Sanjay Kumar: The next decade belongs to EBCs

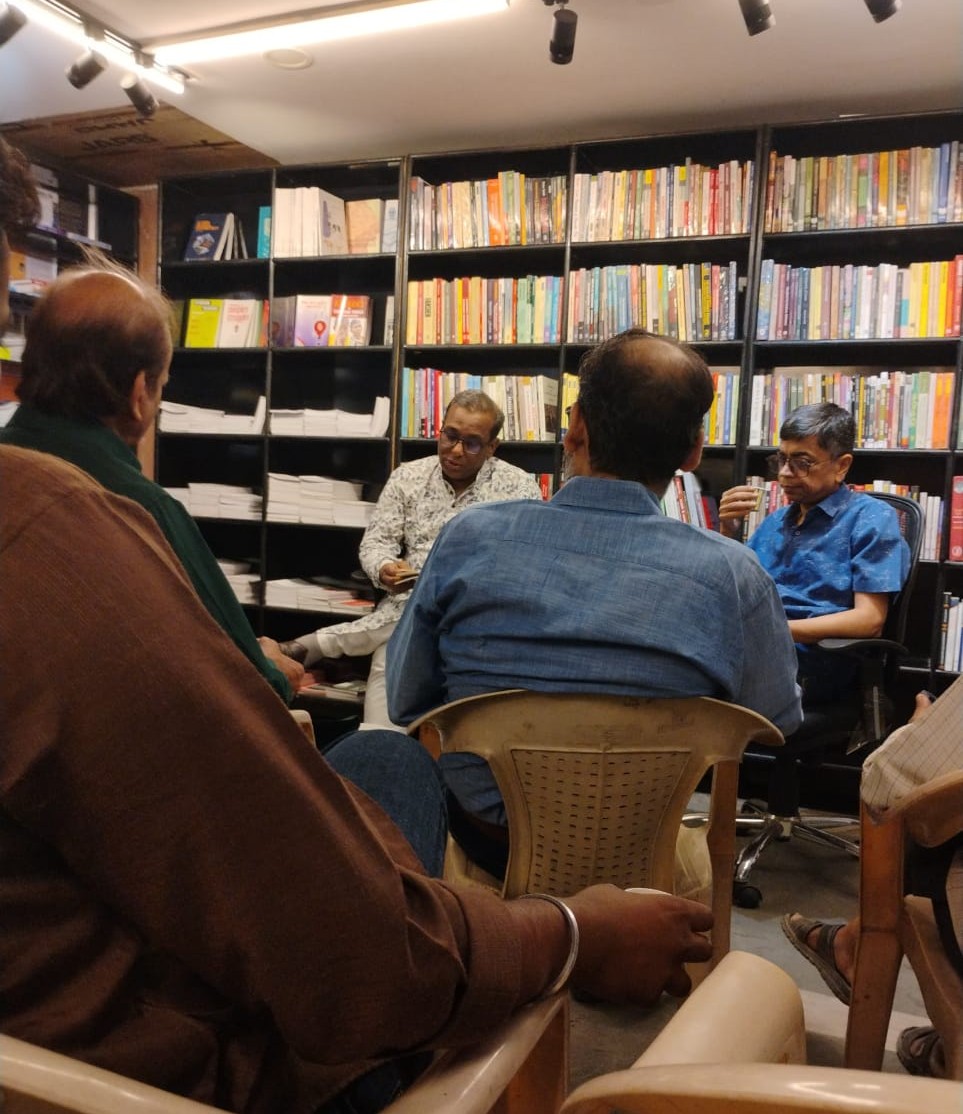

In his book Bihar ki Chunavi Rajniti: Jati-Varg ka Samikaran (1990-2015), Prof Sanjay Kumar, director, Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), has dwelt on the social and political changes that informed successive elections in Bihar. In an interview with Nawal Kishore Kumar, Hindi Editor of FORWARD Press, he talked about the upcoming assembly elections in Bihar and the present political situation in the country. He said that caste politics should not be seen in a bad light and that it is not confined to Uttar Pradesh and Bihar either. He also shared his thoughts on national politics in the days to come.

From a layman’s perspective, what is psephology about?

