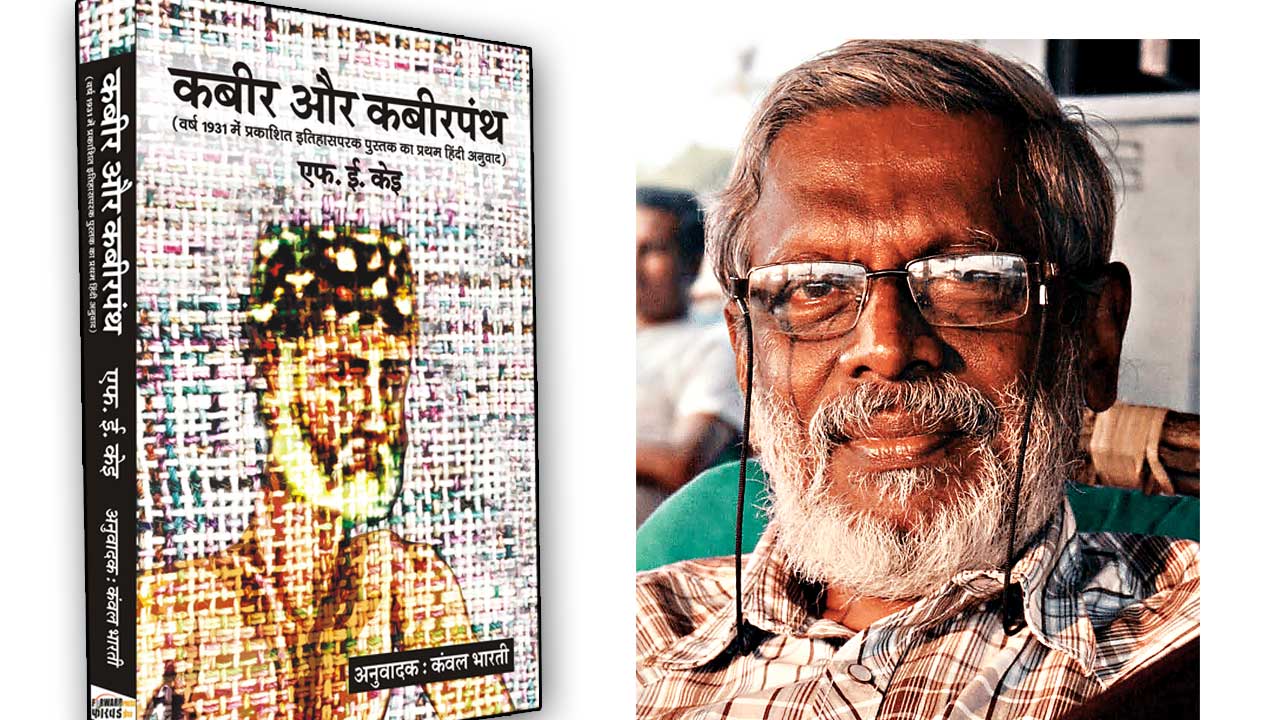

Following is a part of the text of the address by Dr Bharat Patankar at a webinar titled ‘What has been the importance of the critical gaze of outsiders (non-Indians) on Indian society?’ organized by Forward Press on the occasion of the release of the book ‘Kabir Aur Kabirpanth’ (Kanwal Bharti’s translation of ‘Kabir and His Followers’ authored by F.E. Keay) on 20 August 2022

Kabir and Raidas, in a way, were mad after love. Love was central to their writings. Doesn’t Kabir say, “Pothi padh padh jag mua, pandit bhaya na koy, eke aakhar prem ka, padhe so pandit hoy”? This love is not limited to the human race. It pervades all places, it embraces all living beings. This love is for the entire living and non-living world. So, becoming an Indian, though not born one, and becoming a foreigner, though born an Indian, is possible only if we believe in love as enunciated by poets like Kabir and Raidas or even Tukaram. Here, we are talking about loving the entire world and loving the human race. Their poetry was synonymous with this idea of love. In Marathi, it is called “Shahiri”. Their poetry stems from their love – this is a way of seeing life, a way of living life and of expressing yourself while living that life. That expression takes the form of verse or poetry.

People from other countries, that is, countries other than Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, etc, who came here, lived here – why is it that their account of the history and their assessment of the sociopolitical situation of India seems more objective? Why did they write with great love? The reason is that only those who love the people of this country, the history of this country, only they would like to write about India. Secondly, the scholars from outside of the subcontinent are opposed to the caste system that prevails here, the system under which we all were born and we all have grown. They do not believe in the caste system, their objective often resonates with annihilating the caste system.

