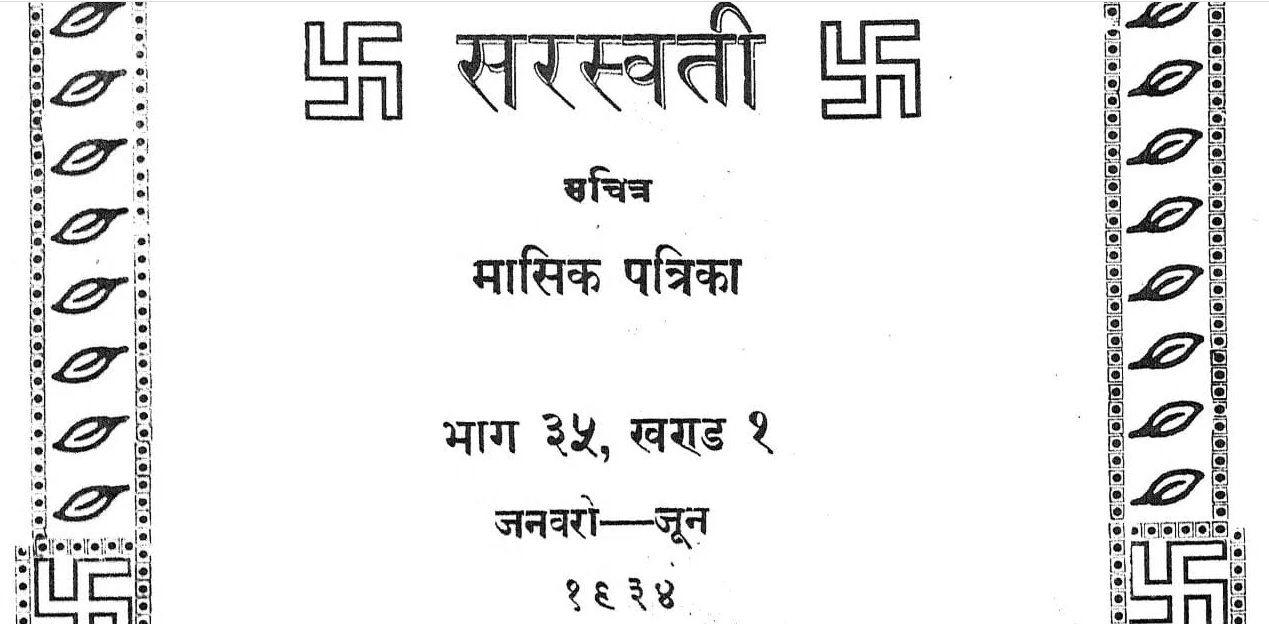

What would have been the objective of Pandit Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi in publishing the Bhojpuri poem “Achhoot ki Shikayat” by a certain Heera Dom from Patna in the magazine Saraswati in the year 1914? This is something that piques my interest. To begin with, in all probability, at the time, Saraswati would not have had a single Dalit reader. How would the Dwij readers have reacted to this poem? Secondly, was this done under the influence of Gandhism? That is unlikely because Gandhi’s “Harijanouddhar” (emancipation of Harijans) programme was still 15 years away. Gandhism started engaging with the Dalit issue in 1932 after the signing of the Poona Pact. Thirdly, was social pressure behind it? That is most likely, for there were enough reasons for that.

Before we go into the reasons, it would be better to talk more about Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi and Saraswati. How did Saraswati happen to lay its hands on Heera Dom’s “Achhoot ki Shikayat”? Why was Heera Dom not introduced to the readers of the magazine? In the diamond jubilee special issue of Saraswati, published in 1961, Heera Dom of Patna is introduced thus: “There is no way of knowing about him. The [manuscript of the] poem just says ‘prapt’ [received]. It is therefore likely that some educated gentleman, after hearing this poem being sung, might have jotted down the words and sent them to Saraswati for publication. What is important is that this poem on emancipation of the Untouchables was published in Saraswati in 1916” (page 805, no 289).

This comment is misleading. The poem was published in 1914 and not in 1916. It was republished in the diamond jubilee issue with 1914 mentioned within parentheses as the year of first publication. I haven’t seen the 1914 issue of Saraswati that carried the poem. But many scholars have confirmed that the poem appeared in that issue. So, we can treat it as a fact that the poem was published in 1914. As for no personal details being given about Heera Dom it may be true that “some educated gentleman, after hearing this poem being sung, might have jotted down the lyrics and sent them to Saraswati for publication”.

