Among all the states of India, Punjab has the largest proportion of population that falls under the Scheduled Caste (SC) category. Yet, the category is not homogenous. Far from it, the SCs here are made up of 39 castes scattered over varied religions and deras. These deep, hierarchical divisions offer insight into why the SCs have not made their presence felt in the elections.

The Scheduled Castes (SCs) constitute 31.94 per cent of the total population of the state, while SCs make up only 16.6 per cent of India’s population. In many of Punjab’s districts, the share of the SCs is a third or more, that is from 32.07 per cent to 42.51 per cent. The SC population in Punjab is predominantly rural, and 57 villages have a 100 per cent SC population while in another 4,799 villages (39.44 percent), the share of the SC population is 40 per cent or more. Given their high concentration, a 25 per cent reservation quota has been set aside for SCs in state services. In the Punjab Legislative Assembly, 34 of the 117 seats are reserved for the SCs. Of the 13 Lok Sabha constituencies in Punjab, four are reserved for SCs. However, the parties of the SCs – Labour Party of India (LPI), Scheduled Castes Federation (SCF), Republican Party of India (RPI) and Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) – were never able to do justice to the numbers.

The primary reason is that the 39 castes that make up the SC community are themselves scattered over several religions (Hinduism, Sikhism, Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, and the Ravidasia Dharm) as well as a large number of deras/sects. Another possible reason could be the weak brahmanical influence in Punjab due to the visible and intangible transformative role played by the Islam and Sikhism, which – unlike in the Hindi belt – did not necessitate a political party for all of SCs. Furthermore, allurement of prominent positions often given to influential SC leaders in the mainstream political parties has, by design or otherwise, preempted electoral success of SC-based political parties. Charanjit Singh Channi, the 17th chief minister of Punjab, is the latest case in point. His elevation has dramatically propelled the issue of caste-based political identity of lower castes to the centre stage of contemporary Punjab politics. Channi hails from the Ramdasia Sikh SC community and is a Congress party Member of Legislative Assembly (MLA) from Chamkaur Sahib, a constituency reserved for SCs.

As noted above, the SCs of Punjab are not a homogeneous category. The various SCs observe graded caste hierarchy as in the Varna system – although all SCs have been treated as outcaste and Untouchable by those who belong in the Varna system in accordance with the brahmanical texts. They are endogamous, have distinct social identities and varied economic conditions. Almost everyone locates herself/himself above someone else. All this has not only made the process of consolidation among them a herculean task but also pushed them further into the whirlpool of various protracted social conflicts. Not much scholarly work has been undertaken to explore how caste-based cleavages among the former Untouchables has led to their political fragmentation.

Many castes among outcastes

Among the SCs, Ramdasias, Mazhabis, Rai Sikhs, and Sansis follow the Sikh religion. Balmikis consider themselves Hindus. Ravidasias and Ad Dharmis have recently founded a separate religion – Ravidasia Dharm – though there is an ongoing internal contestation, with one section arguing for a separate religious identity while the other strongly in favour of keeping intact centuries-old affiliations with the Sikh religion represented by the Guru Granth Sahib, which also carries the verses of Guru Ravidas (Raidas). Even though a section of Ad Dharmi and Ravidasias have established their separate religion, many of them still practise Sikh rituals and follow the social-spiritual philosophy of various deras/sects along with keeping their Ravidasia identity. They are therefore bi-denominational in practice, and are mostly concentrated in the Doaba region of Punjab, with only a very low percentage in the Majha region. Mazhabis are mainly settled in Majha and Malwa regions. Ramdasias and Rai Sikhs are largely concentrated in Malwa, and Balmikis in both the Doaba and Malwa regions.

