The elections to the 403 assembly seats of Uttar Pradesh are underway in phases. As earlier, caste will play an important role in these elections, too. Everybody talks about castes as a thing of the past but the reality is that caste is the cornerstone of life in India. In fact, ever since we’ve had adult franchise, caste has dominated electoral politics and mobilization. In the 1960s, the Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP) had recognized caste as the deciding factor in politics while distributing tickets. SSP leader Ram Manohar Lohia had mobilized people particularly, the Other Backward Castes (OBCs), on two planks. One was integration and homogenization of sub-castes and another was reservation in educational institutions and services. The slogan at the time went, “Samsopa [SSP] ne badhi gath pichde pave sau mein sath” (SSP has taken a vow that it won’t rest until the Backwards get 60 out of 100.) The role of caste in elections was brought to the fore by late Prof Rajni Kothari, the noted political scientist. Caste is so alive in every nook and cranny of the country that even the communists for whom caste is anathema could not stay away from it. For instance, in the 2018 Telangana Assembly elections, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) [CPI(M)] banked more on caste factors than on class issues [R. Vaidhyanathan (2019), ‘Caste as Social Capital’, Westland, p 111].

The case for a larger Gurjar representation in Uttar Pradesh

Some Gurjars have remained Tribals (animists), while others have embraced Hinduism, Islam or Sikhism over the centuries and are spread across different states (Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Kashmir and Punjab (In the Amethi assembly constituency of Uttar Pradesh, the Muslim Gurjar community is said to constitute around 60 thousand voters). It has been classified variously as OBC, Denotified Tribe (DNT) and Scheduled Tribe (ST) in the different states. In the 403 assembly constituencies of Uttar Pradesh, Gurjars have a presence in as many as 77, which is 19 per cent but presently, there are five Gurjar legislators, which is 1 per cent. We could categorize the 77 constituencies into six categories in terms of the size of the Gurjar population (see table).

Gurjar voters in 77 Assembly Constituencies of Uttar Pradesh

| Range of Voters | No of Constituencies | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 0-10,000 | 16 ( 20.78%) |

| 2. | 10,000-20,000 | 23 (29.87%) |

| 3. | 20,000- 30,000 | 10 (13.00%) |

| 4 | 30,000-40,000 | 06 ( 07.79%) |

| 5 | 40,000-50,000 | 7 (09.09%) |

| 6. | 50,000 and Above | 15 (19.48%) |

Source: Data obtained from political and social workers

As shown in the table, 38 constituencies fall under the 20,000 and above range. What this means is that the Gurjar community in Uttar Pradesh can potentially seek the election of 38 MLAs from among them. In the constituencies of 10,000-20,000 range, the Gurjars could play an important role in the election of MLAs or even be themselves elected if they organize and find common ground with other farming castes like Jat, Yadav and Ahir.

Caste affiliation in regional political parties

Most of the regional parties are heavily based on a caste voter base, like the Janata Dal (Secular) in Karnataka (Vokkaliga), the AIADMK ( Thevar), the PMK (Vanniar) and DMK (OBCs and Muslims) in Tamil Nadu; the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) (Kamma) in Andhra Pradesh; the Shiv Sena (Maratha) in Maharashtra; the Samajwadi Party (Yadav and Muslim); the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) (Jatav); and the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD) (Jat) in Uttar Pradesh. Smaller parties like Apna Dal (Kurmi) and Azad Samaj Party (Jatav) also bring votes of specific castes to the alliances they are part of. The caste that a party is most dependent on can be likened to the locomotive of a train and the rest of the castes to its coaches.

How to get a bigger share of UP assembly

The Gurjar community needs to learn from the model adopted by other regional parties. However, while adopting the model, its social and political leaders should ensure conformity of intrinsic and extrinsic social norms during mobilization. It is said that a hundred Gurjars have one mother but it does not seem to be the case on the political front. Hence, mobilization needs to be done meticulously because we have seen an effort fail in 1996 in the western region of Uttar Pradesh and the National Capital Region (NCR). This particular attempt at mobilization resulted in two factions: Bharatiya Vikas Party and Dehat Morcha. Expectedly, the factions failed to make a mark in the elections.

