Today, Scheduled Castes constitute a third of the population of the Indian state of Punjab – which is more than the proportion of SCs in any of the other states and union territories. Yet, their share in agricultural land of this predominantly agricultural state is the least. Less than five percent of them are small-time cultivators. Though they are enumerated along with other caste communities as part of an administrative division, such as a village, in the census records, they actually live in segregated Dalit settlements situated in the periphery of the villages. The segregated SC peripheries are contemptuously called Chamarlees in Doaba, Thathees in Malwa, and Vehras in Majha – the three distinct spatial-cultural regions of the state. Like all other integral segments of the syncretic Punjabi qaum, the Punjabi SCs are well known for their valour in the missions of the Khalsa armies of Guru Gobind Singh against regimes of injustice and social oppression. The desire for a life of dignity prompted them in the second half of 1920s, to organize themselves under the Ad Dharm movement, the maiden movement of the Untouchables in pre-Partition Punjab, launched 11-12 June 1926. The Ad Dharm movement ran parallel to but independent of various other contemporary Adi movements that emerged in the rest of India.

Babu Mangu Ram Mugowalia (14 January 1886 – 22 April 1980) was the founder of the Ad Dharm movement. He belonged to a family of leather workers from a village called Mugowal in Hoshiarpur district. His father wanted to educate him so that he could be of help in his leather business – for instance, in reading the orders drafted in English. Despite hailing from a relatively well-off family, Mangu Ram faced social exclusion for his so-called low birth at his school in a nearby village called Bajwara and was forced to quit studies abruptly without completing his matriculation. Thereafter, in search of a comfortable life, like the early emigrants from Doaba, Mangu Ram also arrived in the United States of America in 1909. He worked in the lumber industry and farms to make a living. That was the time when Punjabi emigrants in North America were planning to form a radical organization for the liberation of colonial India. Mangu Ram became an active member of the Ghadar Lehar (movement) founded in 1913. He was one of the five members of a Ghadrite group who were assigned the herculean task of ferrying weapons to India for an armed rebellion against the British rule. But SS Maverick, the ship that was bought to transport weapons was caught en route and Mangu Ram ended up in the Philippines, where he spent the following 12 years incognito. When he finally returned to his native village in 1925, it took everyone by surprise because rumours of his alleged hanging had got there ahead of him.

Babu Mangu Ram Mugowalia is to Punjab what Mahatma Jotirao Phule is to Maharashtra. Just as Maharashtra’s Shudratishudra movement was conceived and initiated by Phule, Punjab Untouchables’ movement was conceived and initiated by Mangu Ram. Phule considered Maharashtra’s Shudratishudras to be indigenes or aborigines. Similarly, Mangu Ram saw Punjab’s Untouchables as the indgenes or aborigines. If Phule was influenced by the writings of Thomas Paine (1737-1809), the English-born American political activist, theorist, philosopher and revolutionary, Mangu Ram learnt his lessons of equality and freedom from the proclaimed democratic and liberal values of the US where he came into contact, during his sojourn, with the revolutionary freedom fighters popularly known as Ghadari Babas of the historic Ghadar Lehar. This cemented his resolve to fight for a dignified life for the masses by liberating India from the clutches of the British Empire, and to establish in its place a democratic and egalitarian home rule that secured equality and freedom for all, irrespective of caste, class, creed, language, gender and regional differentiations.

