The question of caste and the discrimination it entails has always been an electoral challenge for the Sangh Parivar and its political outfit, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Since its formation in 1980 and even in its earlier avatar as Bharatiya Jana Sangh, it has been the upper castes which have constituted the core base of the party. Both the Jana Sangh and the BJP had avoided the caste question, considering it as the biggest hurdle in their attempt to present a unified Hindu political majority. However, the implementation of the Mandal Commission report by the Vishwanath Pratap Singh-led National Front government in 1990 forced the BJP to engage with the caste question, especially the growing demands for political representation coming from OBCs, hitherto considered irrelevant in north Indian politics despite constituting the largest chunk of the population.

To counter the Mandal movement, the BJP responded by launching the Ram Janmabhoomi movement aimed at building the Ram temple in Ayodhya by replacing a medieval mosque. The Ram Janmabhoomi movement did find strong resonance among all sections of Hindus. However, the demolition of Babri Masjid on 6 December 1992 also resulted in the movement losing its political traction. It was not possible to galvanize popular support of the same magnitude for the construction of the Ram temple as for the demolition of the mosque which was presented by the Hindutva leaders as the symbol of centuries of Muslim domination over Hindus.

This decline of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement made the BJP realize that they could no longer keep themselves aloof from the growing mandalization of Indian politics, although when the Babri Masjid was demolished, the BJP government of Uttar Pradesh was headed by Kalyan Singh, an OBC.

In Bihar, it opted for indirect mandalization by forging alliance with the Samta Party, later renamed as Janta Dal (United). However, in Uttar Pradesh, under the social engineering formula of the then party’s general secretary (organization), K.N. Govindacharya, the BJP opted for direct mandalization by projecting backward caste leaders like Kalyan Singh, Vinay Katiyar and Uma Bharti as the faces of the party. These leaders became the local faces of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement. Ironically, all these backward-caste (OBC) leaders, despite establishing BJP as an important political force in Uttar Pradesh, never acquired the stature that was enjoyed by other upper-caste leaders like Kalraj Mishra, Lalji Tandon or Rajnath Singh in the state politics. In fact, Kalyan Singh was not only replaced as Uttar Pradesh chief minister in 1999 but was even suspended from the primary membership of the party. Though he returned to the party in 2004, he again resigned in 2009 before finally merging his Jan Kranti Party with BJP in 2014. By then, his stature in the party had diminished and was given the politically insignificant role of a governor.

Notably, after the demolition of the Babri Masjid, Kalyan Singh had started to present himself as the leader of the backward castes in the BJP and this was the prime reason behind his marginalization in the party. Somewhat similar fate awaited the firebrand leader Uma Bharti, who was also forced to resign from the post of Madhya Pradesh chief minister in 2004 and later expelled from the party. Like Kalyan Singh, she also returned to BJP but was never allowed to grow in stature and now has been forced to live a life in political oblivion.

Arguably, one of the major reasons behind the poor electoral performance of the BJP in Uttar Pradesh in both Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha elections from 2002 to 2014 was the absence of any popular backward caste leader in the party who could mobilize the backward castes in their favour.

What has changed since 2014

The rise of Narendra Modi and his trusted lieutenant Amit Shah as the all-important and supreme leaders of the BJP also resulted in the BJP opting for micro-level caste analysis in Uttar Pradesh. One of the prime reasons behind its spectacular performance in 2014 and 2019 Lok Sabha elections and 2017 Vidhan Sabha election is the support it acquired from the non-Yadav OBC caste groups who together constitute around 32 to 35 percent of Uttar Pradesh’s population. However, despite their unfaltering support, these backward castes have not got their due share in the BJP. In Uttar Pradesh, the rise of the BJP has in fact resulted in the rise of upper-caste MLAs. Among the BJP’s incumbent MLAs, 48.3 per cent are from the upper caste. Also, Keshav Prasad Maurya, an OBC leader who was the party’s state president in 2017 and played a crucial role in bringing non-Yadav caste groups closer to the party, was denied chief ministership, which was given to Yogi Adityanath, whose Rajput caste identity and growing Thakurwad (dominance of his own caste group) is widely talked about in Uttar Pradesh politics.

An example of BJP’s negligence with respect to the backward castes is its tacit refusal to conduct a caste-based census. However, voices of protest within the party’s OBC leadership demanding a caste based census are loud and clear. Notably, Sanghmitra Maurya, BJP’s Lok Sabha MP from Badaun and daughter of Swami Prasad Maurya (who recently quit BJP to join Samajwadi Party), has gone against the official party line to speak in favour of a caste-based census.

Similarly, despite repeated promises, the BJP government has not made any significant progress on implementing the Samajik Nyay Samiti (Social Justice Committee) report. One of the crucial reasons behind the BJP government not going ahead with any of the programmes capable of providing substantial benefits to the lower backwards like Nishads, Rajbhar, Maurya, Shakya, Saini, Pal and Prajapati has been the ideology of its parent organization, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), which underscores maintenance of an upper-caste hegemony in all spheres of life.

