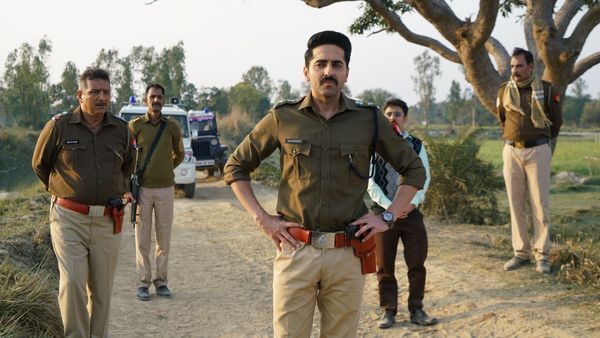

The film’s protagonist Ayan Ranjan, a role essayed by Ayushmann Khurrana, is a young IPS probationer, who is posted at a remote rural area of Uttar Pradesh. On the very day he takes up his assignment, two Dalit girls are raped and found hanging dead from a tree. A third girl goes missing. It is the for the first time that Ayan, brought up and educated in cities in India and abroad, comes face to face with the brutal reality of rural India. It is a culture shock to him. And the scene shakes the audience to the core.

As soon as we think of “they” and “us”, we become part of social exclusion, so rampant in rural parts of the country. The film excellently portrays the dichotomy of “they” and “us”; it shows how discriminatory practices are still alive and kicking. Here “us” is the upper-caste, educated men from well-off families and “they” are the people living on the margins of society.

The rapists include the Jat bodyguard of Ayan and the local Brahmin SHO (policeman in charge of a police station). The entire administrative machinery is out to hush up the case and the father of the girls is framed in their murder. The film details the saga of the struggles of the Dalits.

Symbols and images have been used with great finesse in the film, reminding one of Tulsi Ram’s autobiographical Murdahiyaand Sharad Kumar Limbale’s story Dalit Brahmin.The film’s scriptwriter Gaurav Solanki has produced a gripping tale and the crafted dialogues that help visualize. One of them is, “Sometimes we become ‘saravjan’ and sometimes ‘bahujan’ but never ‘jan’.” It is a stinging jibe at the identity-based politics. This brand of politics took the Hindi belt, especially Uttar Pradesh, by storm, and its practitioners were in power for almost 25 years. And yet, no durable social change came about. Of course, the political empowerment of the Dalits and the Backwards was in itself a “silent revolution” and that is no mean achievement.

Which face of societal truth an artiste wants to present through their work, depends on their wisdom and understanding and is entirely their choice and privilege. Having said that, Article 15 gives the impression that casteism is a scourge that afflicts only the rural hinterland. This is far from the truth. Untouchability and discrimination are as much an urban reality, though they manifest themselves in a different way. According to the India Human Development Survey, one out of every four urban Indian practises untouchability in one form or the other.

The film also sends out a subtle message that the Dalits and the other oppressed need an emancipator from the upper castes. In his book Burden of Democracy, Pratap Bhanu Mehta argues that the upper caste reformers/emancipators do what they do to maintain the “balance” among the Hindus while the reformers from the oppressed classes work for genuine emancipation. Through the Bhim Army, the film does try to convey the message that Dalits will need to struggle for their own emancipation. In one scene, Ayan’s girlfriend tells him: “We do not need heroes. We need people who do not wait for the heroes.” Society doesn’t need messiahs; its emancipators will come from within. The marginalized will emancipate themselves.