In terms of political affiliations, Chamars and Balmikis are generally considered to be closer to the Congress whereas Mazhabis, Ramdasias, Rai Sikhs and Sansis to the Akali Dal. However, political affiliations remain ephemeral, shifting in accordance with the grammar of electoral politics. Out of the 39 SCs, four major castes of Chamar (23.45 per cent), Ad-Dharmi (11.48 per cent), Balmiki (9.78 per cent) and Mazhabi (29.72 per cent) constitute 74.44 per cent of the total SC population in Punjab. These four major castes fall under the two broader Balmiki/Mazhabi and Chamar[1] caste categories. However, before the inclusion of the Rai Sikh community in the SC category, the two major SC caste clusters enjoyed 83.9 percent share of the total SC population. The 2001 Census revealed that the Balmiki/Mazhabi Caste Cluster made up 42.8 percent and Chamar Caste Cluster 41.1 percent of the total SC population. Among these two distinct clusters, Mazhabis are the largest in number followed by the Chamars, Ad Dharmis and Balmikis. The rest of the 35 castes constitute less than a third (25.56 per cent) of the state’s total SC population. They are equally heterogeneous and have been divided into two clusters of 18 castes of Vimkut Jatis and Depressed Castes and of 18 Peripheral/Invisible Castes. Vimukt Jatis, or Denotified Tribes, are those communities that were declared Criminal Tribes by the British administration under its notorious Criminal Tribes Act 1871. The Depressed Castes consist of smaller and the most marginalized among the SCs in the state, and have been grouped together by the Punjab government for targeted special assistance under various development schemes.

The Balmiki/Mazhabi Caste Cluster (39.5 percent) clubs together Balmikis and Mazhabis, which are two of the major castes. Over the last few years, Valmiki-Ambedkarite identity has been taking root within many sections of the Balmiki community. Valmiki with a pen in his hand, along with the inspiring slogan “educate, agitate, organize” embossed over the picture of Dr Ambedkar, represents this Valmiki-Ambedkarite identity forged with the aim of disseminating education and critical consciousness among Valmikis – one of the least educated SC castes in Punjab[2]. This spurred efforts to persuade them to realize not only the potential of the agency of education for their upward social mobility, but also the futility of nurturing antagonism with their rival Chamar Caste Cluster.

Those from the Balmiki/Mazhabi Caste Cluster who embraced Sikhism are called Mazhabis and consider Baba Jiwan Singh as their Guru. They are mostly concentrated in Majha and Malwa regions – Ferozepur, Gurdaspur, Amritsar, Faridkot, Mansa and Bathinda districts – where they are engaged in a fierce struggle over their claim on the Panchayats’ common agricultural lands for self-cultivation. They outnumber other SCs in Faridkot and Ferozepur districts. Despite this impressive numerical strength, they remain the most deprived section among the SCs and have the lowest literacy rate (42.3 per cent). A majority of them (52.2 per cent) are still languishing in low-wage agricultural farm jobs. Though the “Siris” (labourers attached to a landlord by virtue of an advance paid to them and in some cases interest accruing on the advance and other loans) system is largely a thing of the past, isolated cases still exist in the Malwa region. However, over the years their position has improved, particularly after the implementation since 1975 of the contentious policy of reservation sub-quotas in Punjab.

Chamar Caste Cluster

The Chamar Caste Cluster (34.93 per cent) consists of two castes, Chamars and Ad-Dharmis. Chamar is an umbrella caste category. It includes Chamar, Jatia Chamar, Rehgar, Raigar, Ramdasia and Ravidasia. Though this cluster is largely confined to the Doaba region of the Punjab, Chamars have a substantial presence in Gurdaspur, Rupnagar, Ludhiana, Patiala and Sangrur districts. Traditionally, Chamars have been condemned as polluted and impure by the “touchable” castes because of their occupational contact with animal carcasses and hides, but they consider themselves Chandravanshi by clan and claim highest social status among SCs. In the mid-1920s, some of them established a prosperous leather-business town (Boota Mandi) on the outskirts of Jalandhar city. They were also the main force behind the emergence of the famous Ad Dharm movement in Punjab in the mid-1920s. In the Census of 1931, many of them registered themselves under the then newly declared religion of Ad Dharm and came to be known as Ad Dharmis. However, after India’s independence, Ad Dharm was redefined as one of the SCs – the Ad Dharmi caste.