Psephology is the science of making predictions on the outcome of elections before polling. It tells you which party is likely to win how many seats and which party or alliance will win. This is what psephology means for a common voter. However, it makes no prediction about how many votes a party will garner and the average voter is not interested in it either.

Exit polls also do the same. Then how are they different from psephology?

What I said earlier was from the perspective of the common voter. But a psephologist is not merely an astrologer who predicts the seat tally of different parties. Psephology is more than that. As you said, exit polls are held just before the announcement of the election results. But you must have also seen that surveys are conducted before voting to see who is going to win or lose. Psephology also has a role to play in this exercise. Psephology is about finding out the trend or pattern in voting. For example, a survey can be conducted before the Bihar elections to find out what are the expectations of the people from different parties, what is the public mood, which issues are the parties raising before the voters and so on. This is also psephology. It is also about making projections, say, three months before the voting, to find out which way the wind is blowing, what are the factors that can change the fortunes of a party, etc. Thus, psephology is less about predicting results and more about gauging trends and patterns.

What led you to writing the book Bihar ki Chunavi Rajniti: Jati-Varg ka Samikaran (1990-2015)?

For the past 25 years, I have been basically studying only elections. I have conducted studies and written articles on other issues but they have also been related to elections in one way or the other. I have done a study on the youth – on their socio-economic problems, their outlook and their concerns. But I also studied how interested they are in elections and whether they want to participate in them. Around the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, we conducted a study on what women voters think and why women are coming out in much larger numbers than earlier to cast their votes. While I had been writing articles and commentaries on elections in other states, I began writing the book on Bihar, Bihar ki Chunavi Rajniti: Jati-Varg Ka Samikaran (1990-2015), in 1995. I have closely studied almost all elections in Bihar. I wrote analytical articles both in Hindi and English on elections before voting and after announcement of results. I come from Bihar and I thought to myself, ‘If I am analyzing elections throughout the country why not begin from my own state!’ That was how I analyzed the elections from 1990 to 2015 in Bihar and compiled the analyses in the form of a book. The book tells you about the changes that have come about in Bihar since 1990. My Bihari background was an additional source of inspiration. Being from the state I have a deeper understanding of the politics of Bihar. I wanted to contribute academically to my state and that is why I decided to write the book.

Whenever anyone talks about politics in Bihar, the discussion invariably veers towards how caste equations play an important role there. Are other states like Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh different in this respect?

Nowadays, we see caste politics in a bad light. It is said that elections in India are caste-based and that the issues don’t really matter to the voters. Bihar and Uttar Pradesh are considered synonymous with caste politics and it is believed that caste plays little or no role in economically developed states like Karnataka, Kerala and Andhra Pradesh. Caste politics is considered an indicator of the backwardness of a state. The fact is that there is no state and voter to whom caste is not important. There is caste politics in all states. The only difference is that in some states it plays a bigger role and in other states a marginal role. In some states, upper castes come together around a particular caste. In other states, lower castes come together against the upper castes. A new situation developed in Bihar after the 1990s. In my book, I have focused on the post-Mandal phase. After the implementation of the Mandal Commission recommendations, all castes closed ranks. Earlier, the upper castes used to be united and wielded quite an influence. But after Mandal, many more castes, especially castes which had little representation in politics – I am talking of the lower castes – became united. Thus began the struggles of different caste groups for grabbing power. The underpinning of this struggle was that if one’s caste has a bigger population it should have a greater share in power. That led to the building of the perception that caste politics is confined to Bihar whereas the truth is that it is very much present in other states. In states like Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, the upper castes are united while the middle and lower castes are not that politically conscious – they are not as united as they are in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

You talked about the post-Mandal phase. This phase witnessed the backward classes closing ranks. They united not only for electoral purposes but also at the social level. You say in your book that the rise of political consciousness among the Backwards had begun way back in the 1960s. Then, why did it take so long to make an impact?