Now, the question is, what made Dwivedi publish the poem? Was he was an advocate of Dalit consciousness or Dalit renaissance? That is unlikely because Heera Dom was not the only Dalit poem of that era. There were others, too. But their works were never picked by Saraswati for publication. The real reason was that though Saraswati didn’t have Dalit readers, Dwivedi and the Dwij readers of the magazine were well aware of Swami Achhootanand Harihar’s Dalit renaissance. Swami ji was not only the founder of Aadi Hindu Andolan but was also a Dalit poet and the editor of Aadi Hindu, the first Dalit monthly. Compilations of his poetry, published in 1912, are available. Dwivedi could not have been unaffected by the consciousness that the Aadi Hindu Andolan of Swamiji was creating among the Dalits. This social pressure must have led to the publication of Heera Dom’s poem in Saraswati. Swamiji’s works and Aadi Hindu magazine thus played the biggest role in it.

Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi is often described as the pioneer of renaissance in Hindi literature and the publication of Heera Dom’s poem in Saraswati is cited as proof. But this reasoning is flawed. Religious and social reforms, which are essential ingredients of renaissance, are singularly absent from the literature of that era and from Saraswati. Basically, in literature, it was the age of Hindu revivalism. While Dwivedi was writing Draupadi-Vachan Banawali, portraying women as vile and lowly, Maithlisharan Gupta was singing paeans to Hindutva in his Vyas-Stavan, and still others were writing poems like Vishnu Bhagwan ka Vamnavatar. In contrast, the poets of Dalit renaissance were doubting the existence of god and were putting the incarnations of Vishnu in the dock. This was the real renaissance, brought about by Dalits.

The publication of Heera Dom’s poem in Saraswati was not a coincidence. Equally, the absence of Dalit literature in other literary magazines was also not a coincidence. If Heera Dom’s poem puts a question mark on the concept of Hindi renaissance, it also marks the advent of Dalit consciousness in the contemporary world of Hindi literature. Hindi renaissance ignored this consciousness not because of dearth of Dalit writers but because this consciousness did not suit its proponents.

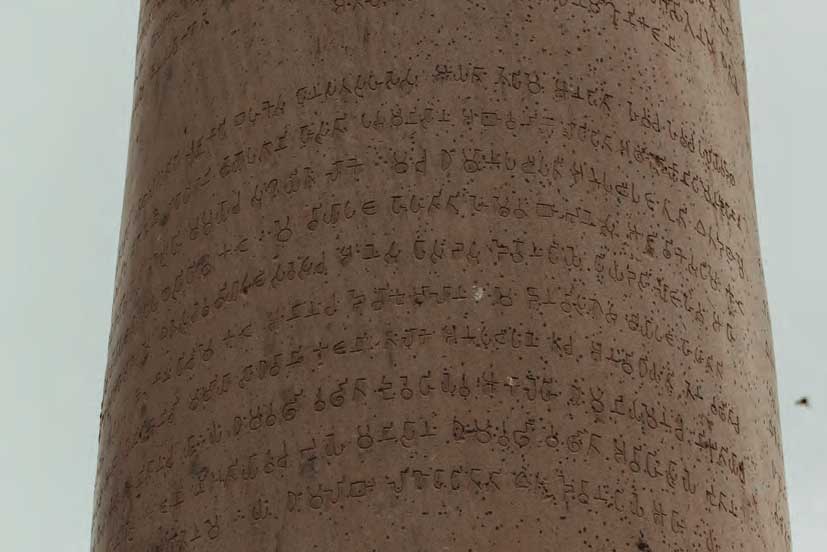

It was Swami Achhootanand’s Aadi Hindu Andolan that was the real movement of Dalit renaissance. This movement was not about fiery speeches. It was a literary movement, centred on social and religious reforms. Swami was a multi-dimensional personality. He was a leader, poet, editor, playwright and social reformer. He wrote poetry on social and historical issues in folk style. He wrote plays like Mayanand Balidan, Ramrajya and Devasur Sangram. The books published by the Andolan were widely read. These books brought about revolutionary consciousness among the Dalit communities. Printing presses owned by Hindus refused to publish their books. Even presses owned by non-Hindus were reluctant, so Swamiji set up his own printing press named Aadi Hindu Press in Kanpur. His magazines Aadi Hindu and Achhoot were printed in this press. How prestigious a publication Aadi Hindu was is evident by the fact that Babasaheb Ambedkar, in his writings, has cited the news items and other information published in it. Could a literary renaissance of this scale have taken place without readers and writers? Swamiji’s writings not only created a huge band of readers but also gave birth to several Dalit writers and social reformers.

For Dalit litterateurs, literature is not a source of entertainment but an ideology that powers revolutions and counter-revolutions. Kabir was the proponent of a literary revolution. Ramcharitmanas represented a counter-revolution against it and is massively publicized even today. Dalit thinkers never wrote for entertainment. They wrote to bring about a revolution. Journalism is also a part of literature. Dalit thinkers had realized the importance of journalism in the 19th century itself. That was why Dalit thinkers in different parts of the subcontinent brought out newspapers. Dr Ambedkar also founded many newspapers that played a revolutionary role in the movement for the emancipation of Dalits.

