To qualify as a classic, a novel has to creatively mirror the core reality of its times. Marx and Engels used to tell their friends that if they wanted to understand the rise of capitalism in France they should read novels of Balzac instead of poring over the dreary accounts of economic historians. Marx wrote that he owes his knowledge of the history of France more to Balzac’s works and less to the writings of the French chroniclers.

Godan, by Premchand (31 July 1880 – 8 October 1936), is an internationally renowned novel that depicts the core reality of contemporary society. The novel underlines the fact that social, religious, economic and political relations in Indian society were governed by the varna-caste system and that though the British were ruling the country, it was the upper castes that called the shots in the social and economic spheres and wielded the real power on the ground. It also shows how a coalition of upper castes was trying to wrest political power from the hands of the British in the name of Swaraj. The social reality that finds expression in Premchand’s Godan in 1936, had been presented by Ambedkar in his writings since 1917. It is a coincidence that Ambedkar’s The Annihilation of Caste and Premchand’s Godan – two works of different genres underlining the fact that the varna-caste system was the pivot of India society – were published in the same year, 1936.

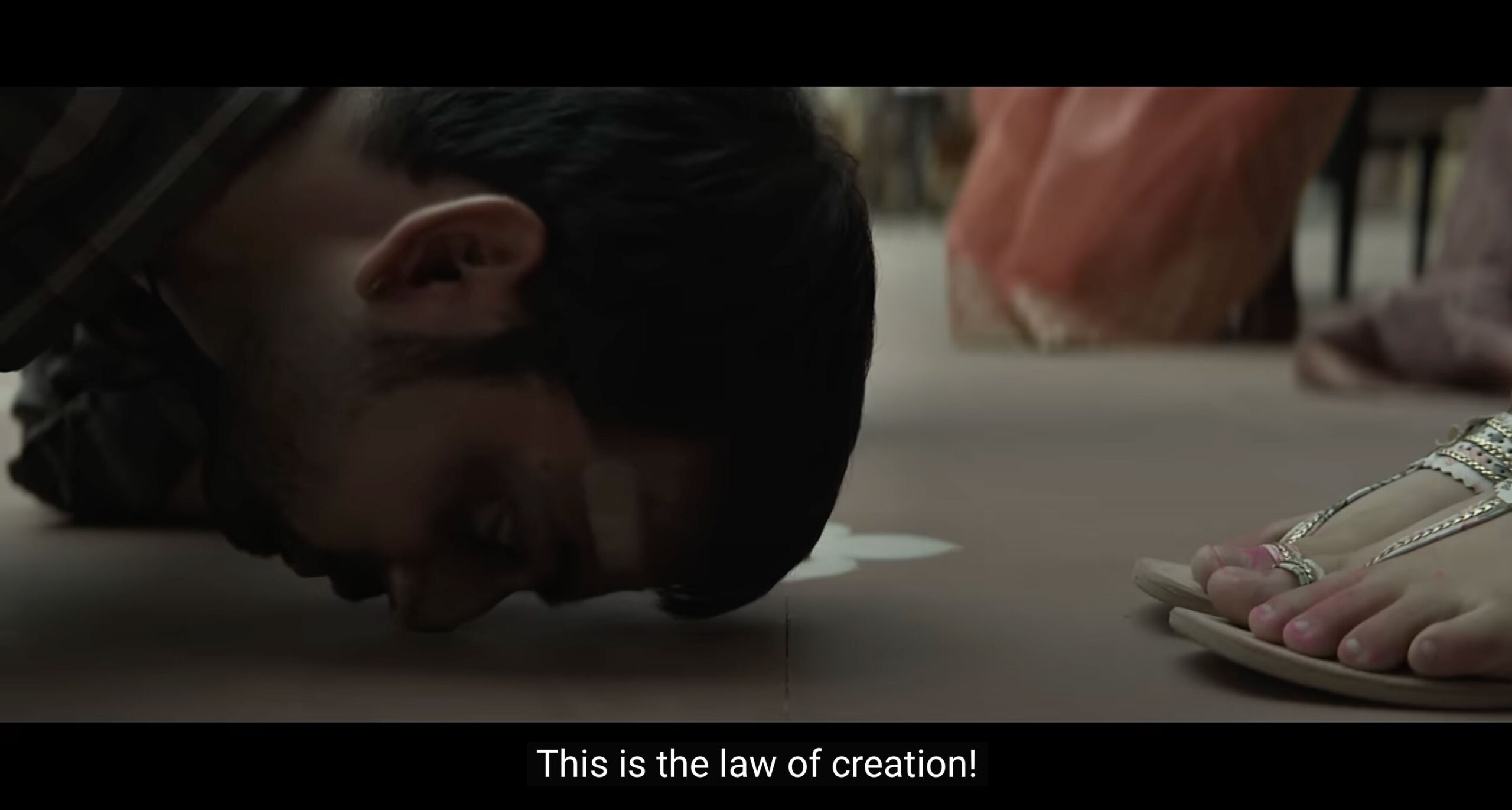

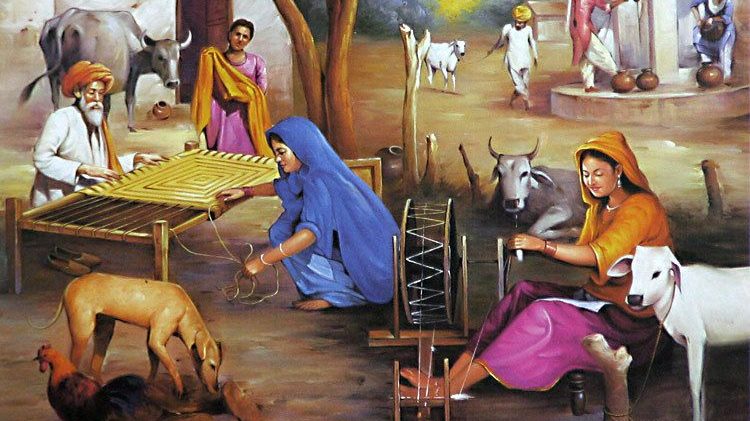

In his novel, Premchand shows how the upper castes were an unproductive and parasitic class, living off the labour of the backward and Dalit castes. He also portrays the Backwards and the Dalits as productive and toiler communities. Godan’s lead protagonist Hori Mahto and his family’s back-breaking toil is a case in point. Godan opens with the following lines: “After giving fodder and water to the bullocks, Hori Mahto told his wife Dhania – send Gobar to turn the soil in the sugarcane field. I don’t know when I will return. Just pass me my stick. Dhania’s hands were full of cow dung. She was making cow-dung cakes.” After a couple of pages comes the description of the hard toil of Hori’s son Gobar and his daughters. “When Hori reached near his village he found Gobar was still turning the soil and both the girls were working with him. Loo was blowing, gusts of blistering air were rising and the ground was blazing. It was as if nature had infused fire into the air. Why are they still working? Do they want to sacrifice their life for the sake of work?” He turned towards the field and shouted from a distance, “Why don’t you come back Gobar? How long will you continue working? It is past noon. Don’t you understand?”

Also read: Premchand’s farmer, backward classes and Indian culture

Without exception, all the upper-caste characters of Godan are unproductive and parasitical and all the backward and Dalit characters are productive and are toilers. But while the parasitic classes are living in the lap of luxury, the toiler castes are condemned to a life of poverty and misery. Premchand does not forget to pinpoint the cause for this state of affairs. Through the narrative, he makes it clear that the fruits of the labour of the toiler backward and Dalit castes are usurped by the upper castes and that the British Empire is also a beneficiary of this loot.

The conduct of the characters of Godan clearly shows that the members of the unproductive, parasitic classes are basically cruel and heartless. They are hypocrites and conspirators. This is apparent from all the characters representing the upper castes, namely Pandir Datadeen, Jhinguri Singh, Pateshwari Lal, Rai Saheb, Omkarnath Shukla and Tankha. In contrast, the toilers like Hori, Dhania, Bhola and Silia are full of compassion and humanity.