You see, the 1970s and the 1980s also saw growing representation of the OBCs in politics. The Socialist Party emerged. But the OBCs were basically playing a secondary role. They played second fiddle to the mainstream political parties. The Socialist Party did not command much influence. But post-Mandal, new parties like the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) and the Janata Dal United (JDU) emerged. The OBCs considered these parties as their own. They came forward to strengthen them. The OBCs were the core support base of these parties. The same is true of the parties of Upendra Kushwaha and Mukesh Sahni. In the 1960s and the 1970s, the OBC leaders began mobilizing the backward castes. But they were not strong enough to float their own parties. They worked in tandem with the mainstream parties. By the 1990s, in the post-Mandal phase, their unity had become very strong and they had realized that they had the numbers. Their share in the parties became huge.

Dr Ram Manohar Lohia had said, ‘Picchde pave sau mein sath’ (Let the backwards get 60 out of 100) and Jagdev Prasad or some other revolutionary had said ‘Nabbe par das ka shasan nahin chalega’ (The rule of 10 over 90 won’t work). So, was that just a beginning?

Yes, these slogans were coined and they gained currency in the 1960s and 1970s. But they were just slogans. It was not that they did not have the numbers then. The numbers were always there. It was not as if the OBCs had a smaller share in the population at that time and it had suddenly grown by the 1990s. Numerically, they were always stronger than the upper castes. After the implementation of the Mandal Commission report in the 1990s, leaders like Lalu Prasad and Nitish Kumar burst on the scene. They launched a movement focused on the OBCs.

In your book, you have very lucidly explained how politics changed in Bihar from one election to the next. Did the issues also change?

The core issues remained the same but the side issues kept on changing. But then issues may change from one constituency to another. In the same election, voters of a constituency may consider a certain issue to be important while another issue may be the most important in another constituency. The issue of social justice was a constant theme in all the elections since the 1990s. But the definition of “development” was different for different people. In one constituency, development may mean power and water, and in another, it may be roads. In fact, development may mean different things for people of different villages in the same constituency. So, the core issues remained the same but the side issues, the supplementary ones, kept changing.

Also read: Bihar’s electoral politics: The caste-class equation (1990-2015)

The post-Mandal era witnessed rapid changes in the political scene in Bihar. The upper castes that ruled the roost in the state from 1950 to 1980 have been pushed far away from the centres of power after the implementation of the Mandal Commission report. Has this happened only because of changed political equations or is there something more to it?

Numbers matter a lot in elections. There is no doubt that the number of upper castes in positions of power in the state now is much less than earlier. However, like the Dalits, the OBCs as a whole and the different castes of OBCs, the upper castes, too, have closed ranks. But what is important is that all political parties have come to realize that if they have to form their governments in states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, they will have to project a pro-social-justice face. Dalits and OBCs form a majority of the population in Bihar, due to which for the past 25-30 years, all parties have been forced to project a Dalit or an OBC as their leader. That is why the upper caste leaders have been relegated to the second row. I feel that this will continue. Almost all the parties have upper-caste leaders, too. They will continue to have a share in the party positions. But the parties will have to think twice before installing them at the very top (as chief minister or deputy chief minister). I don’t think any party can afford to contest elections with an upper-caste face or offer them top positions. If any party does that, it is unlikely to succeed. The parties want to project themselves as flag-bearers of social justice. It is highly unlikely that the upper castes who called the shots in the politics of Bihar from 1960s to 1980s will ever regain their position.

The term EBC (Extremely Backward Classes) has acquired a prominent place in the political lexicon of Bihar. When, in 1979, the then Karpoori Thakur government implemented the recommendations of the Mungerilal Commission, it had led to a ferment among the EBCs. Since 2005, the EBCs have been in a decisive position. It seems an upper OBC-versus-EBC tussle has begun. Your take?

This is not happening only in Bihar. In the 1990s, after the implementation of the Mandal Commission report, OBCs were the talk of the town. However, the context has changed over the past five-odd years. Now, we are talking of upper OBCs and lower OBC. The parties are well aware of the importance of this distinction. If you study the politics of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and other states you will realize that the upper OBCs have been supporting specific parties in different states. For the past 30 years, Yadavs have been backing the RJD in Bihar and the Kurmis have been siding with the JDU. This situation remains unchanged. As a result, the other OBC castes have started feeling that the politics in the name of the OBCs has yielded nothing to them. That is why we can see schisms in the ranks of the OBCs. In Uttar Pradesh, too, one can see a clear distinction between the politics of the upper and the lower OBCs. The new parties that have emerged in Bihar over the past five to seven years are not led by the upper OBCs. They all come from the lower OBC castes. This is a major change in the politics of the state.

