According to oral narratives based on the Ramayana, Janak, the king of Mithila, ordered the women of Mithila to paint the whole kingdom on the occasion of the marriage of his daughter Sita to Ram. The women painted the walls of their homes with cow dung and natural colours. However, these narratives are silent about the caste of women painters.

In the early 1960s, Bihar experienced a severe drought resulting in widespread hunger and poverty. The Bihar government launched a relief programme to provide the marginalized population with livelihoods other than agriculture. As part of this programme, the state government awarded Bombay-based artist Bhaskar Kulkarni a grant of Rs 50,000.

Bhaskar Kulkarni travelled to the different regions of Bihar. At Jitwarpur village, in the southeast of Madhubani district, he found mud walls painted with natural colours depicting folklore. Realizing the beauty of this art, Kulkarni encouraged the women of the village to paint on paper. The creations of these village women were exhibited in the Industrial Exhibition held in New Delhi in 1962. The paintings were sold at Rs 5 to Rs 35 each. The art thus took a commercial form, and women of the village got an opportunity to showcase their talent. Nevertheless, a question still remained: Did women from all communities get equal opportunity to showcase their talent and be involved in the business?

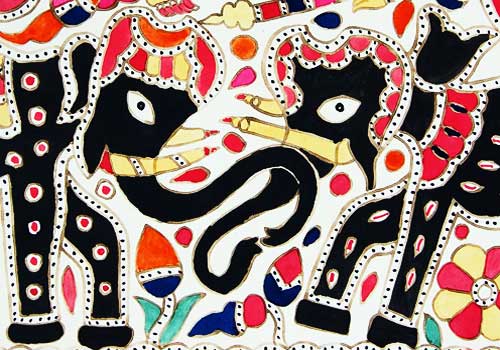

In his article The Narrative Paintings of India’s Jitwarpuri Women [Woman’s Art Journal, Vol 11, No 1 (Spring-Summer 1990)], Jagdish J. Chavda writes that generally women of the Brahmin, Kayastha and Dusadh communities are involved in the business of Madhubani painting. The Brahmin and Kayastha women execute their art in a precise, formal manner. Their art depicts the images of Durga, Kali and Ganesha, and also tells the stories of Ram and Sita’s and Shiv and Parvati’s marriages. On the other hand, the “Harijani” paintings are painted by women from Dalit and other backward castes, most of whom are Dusadhs. Their art is more earthly. It ranges from themes like women cooking in the kitchen to images of goats, elephants, peacocks and other animals. These women have also started painting their own caste deities like King Sahlesh and Rahu-ketu. Did these women themselves decide to not paint Hindu gods and goddesses or were they prohibited to do so because of their caste?

From housewife to painter

Shanti Devi is a national awardee Madhubani painter hailing from the Dusadh caste of Mithila region. In her interview with Folkartopedia, she discusses her journey as a painter. Because she was born into a Dalit family, she says, initially, she didn’t attend school. Seeing girls from upper-caste communities go to school, her desire to get an education arose. Her mother was a farm labourer. She did not have money to educate her daughter. Moreover, her mother feared the societal norms that barred Dalits from getting an education.

Shanti Devi did end up going to school, but she faced casteism. Her teachers practised untouchability and made her sit separately in the class. Casteist slurs by her upper-caste teachers were common. Despite all the difficulties she faced, she completed her matriculation. She got married when she was about 15 years old. Her husband’s family didn’t have a proper house to stay in or enough food to eat.

Shanti Devi has seen her mother make paintings on the walls of her home. In fact, her father-in-law was also a painter but she never knew she could earn a living by making these paintings. It never even crossed her mind that she would become a professional painter one day.

Her paintings were never recognized in her village, Laheriaganj. Art was the monopoly of the upper castes. It took an American researcher who had come to the village to recognize her talent and encourage her.

Why has she chosen this particular subgenre of Madhubani painting? She says that Dalits were not allowed to paint the Hindu gods and goddesses. She narrates an incident in which an old Brahmin man threatened her and her husband with consequences if she continued painting the images of Kali, Durga, Shiva and Parvati. That is when she started painting the flora and fauna of the village. Later, she decided to paint the story of their own caste deities Raja Sahlesh, Macharkand and Maina Sati.

Shanti Devi says that whenever anyone comes to the village inquiring about Madhubani art, the upper-caste people always direct them to the upper-caste painters. Dalits are thus denied opportunity to promote their art.

Shanti Devi returned her national award to the President saying, “I do not have a house to keep this award, then what is the use of award for me?” Taken aback, the central government provided her a sum of Rs 62,000 to build her house. The upper-caste people of her village were jealous and created several obstacles while her house was being built.

Shanti Devi’s story tells us that casteism is present in the art. “People still practise untouchability, and the opportunities of Dalits are always taken away by the upper castes,” says Shanti Devi. She is angry about the fact that several Madhubani painting exhibitions were organized by the government as early as the 1980s, yet the government officials never made an effort to reach out to the illiterate Dalits who could not read the advertisements.

From labourer to painter

Dulari Devi relates her struggles in an interview with SyracuseArtsSciences channel. She is a Madhubani painter hailing from the Machuwara caste [fisherfolk community categorized as an Extremely Backward Caste (EBC)]. She used to work as a maid in the house of an upper-caste painter. When she saw the young women painters of the house, she also wanted to be one of them. However, it would be a while before she could gather the courage to tell her employer that she wanted to study art in an art centre. While she got admission and learnt painting, she couldn’t have done it on her own. She needed the patronage of wealthy upper-caste people to become an artist.

Dulari Devi is now a master painter and instructor at the Mithila Art Institute. She received the State of Bihar Award for Excellence in Art in 2013, and authored the first autobiography by a Mithila painter, the award-winning, Following My Paintbrush (Tara Books, 2010).

As it is evident from the stories of Dulari Devi and Shanti Devi, the Dalits and the other backward castes lack the opportunity to take up art as a livelihood. While the upper-caste women have been the traditional Madhubani painters, the women of the Dalit and other backward castes have had to fight both caste and gender norms to be in the business. These women faced financial constraints while starting a business and the dominance of Brahmins and Kayasthas in the field didn’t allow their business to grow.

Today, many women from Dalit and other backward castes are following in the footsteps of Shanti Devi and Dulari Devi and aspiring to become Madhubani painters. This new form of Madhubani painting is no longer just an art but a means of empowerment. Dalit and EBC women can dream of participating in the greatest exhibitions abroad and getting worldwide recognition. They have appealed to the state and central governments for support and recognition because mere awards will not fill their empty stomachs.

Editing: Goldy/Anil

Updated on 21 September 2020. ‘Folkartopedia’ was earlier misspelt. It has been corrected.

orward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of the Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) community’s literature, culture, society and culture. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)