On return to his native village, after spending 16 years abroad, Mangu Ram though was shocked to see that the practice of untouchability continued unhindered. In his own words: “While living abroad I had forgotten about the hierarchy of high and low, and untouchability, and under this delusion returned home in December 1925. The disease from which I had escaped started tormenting me again. I wrote about all this to my leader Lala Hardyal ji, saying that until and unless this disease is cured, Hindustan could not be liberated. Hence, in accordance with his orders, a programme was formulated in 1926 for the awakening and upliftment of the Achhut qaum [Untouchable community] of India” (Kaumi Udarian 1986: 23-24). Consequently, he decided to dedicate the rest of his life for the emancipation and empowerment of his fellow so-called low-caste people. He established an elementary school in his native village for the Untouchables, who later came to be designated Scheduled Castes under the Government of India (Scheduled Castes) order, 1936, which contained a list (or schedule) of castes throughout the British-administered provinces. Following in the footsteps of his revolutionary Ghadarite leadership in the US, he aspired to both fight against the caste-based social evil of untouchability and to replace it with an all-encompassing social freedom, and for India’s political freedom. Like Phule in Maharashtra, he faced stiff opposition from the so-called upper castes in his fierce struggle against oppressive structures of domination.

The Ad Dharm movement pioneered by Mangu Ram soon became a household name among the Untouchables of Punjab like the Satyashodak Samaj movement was in Maharashtra. Seth Kishan Das of Bootan Mandi – a well-known local leather merchant – helped build the headquarters of the movement, called “Ad Dharm Mandal”, in Jalandhar. Mangu Ram’s untiring efforts took the movement to the doorsteps of all the Untouchables in the region and he soon emerged as their cult figure. Under the flag of Ad Dharm movement, he fought for the long-denied land rights of the SCs who were legally debarred, along with other non-agricultural castes, from owning agricultural land under the Land Alienation Act of 1900. Moreover, under the local customary law, popularly known as “rayit-nammas”, the lower castes were also deprived of ownership rights to the plots on which their houses stood in the segregated neighbourhoods. They were not allowed to build pucca houses. They would build mud/thatched houses and in return were supposed to perform some begar (forced labour without wages) in the farms of the legal owners of their residential plots.

Another important campaign that the Ad Dharm movement undertook was for special legal provision of education and reservation in government employment for the Untouchables. It was for the first time that the Untouchables could come together to fight for a dignified life and to collectively press for their long-pending claim for a share in the local structures of power.

In the wake of the limited democratic political process prised from the British government in 1919 for the institutionalization of the electoral system, every community was busy in organizing its respective members into socio-political force (political party/social organization). As a young man who had returned from the US and the Philippines and who had been meticulously chiselled in the company of the Ghadarite Babas, Mangu Ram was able to bring together many of his fellow community members to build a separate social and political organization on a par with that of the upper-caste communities like the Hindu Mahasabha of the upper-caste Hindus, Muslim League of the Muslims and Singh Sabhas of the Sikhs. This limited election-based legislature-forming-process also led to the formation of similar Adi movements in other parts of the country, such as Adi-Andhra, Adi-Dravida and Adi-Karnataka in South India, and Adi-Hindu in Uttar Pradesh. Though these different Adi movements emerged almost at the same time in different regions of the country, there is no evidence to prove that one gave rise to another. Each Adi movement was influenced by the prevailing local situation.

In the poster announcing the first annual meeting of the Ad Dharm movement, Babu Mangu Ram Mugowalia, along with Swami Shudranand and Babu Thakur Chand, devoted the entire space to the hardships faced by the Mulnivasis at the hands of the caste Hindus. He also made an appeal to the Mulnivasis to come together to chalk out a programme for their liberation and upliftment. Addressing them as brothers, he said:

We are the real inhabitants of this country and our religion is Ad Dharm. Hindu Qaum came from outside to deprive us of our country and enslave us. At one time we reigned over ‘Hind’. We are the progeny of kings. Hindus came down from Iran to Hind and destroyed our Qaum. They deprived us of our property and rendered us nomadic. They razed our forts and houses, and destroyed our history. We are seven crores in number and are registered as Hindus in this country. Liberate the Adi race by separating these seven crores. … Our seven crore population enjoys no share at all. We reposed faith in Hindus and thus suffered a lot. Hindus turned out to be callous. Centuries ago, Hindus suppressed us – sever all ties with them. What justice can we expect from those who are the butchers of the Adi race. The time has come; be cautious, now the government listens to appeals. With the support of a sympathetic government, come together to save the race. Send members to the Councils so that our Qaum is strengthened again. British rule should remain forever. Pray to God. Except for this Government, no one is sympathetic towards us. We should never consider ourselves as Hindus; remember that our religion is Ad Dharm (Kaumi Udarian: 1986: 21-22).