Ravidasias and Ramdasias, though included within the larger Chamar caste category, consider themselves socially higher than the others in the category. The distinction here is traced to their diverse occupations. The leather-working sections of the Chamar caste are called Ravidasias and the weavers who converted to Sikhism came to be known as Ramdasias. Those weavers who did not convert to Sikhism are called Julahas. The Julahas are also called Kabirpanthis and listed as a separate caste among SCs. Ramdasias converted to Sikhism during the time of Guru Ram Das, the fourth guru of the Sikh faith, and have since then been called Ramdasias[3]. A majority of them are Sahajdhari Sikhs (those who believe in the Sri Guru Granth Sahib but do not maintain the external symbols of the faith). Babu Kanshi Ram, though clean shaven, was a Ramdasia Sikh. They are also known as Khalsa biradar. Though Ramdasias are Sikhs, they are nonetheless included within the larger “Hindu” caste category of Chamar on the list of SCs.

Ravidasias (leather workers) and Ramdasias (weavers) strictly practise endogamy. They are often confused with Sikhs, since many of them keep the beard and unshorn hair akin to baptised Sikhs, and also believe in the Guru Granth Sahib (the Sikh sacred scripture), though many of them do not identify as Sikhs. Though there are unquestionably strong interlinkages between the Sikh religion and the Ravidasia sect, the latter declared itself a separate religion, Ravidasia Dharm, on 30 January 2010.

Vimukt Jatis and Depressed Castes Cluster

The Vimkut Jatis and Depressed Castes Cluster includes 13 Depressed Castes (hereafter DC) and eight Denotified Tribes/Vimkut Jatis. DCs comprise Bazigar (2.72 per cent of the total SC population), Dumnas/Mahasha/Doom (2.29 per cent), Megh (1.59 per cent), Bauria/Bawaria (1.41 per cent), Sansi/Bhedkut/Manesh (1.38 per cent), Pasi (0.44 per cent), Od (0.36 per cent), Kori, Koli (0.28 per cent), Sarera (0.16 per cent), Khatik (0.16 per cent), Sikligar (0.13 per cent), Barar/Burar/Berar/Barad (0.10 per cent), Bangali/Bangala (0.05 per cent) and Bhanjra (0.04 percent). Out of these 13 Vimukt Jatis four – Bangala, Bauria, Bazigar Bhanjra, and Sansi (1.38 percent) – have also been identified as Denotified Tribes/Vimukt Jatis. However, within the DC category, Bazigar and Bhanjra are listed as separate castes. The eight Denotified Tribes/Vimkut Jatis are Bangala (0.05 percent), Barad (0.10 percent), Bauria (1.41 percent), Bazigar Bhanjra (2.76 percent), Gandhila/Gandil Gondola (0.04 percent), Nat (0.04 percent) and Sansi (1.38 per cent) and Rai Sikh (5.83 per cent). Rai Sikhs were recently added to the above caste cluster. They were one of the communities declared a Criminal Tribe by the British under the Criminal Tribes Act 1871. Rai Sikhs, the erstwhile Mahatam, are the fifth largest SC community (5.83 percent Census of India 2011) in Punjab, that is after the four major castes of Chamar, Ad Dharmi, Balmiki and Mazhabi. In terms of social hierarchy, the “touchable” castes considered them as almost on a par with (formerly) untouchable castes, and even though they were denotified in 1952, the stigma of criminal tribe designation continues to be an impediment to their progress even after almost seven decades of India’s independence. They are strictly endogamous, practise clan exogamy, and are mainly concentrated in the Ferozepur, Kapurthala, Jalandhar and Ludhiana districts, and have a substantial presence in 35 Assembly and seven Lok Sabha constituencies. Rai Sikhs have been pressing for reserved seats in the Punjab Legislative Assembly and in Parliament.

Peripheral/invisible Castes Cluster

This caste cluster comprises 18 SCs (Batwal/Barwala, Chanal, Dagi, Darain, Deha/Dhaya/Dhea, Dhanak, Dhogri/Dhangri/Siggi, Gagra, Kabirpanthi/Julaha, Marija/Marecha, Perna, Pherera, Sanhai, Sanhal, Sansoi, Sapela, Sikriband and Mochi), which together represent 10 percent of the total SC population. The numerical strength of some, for instance, the Chanal, Perna and Pherera castes, is less than 100 people. Other than the Dhanak caste (1.01 percent), each of the other castes in this cluster form less than 1 per cent of the SC population. Many have moved to cities and work in the informal private sector as manual labourers. Given their miniscule strength, and their traditional, hereditary occupations having been rendered irrelevant, these castes have not only become invisible, but also don’t figure in the popular caste discourse in the state.