There is a need to build social capital across the state through the creation of organizations and networks in a way that would provide an enabling environment for various stakeholders to participate in decision-making from micro to macro levels. It would promote collective action among members of the community. Building trust should be a priority so that proper coordination and cooperation between and among different organizations can take place. In order to build social capital, there is a need to activate dormant institutions (micro, meso and macro levels), associations, community-based organizations and grassroots movements.

To conclude, the representation of Gurjars in the Uttar Pradesh Assembly can increase and be commensurate with its presence in the different constituencies only if there is a concerted effort towards building the social capital of the community.

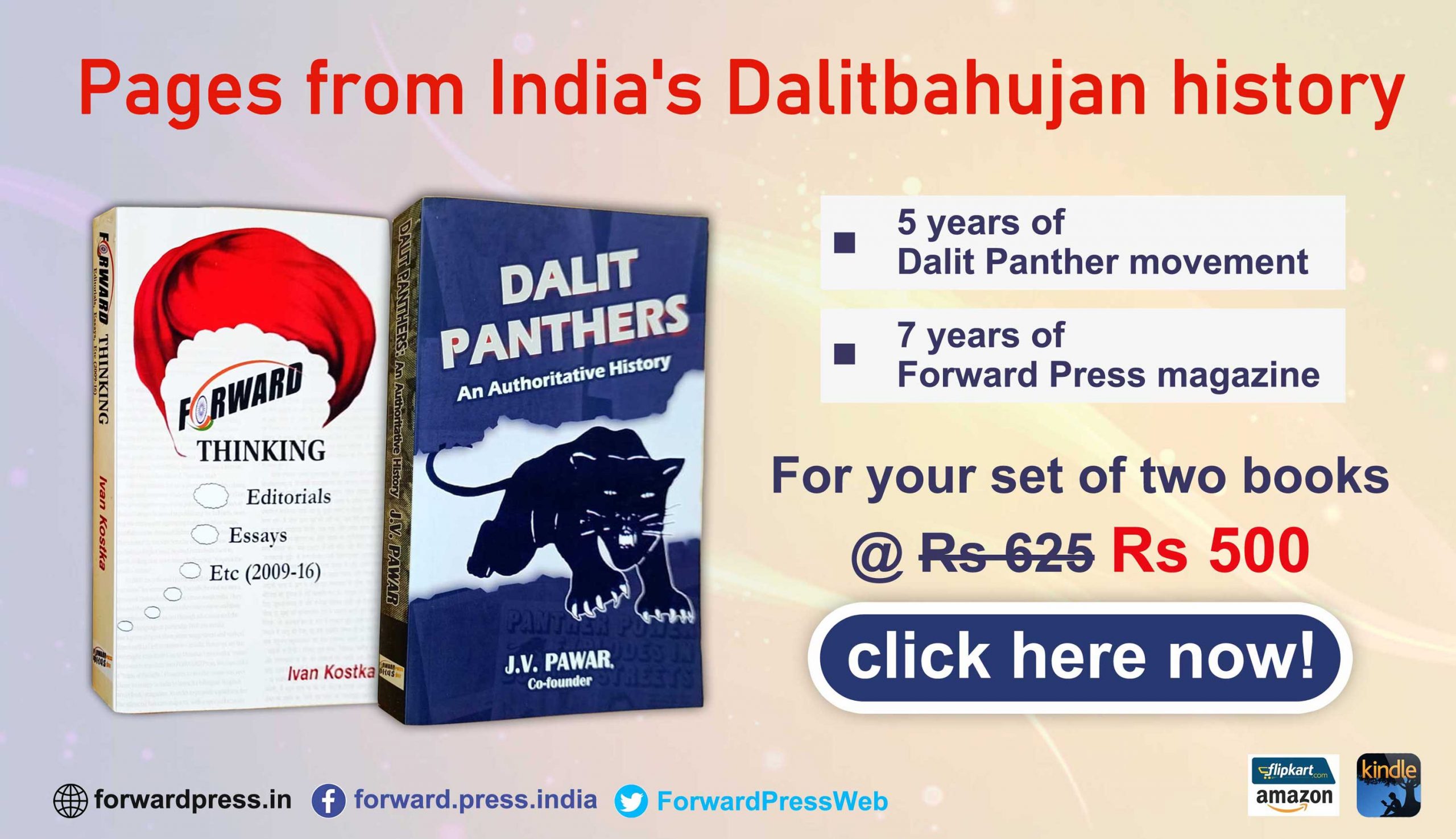

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History