A frequently asked question is, why non-Dalits cannot write Dalit literature? There is nothing wrong with the question. But we also need to ponder over why Dalits were forced to launch their own newspapers and write their own literature. This question has to be answered before proceeding further. We have find out whether and how Dalit issues figured in non-Dalit literature and journalism. How non-Dalit writers saw the Dalit issues in the past and how they see them today? In my view, it would be best to begin with the literature and journalism of the era of Hindi renaissance.

More than half of the poetry written during the Hindi renaissance hails Ram and Sita and Radha and Krishna. The stories are about the feudals. The remaining one-fourth is about raising consciousness but only to the point where it does not threaten the Hindu Varna system. Up to 1949, Nagarjun was writing a poetical treatise on Ram Katha. Ideologically, the litterateurs of this era were influenced by Dayanand Saraswati of the Arya Samaj and Vedanti Swami Vivekananda, both of whom were supporters of the Varna system. Two leading personalities of this period were Bhartendu Harishchandra and Sitara-e-Hind Raja Shivprasad. Bhartendu Harishchandra is considered one of the pillars of Hindi renaissance by almost all critics. Dr Veer Bharat Talwar, however, disagrees and believes that it is Raja Shivprasad who deserves this title. These are two different ways of looking at the Hindi renaissance. Some of these opinions were shaped by the influence of the British Empire while the others were related to the issue of language. But the Dalits had a different perspective, and Hindi criticism has never attempted to see Hindi renaissance from the Dalit standpoint.

Dalits are conspicuously absent from the Hindi renaissance of both the 19th and the 20th centuries. It is thus clear that the pioneers of this renaissance did not consider the Shudras and the Untouchables as part of the Hindu community. Their fascination for Hindutva and Hindu scriptures is evident from their works. And as such, the plight of the Dalits and the Shudras could hardly have been a matter of concern for them.

The situation was no different in the field of journalism. The problems and issues of the Dalits find no mention all the way from Bhartendu’s magazines to Pratap Narain Mishra’s Brahmin. An article “Videsh Yatra” published in Mishra’s monthly Brahmin (Volume 9, Issue 1, p 13-16) gives us an idea of his beliefs. Opposing foreign travel by Hindus he wrote, “… What is the purpose of crossing the seven seas? It will not take you to a place of pilgrimage and wash your sins off … We don’t know what the point is in travelling to faraway lands and losing invaluable things like time and money, caste, etc. If you are so enamoured of these places, try to get separate ships made for sahbhojis [those who can dine together], try to get Hindu ashrams built there in which you can live with touchable persons and get eatable foodstuff, work for getting the Shivalaya of Londoneshwar constructed and England Bihari consecrated, establish the custom of atonement by visiting sacred places such as Ayodhya and Mathura after your return. If you can do all this, you are free to go.”

A “frog in the well” full of such unscientific ideas doesn’t deserve to be even called a writer. Someone who believes that foreign travel is religiously corrupting can hardly be expected to have any understanding of the Dalit issue.

Dr Veer Bharat Talwar reveals in his research-based work Rassakashi that Pratap Narain Mishra was an obscurantist supporter of untouchability and was dead opposed to social reform. He wanted social reformers punished, so great was his hatred for them! According to Talwar, Bhartendu Harishchandra, Balkrishna Bhatt and other writers and journalists who were considered the pioneers of renaissance were opposed to any kind of social reform or social change. Like the members of the Sangh Parivar today, they were supporters of Hindutva, Varna system and caste-based discrimination, and were anti-Muslim.

How Balkrishna Bhatt looked down on the Dalits is evident in this excerpt from his article in his monthly Hindi Pradeep: “During the revolt of 1857, seeds of bravery sprouted in the hearts of the Koris, Chamars, Dhuniyas, Julahas and Hijras, too. But when it came to action, they could not utter a word except ‘May you be safe’, ‘May your sway last for forever’, ‘May the troubles destined for you befall me’, ‘I survive on your leftovers’, and so on. They escaped to save their lives.” Dr Talwar rightly says, “The conceit of the noble Brahmin class is palpable in this anti-Dalit outburst, which seeks to conceal the selfishness of the Dwij castes that were serving the British for years” (Rassakashi, p 260).

Dr Talwar writes, “The writers of Hindi renaissance opposed every such movement which posed a serious challenge to the caste system” (ibid, p 279). This is not a hollow charge. Their works prove its veracity. It would be naïve to believe that the Hindi renaissance writers were unaware of the 19th-century Dalit renaissance, led by Jotirao Phule in Maharashtra, Chand Guru in Bengal, Narayan Guru in Kerala, Guru Ghasidas in Madhya Pradesh and Achhootanand in north India. They knew about them and that was why they opposed them. But the Dalit writers, journalists and reformers of this era continued to oppose Brahmanism with their full might, without caring for the views of the “Hindu” writers and editors.

(Translation: Amrish Herdenia; copy-editing: Anil)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)

The titles from Forward Press Books are also available on Kindle and these e-books cost less than their print versions. Browse and buy:

The Case for Bahujan Literature

Dalit Panthers: An Authoritative History