Caste cleavages: SCs vs SCs

An important dimension of these schisms among the SCs is the meshing of religion and politics, and the divisive politics of SC reservation policy. The Balmiki/Mazhabi and Chamar caste clusters are sharply divided in terms of their affiliation to different sects and benefits they draw from the Punjab’s SC reservation policy . Factors such as their divergent cultural and religious outlooks, as well as highly differentiated educational and economic backgrounds, have conspired to pit them against each other.

Ad Dharmis and Chamars are ahead of all the other SCs. They have not only been the main beneficiary of the state reservation policies in education, government jobs and legislature, but some of them have also established a firm grip on the leather business, surgical industry and sports goods industry. Many have migrated to Europe, North America, and the Middle Eastern countries, which has further contributed tremendously towards their upward social mobility. They have not only excelled in business and multiple skilled-labour professions, but also established their separate caste identity through a strong networking of social organizations, religious bodies, international Dalit conferences, Ravidas Sabhas and deras/gurdwaras. They take pride in publicly flaunting their distinct social identity markers and take a keen interest in promoting their community and cultural heritage.

The Balmiki/Mazhabi Caste Cluster is even more numerous. However in comparison to the Chamar Caste Cluster, it is backward in terms of education, and the number of those with government jobs and those who have emigrated to the West. It blames the Chamar Caste Cluster’s cornering a chunk of the reservation quotas for its obvious backwardness and neglect. Though this cluster has a sharp internal division between Balmiki (Hindu) and Mazhabi (Sikh) castes, it has been able to forge a common front against the Chamar Caste Cluster and secure a special reservation sub-quota.

The 25 per cent SC reservation quota in Punjab government services was divided into two sub-quotas of 12.5 percent each in 1975 by the issuance of the Government of Punjab Circular No. 1818SW75/10451 during the chief ministership of Giani Zail Singh. One sub-quota was assigned to just the Balmiki and Mazhabis castes and the remaining 37 SC castes shared the other sub-quota. Years later, on 5 October 2006, this subcategorization of reservation became law: The Punjab Scheduled Castes and Backward Classes (Reservation in Services) Act, 2006. The Act made provisions similar to those in the circular. Section 4(5) of the Act states: “Fifty per cent of the vacancies of the quota reserved for Scheduled Castes in direct recruitment, shall be offered to Balmikis and Mazhbi Sikhs, if available, as a first preference from amongst the Scheduled Castes.” The creation of these reservation sub-quotas further reinforced the religious, social and cultural divide between the Balmiki/Mazhabi and Chamar caste clusters, as well as fostering unity between the Balmiki (Hindu) and Mazhabi (Sikh) SC castes.

Both these clusters have their distinct sects, gurus, pilgrimage centres, shrines, iconography and sacred scriptures. If Dera Sachkhand Ballan at Jalandhar and Sri Guru Ravidas Janam Asthan Temple at Seer Goverdhanpur in Varanasi have become the most sought-after pilgrimage centres for the Chamars and Ad-Dharmis, the Valmiki Tirath Dham at Amritsar carries the same spiritual value for the Balmikis and Mazhabis. What sacred scripture Amritbani Sri Guru Ravidas Ji Maharaj is to Ravidasias, Yog Vashisht is to Balmikis. If Guru Ravidas is the Shiromani (patron) Sant (preceptor) of Ravidasias, Maharishi Valmiki is the Adi-Guru for the Balmikis and Baba Jiwan Singh for the Mazhabis. The shrines of Ravidasias are called “deras”, whereas Balmikis called their religious places Anant (Adi Dharm Temple). While Ravidasias greet each other with “Jai Santan Di” and conclude their religious ceremonies with the line “Jo Bole So Nirbhay, Sri Guru Ravidas Maharaj Ki Jai”, the Balmikis say “Jai Valmiki and Jo Bole So Nirbhay, Srishtikarta Valmiki Dayavaan Ki Jai”.

