On 9 May 2021, I was at the Shringverpur Ghat in Prayagraj (Allahabad), Uttar Pradesh, for the last rites of my maternal grandfather, Amarnath Tiwari. I could see dozens of bodies being cremated on the banks. I could also see that many more were buried in the sand. My guess is that their total number must be upwards of 5,000. The spots where the bodies were buried were ringed by pieces of bamboo driven vertically into the sand and covered by shrouds. The shrouds looked new, indicating that the burial was done recently – maybe 2-3 days ago or at the most 5-10 days ago.

Cremations are carried out in many ghats in Prayagraj, including Jhunsi, Chhatnag, Daraganj (Dashashamev), Arail, Rasoolabad, Fafamau and Shringverpur. But burials take place only in Fafamau and Shringverpur. Bodies are also cremated at Arail, which is a strip of land between two streams of the Ganga.

Who are these dead?

It is well known that those under the influence of Brahmanism cremate their dead. The Brahmins persuade them to do so. However, many Dalit and backward castes either consign their dead to the rivers or cremate them.

Avdhu Azad, a Dalit from the Azamgarh district, says, “Around 90 per cent of my community used to bury their dead at ghats in their villages. But now that they have access to vehicles, so they take the bodies to Varanasi or Vindhyachal, where they cremate or bury them on the banks of the Ganga. However, only the well-off Dalits cremate the dead.”

Ram Tej Harijan and Chhote Lal of Dabha Simar village in Faizabad district say that their community don’t cremate their dead. They say that for centuries they have been burying their dead. Till recently, the burials used to take place at Jamthara Ghat on the Saryu River in Ayodhya but now the Yogi government has moved the ghat a kilometre away. “Recently, Ramesh Kumar Maurya, around 40 years old, died of Covid-19. His body was cremated in keeping with the Covid protocol. But it is customary for the Maurya (Kushwaha) community people of the area to bury their dead.”

Pradeep Shukla of Fafamau Kodsar village in Prayagraj district says, “I have never seen lower-caste people cremating the dead. When a death takes place in their family, they don’t look for wood; they look for spades. They bury their dead or consign them to the river and from the very next day, start working to feed their families.”

Rituals cost thousands

At present, wood for cremations is quite costly. The prices are different at different ghats. For instance, wood is purchased from Sahson Chauraha for bodies being taken to Chhatnag Ghat, Daraganj Ghat and Jhonsi Ghat for cremation. It is sold for Rs 500-600 per quintal there. The price of wood at Daraganj and Fafamau Ghats is Rs 700-800 per quintal whereas at Shringverpur Ghat, it is Rs 1,200 per quintal. Besides, some money has to be paid to the Domraja (Dalit), who prepares the pyre and burns the body. But his charges are much lower than the charges of the Pandas (who belong to the lowest-ranking Brahmin subcaste) who conduct the last rites on Ganga ghats. They normally charge Rs 1,000-5,000 per body while Domrajas have to be paid between Rs 250 and Rs 1,000.

Prosperity and cremations

Ghabbu Patel, 40, of Pali village, Prayagraj died on the morning of 15 May 2021. Ghabbu, who used to work a handloom in Bhiwandi since he was 15, had become addicted to liquor and cannabis. He had moved back home after falling ill a few years ago. He was bedridden for the past two months. After his death, the community members suggested that his body be buried at Durvasa.Only cremation is allowed in the Chhatnag, Jhunsi and Rasoolabad ghats of the Ganga in Prayagraj. The option of burial is available only at Shringverpur and Fafamau.

But Ghabbu’s younger brother, who was friends with Brahmins, insisted that the body be cremated and not buried. That set off murmurs of protest among his community as the Kurmis do not cremate their dead but bury them. Ghabbu’s aunt, who had died two years ago, was also buried on the bank of the Ganga. Even among the savarnas, the unmarried and the minors are buried.

All Dalitbahujans had been burying their dead in Prayagraj, Pratapgarh, Jaunpur, Gorakhpur, Azamgarh, Kanpur and other districts. But with growing prosperity, they have begun to ape the savarnas. That is why some of them have started cremating their dead and performing elaborate rituals.

Cremation is Aryan culture

Cremation has been a part of the Aryan culture. Among the savarnas (especially the Brahmins and the Rajputs), a close male relative lights the pyre. This ritual is called “mukhagni dena” or “daag dena”. The person who gives “mukhagni” performs the “pindadan” of the dead. The cremation is followed by the ritual of tying a “ghat” (an earthen pot) to the peepal tree, tonsuring, pindadan on dashgaatra (offering of grains on the 10th day), ekodashah (11th day purification ritual) and tehranvi (13th day) feast. All these rituals are time-consuming and expensive. The toiler Dalitbahujan castes have neither the money nor the time to perform cremations and the subsequent brahmanical rituals. Even in the pandemic, they are sticking to their tradition of burying the dead.

The only new element today is that a large number of Dalitbahujans are dying of Covid-19 for want of treatment. They figure nowhere in the government records but the hundreds of bodies floating in the Ganga in Mahadev Ghat, Chausha, in Bihar’s Buxar district and in Ghazipur and Balia in Uttar Pradesh and the fresh graves on the banks of the river at Unnao and Prayagraj are testimony to this fact.

(Translation: Amrish Herdenia; copy-editing: Anil)

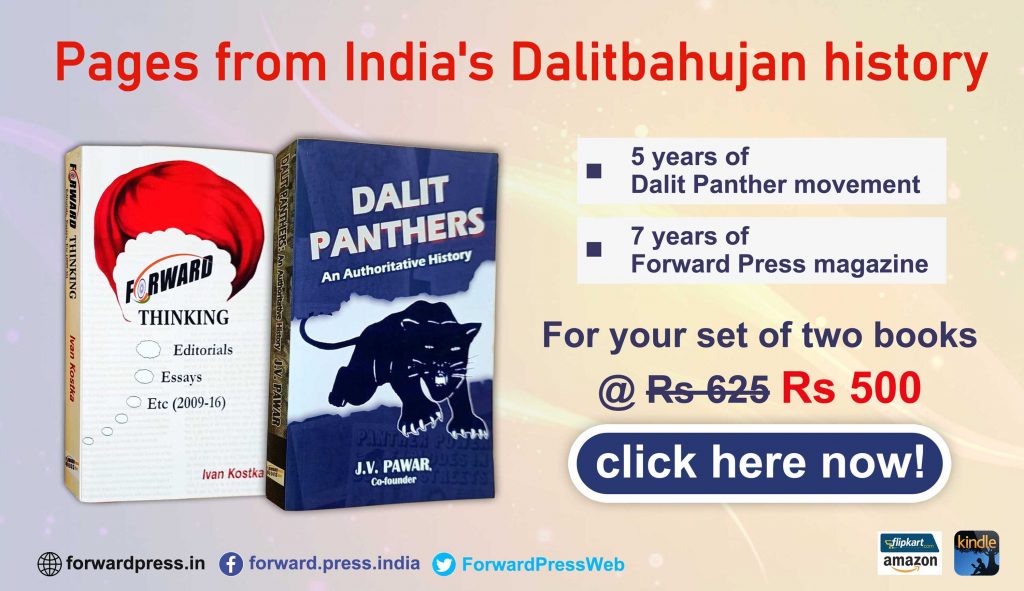

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History