Godan’s plot revolves around two villages – Belari and Semri. At the time when Godan was written, the British were ruling India but the two villages were under the control of the upper castes, who were effectively the rulers, and the backward castes and Untouchables were at their mercy. Premchand ensures that the readers understand this situation. Pandit Datadeen, Jhinguri Singh, Pateshwari Lal and Sahuain are the de facto rulers of Hori’s village Belari. Pandit Datadeen not only wields religious power but also owns agricultural land, besides being a moneylender. Jhinguri Singh is a farmer who owns large tracts of fields while Pateshwari Lal is the patwari. Sahuain runs a shop and also lends money on interest. Hori, his family and in fact the entire village are the victims of the exploitation, oppression and conspiracies of Brahmin Datadeen, Thakur Jhinguri Singh and Kayastha Pateshwarilal, who, as the patwari, is a government functionary. Premchand describes Pateshwarilal’s character thus: “As he was the patwari, he used to get his fields ploughed without paying any wages; he used to get his crops watered without paying any wages and he used to make money by pitting the farmers against each other. The entire village feared him.” Pandit Datadeen and Jhinguri Singh were, more or less, in the same mould.

Rai Saheb lives in Semri, five miles away from Belari. He is the landlord who collects rent, extracts unpaid labour from people and extorts money from farmers. At the same time, he is also a soldier in Gandhi’s struggle for Swaraj. He has been to the jail once or twice. His friends are journalist Omkarnath Shukla, lawyer Shyam Bihari Tankha and Professor Mehta. It is clear from their names that they all are upper-caste. Here’s a glimpse of how Premchand draws up their characters: “A motorcar pulled up at the main gate and three gentlemen got down from it. The one wearing khadi kurta and chappals is Pandit Omkarnath. He is the celebrated editor of the daily newspaper ‘Bijli’ and has lost considerable weight worrying for the country. The second gentleman, wearing a coat and pants, is a lawyer. Being briefless he works as a tout for an insurance company. He makes much more than he would have from legal practice, by helping landlords secure loans from mahajans [moneylenders] and banks. His name is Shyam Bihari Tankha. The third gentleman, wearing a tight pajama and silk achkan, is Mr B. Mehta, a professor of philosophy in the university.” Premchand hints that Rai Saheb and the three others would be ruling the roost in India of the future (after independence). They are unproductive parasites, riding on the backs of the working class.

The rural oppressors and exploiters Pandit Datadeen, Jhinguri Singh and Pateshwari Lal have links with Rai Saheb, Omkarnath Shukla and Tankha. Premchand alludes to the fact that this nexus would be the ruling class of post-Independence India. He also does not forget to tell his readers that this nexus would not do anything to benefit the toilers like Hori, Dhania, Heera, Bhola and Siliya.

The varna-caste system is the pivot of Indian society and controls the caste, class, community and even personal relations of Indians. A powerful and telling delineation of this theme makes Godan a representative novel of the cow belt.

(Translation: Amrish Herdenia; copy-editing: Anil)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History