Your book also talks about Pasmanda Muslims. You have used tables to show the role they have played in the politics of Bihar post 1990. What is the place of Pasmanda Muslims in the politics of Bihar?

If we talk of the past 10 years, there has been no change in the status of the Pasmandas. Given the political matrix of Bihar, Muslims, both Pasmandas and Ashrafs, have not had many options. Two parties – JDU and LJP (Lok Janshakti Party) – are in alliance with the Bharatiya Janata Party. They were together in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections and they will be contesting the assembly elections together. The other alliance will take shape around the RJD. It will include many small parties. Looking at the choices and the preferences of the Muslim voters in the last election, it is unlikely that they will vote for the BJP or the NDA (National Democratic Alliance) this time. Whether they are angry or not, whether they are getting their due share or not, they have to vote for alliances like the UPA (United Progressive Alliance). It is because of this lack of alternatives that there has been no change in the social, political and economic status of the Pasmandas over the past five-ten years.

In your book, you have described how the EBCs voted en masse for Lalu Prasad in the 1995 elections and how his appeal faded with time – so much that Lalu voters started backing Nitish Kumar. But in the elections held after 2010, we saw the emergence of a new phenomenon – of EBC votes shifting to the BJP. Have the EBCs lost faith in Nitish Kumar?

There was a time when the BJP got only upper-caste (including Vaishya) votes. But subsequently, the EBCs started siding with it in a big way. In the 2004 and 2009 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP did not do well. But still its core popular base, ie the upper castes, remained intact. The BJP realized that OBCs are not homogenous and that the upper OBCs have been voting for particular political parties and that it would be very difficult for it to persuade them to switch sides. The Yadavs, the Kurmis and the Koeris have been traditionally supporting different parties. The BJP’s political strategists decided to exploit the upper-lower binary among the OBCs. Instead of working to garner support from the upper OBCs, it decided to focus on EBCs and other similar castes. It made a determined effort to breach the OBC citadel and nominated many EBCs as its candidates. The party could gauge that the EBC voters are not happy with the kind of politics Lalu Prasad and Nitish Kumar had been playing for the past 25-30 years. They were unhappy that they did not get their due share in OBC politics. The BJP exploited this sentiment. It began wooing the EBCs, and statistics show that in the 2014 and 2019 elections, a big chunk of the EBC voters backed the BJP. The same thing happened in Uttar Pradesh. Figures show that in that state, too, the EBCs in huge numbers sided with the BJP.

If the OBC reservation quota is sub-categorized, would it have a long-term impact on national politics?

If the OBCs were to be sub-categorized and the EBC started getting reservations in proportion to their population, the party instrumental in bringing about this change would benefit. The BJP is already garnering a fair chunk of the EBC votes in many states. So, if the BJP government takes an initiative in this direction, it won’t benefit much for the simple reason that it already enjoys the support of the EBCs. I feel that if the OBCs are sub-categorized and the OBC reservation quota is subdivided, it is unlikely to bring about any major political change because the BJP has already cornered the EBC voters.

In your book, you have talked about what shape politics will take in the future. Please throw some light on it for our readers.

Politics is changing rapidly in the country and so making any guesses about the future is not easy. But as far as Bihar politics goes, OBCs will continue to be a major factor in the next 10-15 or even 20 years. Both upper and lower OBCs will play important roles. Parties may come and go but they will have to ensure that the OBCs get their share. The chances of success of any party that does not do so will be very low. Secondly, parties doing politics in the name of OBCs will have to accord the lower OBCs their due place. Otherwise, the lower EBCs will form scores of caste-based parties and that will turn elections multi-polar and lead to fractured mandates. Parties that want to succeed in Bihar will have to accommodate the OBCs and especially lower OBCs. I feel this is the direction politics will take in Bihar, and the parties also know this. They know that they will have to move in that direction if they want to make their mark. The political scene will be similar in other Hindi-speaking states. We have been focusing a lot on Dalit politics and OBC politics. Now, we will have to turn our focus on EBCs. They will continue to be central to politics for at least the next 15 years.

(Translation: Amrish Herdenia; Copy-editing: Anil)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History