Keen readers of Babu Mangu Ram Mugowalia have observed that he was conflicted on the issue of the British Raj. On the one hand, he feared even greater oppression under Hindu majoritarian rule than under the British – whom he also viewed as possible partners in facilitating a more equal Indian society – but on the other hand he aspired for the dignity of national independence, which necessitated the removal of the British. This remained a recurring paradox in his political approach till Indian Independence in 1947. In the meantime, he, along with other leaders of the Ad Dharm movement, chose to restore the lost dignity and freedom of the Untouchables by detaching them completely from Hinduism and reconsolidating them into their own ancient religion (Ad Dharm). The long domination by the Aryans, they alleged, made them oblivious of their native religion.

Thus, what made the Ad Dharm movement the most politically noticeable and popular of its time was the farsightedness of its visionary leaders in setting the goal of bringing diverse Untouchable communities under a single flag and to transform them into a distinct single community that was part of the Punjabi qaum. This was the most crucial political move on the part of Mangu Ram, the master strategist, who intervened at the vital moment when limited direct elections were scheduled to be held in the state. He pressed for a separate religion for the Untouchables of Punjab to be recorded in the 1931 Census, who in his opinion weren’t Hindus, Sikhs, Muhammadans or Christians. Mangu Ram would reiterate that the Untouchables were the original inhabitants – Mulnivasis (indigenes/aborigines) – of this nation. He would say that the alien Aryan invaders deprived them of their kingdom, looted them, and finally enslaved them. In his brilliant article entitled Achhut da Swaal (The Question of Untouchability), published in the Kirti monthly of the Kirti Kisan party in 1929, Shaheed Bhagat Singh, writing under the pseudonym of Vidrohi, supported the Ad Dharm leadership in its tirade against the caste system and for a separate religion, but at the same time also cautioned them to keep their distance from the British.

Mangu Ram would say that the Mulnivasis, the natives of this region, had forgotten their gurus and other religious symbols during their long period of persecution under the rule of the outsiders. They had been condemned as impure and declared unfit to have their own theology. In order to establish and legitimize their hegemony over the enslaved Mulnivasis, the Aryan invaders declared themselves the top three Varnas (Brahmans, Kshatriyas and Vaishyas) in the fourfold Chatur-Varnavyavastha. The natives of the conquered land were pushed into the fourth Varna of Shudras – consisting of the artisan castes – and still others were reduced into lowest of the low castes, contemptuously dubbed as Varna-less and untouchable.

The assertion by Mangu Ram that the Untouchables were the original inhabitants of this land had an enormous psychological impact on them. It instilled in them pride and self-esteem and provided a theological basis for their new identity. The Ad Dharm was based on the teachings of the saint-poets of the Bhakti movement, particularly Ravidas, Valmiki, Kabir and Namdev. In fact, the leaders of the Ad Dharm movement placed Guru Ravidas at the centre of their discourse around which the entire socio-political and spiritual paraphernalia of the movement and separate religion was woven. In this way, Mangu Ram played the dominant role in defining the markers of a distinct identity and restoring lost heroes, gurus, and rich cultural heritage to the natives. He imbued them with the yearning to become rulers themselves.

Mangu Ram’s efforts paid off when the British government caved in to the Ad Dharmis demand and granted Ad Dharm the status of a separate religion. During the Census of 1931, around half a million Scheduled Castes in Punjab declared themselves as followers of their newly recognized religion Ad Dharm, or Ad Dharmis. Another equally great achievement of the Ad Dharm movement was that it swept the reserved provincial assembly seats of Punjab in the 1937 and 1946 elections, which made it an important stakeholder in the legislature, perhaps for the first time in the history of the Untouchables in colonial India.