Mainstream political parties often cynically exploit the above-mentioned social cleavages between the Chamar and Balmiki/Mazhabi caste clusters. Both the Indian National Congress (INC) and the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) supported the Balmikis and Mazhabis’ demand for a SC reservation sub-quota in the face of Chamars and Ad-Dharmis’ opposition. A petition against the 2006 sub-quota law is still pending in the Supreme Court.

The political support extended to a particular cluster often sharpens the inter-cluster division among the SCs with serious implications for an overall Dalit solidarity for the larger community’s interests. The Chamars and Ad-Dharmis didn’t have the support of the Balmikis and Mazhabis during the struggle of the historic Ad Dharm movement and the latter was indifferent to the skirmishes in Talhan, Meham and Vienna (Austria): These are a few instances of the friction between Balmiki/Mazhabi and Chamar caste clusters. A heated verbal duel between the Balmiki-Mazhabi and Ad-Dharmi-Chamar factions of the Congress party during its Chandigarh conclave over the allotment of a Rajya Sabha (Upper House) seat to Shamsher Singh Dullo (an Ad Dharmi) while overlooking Hans Raj Hans (a Balmiki) is an example of the contestations among the SCs. The Denotified Tribes who vehemently demand Scheduled Tribe (ST) status and contest their inclusion among SCs also often threaten Dalit solidarity. These groups proudly consider themselves the descendants of Rajputs who strategically became nomadic to further their fight against Mughal, and later, British rulers.

[1] The Balmiki/Mazhabi castes are derogatorily referred to as ‘Chuhra’ or ‘Bhangi’. The term ‘Chamar’ often has a derogatory connotation. Caste names (as in Census records) are used in the article for academic analysis. Any offence caused by such an exercise is deeply regretted.

[2] Based on author’s conversation with Darshan Ratan Ravan, the protagonist of ‘Valmiki-Ambedkarite identity’ and founder of the Adi Dharam Samaj, a socio-cultural and religious organization of the Valmiki community in Punjab, during an academic event at R.S.D. College (Ferozepur), 17 March 2015

[3] Based on author’s conversations with a large number of the members of the Ramdasia community

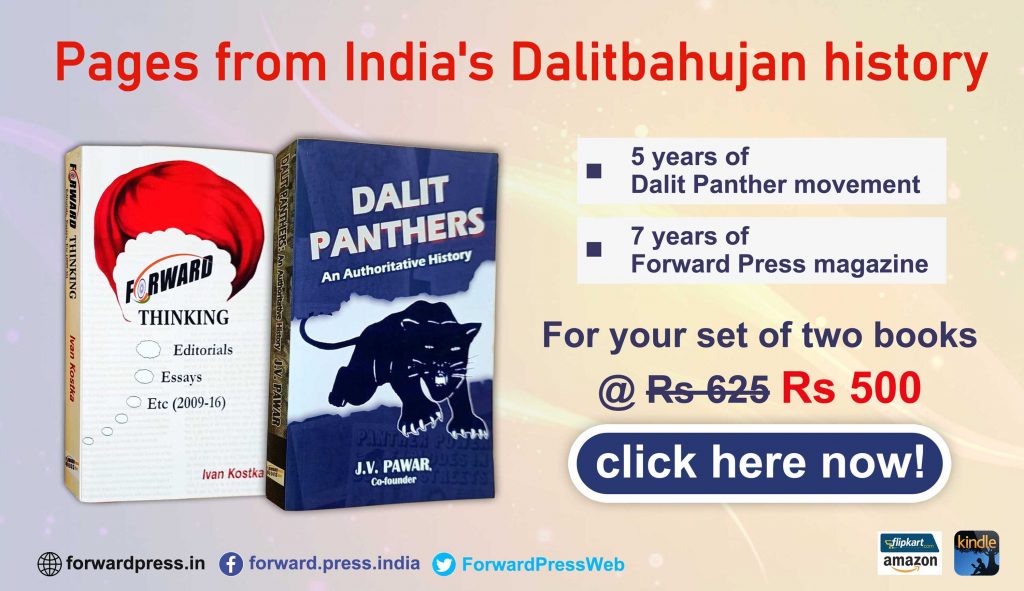

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History