We should readily accept that caste lurks somewhere in our subconscious mind. It is not readily visible. But our thinking, our writing – it is tinged with caste. For instance, in what kind of Hindi do we write? Many kinds of Hindi are written. In some places, Sanskritized Hindi is used. In other places, words from the regional languages are liberally used while writing in Hindi. In still other places, Hindi borrows freely from Urdu and Farsi. What kind of Hindi one would write often depends on the kind of Hindi one was educated in. That also decides your ideology or the way you think. So, the people who come from outside – they don’t have casteism there. But they do have racism. In some countries they have dynasticism. But casteism is different from racism. In racism, members of a particular race are the rulers. People of other races are treated as slaves. They are ruled upon and exploited. In the caste system, there is a graded hierarchy. So, those from outside, even if they are from the exploited class, who haven’t lived here, cannot wrap their head around the caste system. But in our country there is caste hierarchy even among the exploited sections. Those at the lowest rung of the caste system are treated with disdain even by others of the exploited class, who are perched on a relatively higher rung. Babasaheb Dr Ambedkar calls this complex system a division of labourers. The visitors, who have not experienced the caste system – they see it in a different light. Belonging to a caste, then to a sub-caste, and to further hierarchies of other kinds is not in their subconscious mind. That is why they are not biased in the way they approach the caste system. The concepts they form, the words they use, the way they see exploitation, is different. But a Pakistani will see the caste system in the same way as an Indian. The same will be the case with a person from Bangladesh or Sri Lanka. That won’t be the case with Europeans or Americans. But yes, if they are men, they may have a biased view with regard to exploitation of women. Foreigners, too, may fail to notice the exploitation of women. If they are middle-class, they may also have the biases typical to the middle class. But here we are talking about the casteist society of India.

That is why these visitors’ assessment, their analyses, their theorizations do not suffer from casteist biases. Another reason is it can be said that (in India) history was not written. History is different from mythology. The Bible, the Quran, they have a bit of history. But history is different. Europe and America witnessed a distinct struggle on this issue. There were ideological struggles, there was renaissance. The scholars writing about us have behind them this history of renaissance. And so they are not running away from renaissance in India, too. Gail says that there was a renaissance in India against the caste system. Kabir, Raidas, Namdev and Tukoba were part of this renaissance. This renaissance was subdued. Its reach was limited and its impact was small. These great personalities did engage in a struggle but their struggle could not become a part of the social psyche. So those who are born here are biased. But in Europe or America, this kind of bias is not there. For them, history is distinct from the religious books that form only a part of “history”. This is another reason why their (outsiders’) analysis is comparatively freer from biases. Hinduism’s influence on history and the notion that mythology is history – the researchers /writers from other countries are free from these things. Hence, we say that the outsiders do a better analysis or can do a better analysis or there is a greater possibility of their analysis being better. Of course, this would happen only if they do not come under the spell of Brahmanism while doing their research here.

Talking of Gail and me, our relationship, it was an ordinary husband-and-wife relationship. We didn’t even come to know when and how we became comrades, friends and life partners. There was one element in our relationship: If we talk about it in terms of Tukoba, Kabir and Raidas, love was at its centre – love for mankind or the desire for liberation of mankind or the dream that there should be a city free from sorrows. That was their yearning. Gautama Buddha yearned to end sorrows. This yearning has come to us in poetic form, in a form that touches your heart. It has come from Bhakti saints, from Kabir, from Raidas. This yearning and love being life, as was the case with Kabir and Raidas comes to fruition, when we come together. These were there, so Gail could do it. She could conduct research of different kinds in this country. She did not rely on any document. She went from village to village meeting people. She was the only one who went from village to village for her research. The information she collected had wide ramifications and concerned a large number of people. The conclusions she arrived at were closer to the truth. Gail and I, too, yearned for the society, love that Kabir dreamt about. We had a yearning for that. I still have a yearning for that.

It was because of this that she could do all this work, that we could continue living in our ancestral home. People from Forward Press visited our home. They wrote that it would be difficult to live in that home. Many changes have come about in our village but our home remains more or less the same. We were under the spell of some sort of madness. We wanted to spread love. Domestic problems did not matter at all. This is a way of living one’s life; this is a way of looking at things. That was why Gail could get closer to the truth. So, this is central to becoming an Indian or in deciding what sort of Indian one will become. She could have become an intellectual or spent her life in a university, and yet be an Indian. But she did not become that kind of an Indian. She spent 90 per cent of her time in the countryside. Even when she was in Delhi, or in Shimla, she would take a month’s leave and visit villages or poor urban areas. The lifestyle you choose is very important. If love for mankind is at the centre of your dreams, then it should show in your behaviour, too. Had she not lived the way she did, had she not become one with the people, had she not immersed herself in them, had she not agitated, she would not have been able to contribute as much as she did.

Translated from the original Hindi by Amrish Herdenia

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)