Moreover, the Ad Dharm movement proved to be the fertile ground for the sowing of seeds of the mission of Babasaheb Dr B.R. Ambedkar in Punjab. During Dr Ambedkar’s struggle for a separate electorate for the Depressed Classes at the London Round Table conferences, Mangu Ram supported him. He sent many telegrams supporting Ambedkar during his confrontation with Mahatma Gandhi over the question of the leadership of the Depressed Classes in India.

Eminent American social scientist Mark Juergensmeyer has documented in his classic Religious Rebels in the Punjab: The Ad Dharm Challenge to Caste, the incredible contribution made by Ad Dharm movement in generating social and political consciousness among the lowest of the low to help them rise against the centuries-old discriminatory caste system and to establish an egalitarian socio-political order modelled on Guru Ravidas’ Begampura.

Both Jotirao Phule and Babu Mangu Ram were moved by the plight of a large oppressed population in their respective regions, the Shudras and Atishudras in Maharashtra and the Untouchables in Punjab, which they themselves were part of, and mobilized them against the oppression. Both Phule and Mangu Ram traced the oppression to the invasion of their land by Aryans who had arrived from Central Asia and to the perpetuation of the subjugation of the natives (Mulnivasis) through the myths propagated in the form of scriptures written by the invaders. In the brilliantly articulated alternative sociopolitical narratives of Phule and Mangu Ram, we thus have the foundation for an alternative politics for an egalitarian social order across the various spatial-cultural regions of India. We have in them the foundation to build the Ambedkarian discourse of social democracy and eventually bring about the “annihilation of caste”.

References:

Juergensmeyer, Mark (2009). Religious Rebels in the Punjab: The Ad Dharm Challenge to Caste, New Delhi: Navayana.

Kaumi Udarian (Punjabi), Vol 1, No 2, January 1986, pp 21-24 (Jalandhar), C.L. Chumber, ed.

Copy-editing: Anil

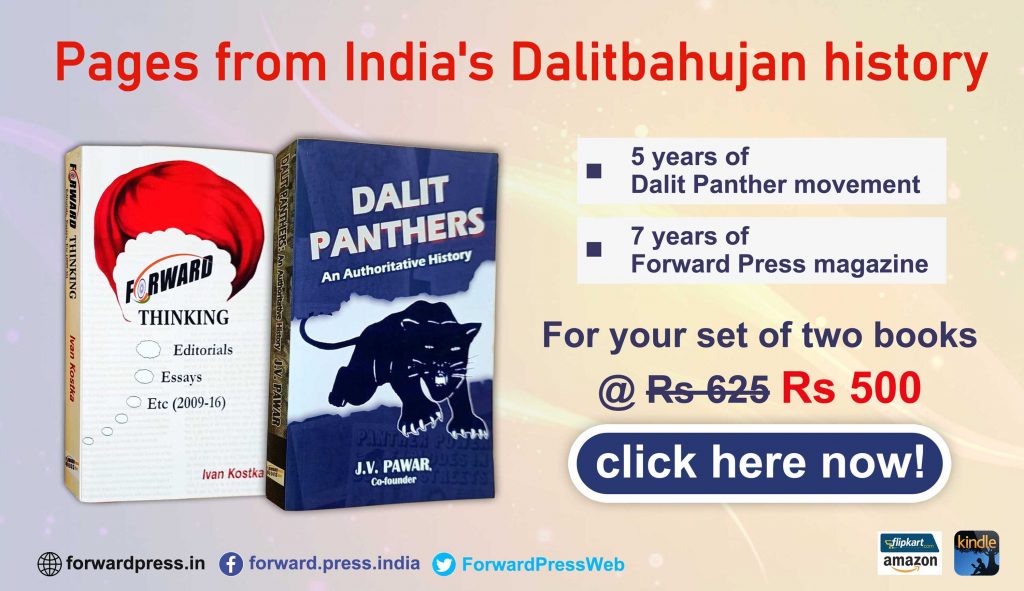

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History