The RSS leadership looks at policies like a caste-based census or reservation as potential threats capable of disrupting its goal of creating a unified political majority. The compulsions of electoral politics have forced the BJP to go for a certain degree of pragmatism in dealing with OBC and the Dalit caste groups, by providing them representation in the legislative party and in party organization or making alliances with caste-based parties like Apna Dal (Sonelal) of Anupriya Patel and Nishad Party of Sanjay Nishad. Yet, none of these lower backward leaders enjoy any significant autonomy in the BJP. Its OBC and Dalit representatives have to operate within the upper-caste dominated and sustained framework. The upper-caste, brahmanical ideology of the RSS certainly is a limitation on the BJP when it comes to providing substantial benefits to the Backwards and Dalits.

Gauging these fault lines in the BJP’s politics, Samajwadi Party chief Akhilesh Yadav is diligently trying to make this election a contest between the OBC-Dalits and the upper-caste domination in the BJP regime. One of the catchy slogans of Samajwadi Party in this election is ‘Samajik Naya ka Inquilab Hoga, 22 Mein Badlav Hoga’ (There will be revolution of social Justice; there will be change in 2022). He has also made alliances with caste-based parties like Rashtriya Lok Dal led by Jayant Chaudhary, which has considerable influence over the Jat community in western Uttar Pradesh, and Om Prakash Rajbhar’s Suheldev Bhartiya Samaj Party. The Rajbhar caste group constitutes approximately 4 percent of UP’s population and is quite influential in almost two dozen seats of eastern UP.

However, the upcoming Uttar Pradesh election would have been interesting if the Samajwadi Party (SP) and Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) had contested it together. The BSP, led by Mayawati, despite not performing well since coming to power on its own in 2007, is still a major force in UP politics. In the 2017 assembly election, its vote share was around 22 percent, marginally more than SP’s.

In my view, the SP and the BSP made the mistake of breaking the alliance after the 2019 Lok Sabha elections failure. There were two simple reasons for the alliance failing in 2019. Firstly, it was a decision made too close to the elections and hence, the cadres and local leaders of both parties had very less time to interact and gel as a team. Also, both the parties got very little time to address detractors. Secondly and more importantly, this alliance had very little to offer at a national scale against Narendra Modi who is still India’s most popular leader nationally.

Since 2014, voters in India have voted differently in state and national elections. The BJP, though unchallenged nationally, is facing tough competition in state elections. Its failure in 2015 Bihar Assembly Elections and since then in Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh and recently concluded West Bengal Assembly Elections show that the BJP is not invincible in state elections. By fighting it together the SP and the BSP could really have made life difficult for the BJP in Uttar Pradesh, where despite their resorting to communal polarization, issues like unemployment, devastating mismanagement of the second wave of the Covid pandemic and inflation are finding resonance among voters. Going alone, would Akhilesh Yadav find it a tall order?

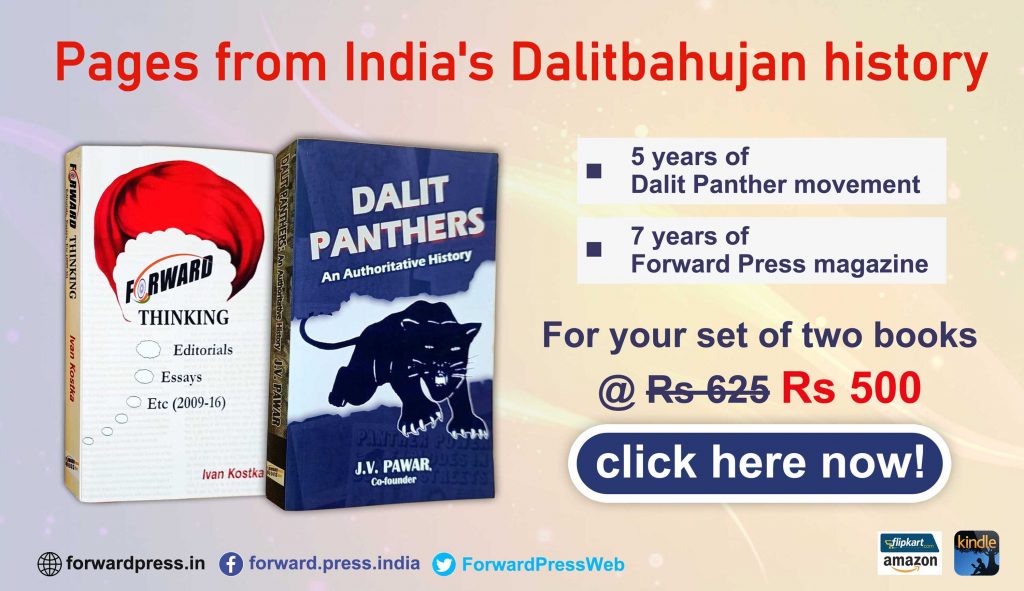

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History