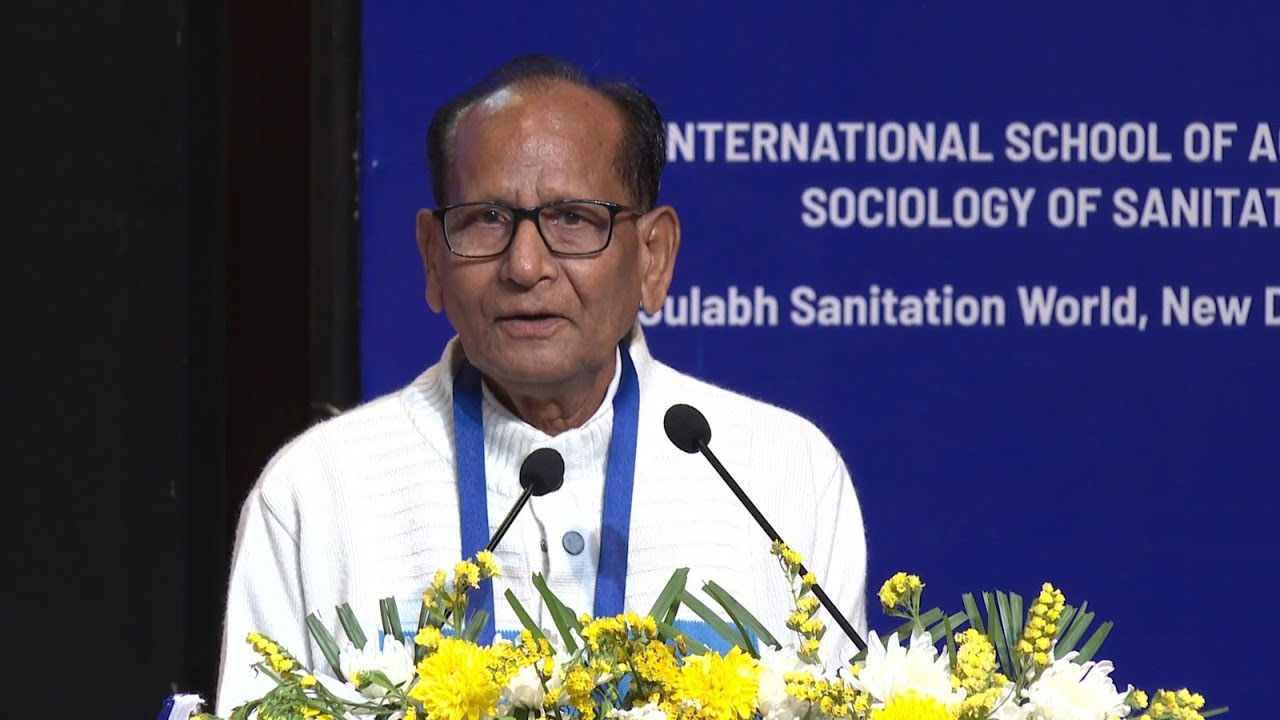

Prof Shyamlal is a sociologist of repute. He has served as the vice-chancellor of Patna University, Patna and Jai Narayan Vyas University, Jodhpur and as acting vice-chancellor of Rajasthan University, Jaipur. Earlier, he was head of Department of Sociology at Rajasthan University. He has also been the chairperson of the Drafting Committee for the Ambedkar Foundation under the Department of Arts, Literature and Culture, Government of Rajasthan. He has authored 21 books and 50 research papers. His published works include his autobiography “Untold Story of a Bhangi Vice-Chancellor” (Rawat Publications, New Delhi), “From Higher Caste to Lower Caste: The Process of Asprashyakaran and the Myth of Sanskritization” (Rawat), “Crisis of Dalit Leadership” (Rawat), “Atrocities on Untouchables” (Rawat) and “Ambedkar and Bhangis” (Rawat).

There have been voices from the Dalit community both welcoming and criticizing the judgment pronounced by the seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court on 1 August 2024 in The State of Punjab vs Davinder Singh. The top court has ruled that the State has the right to create sub-quotas for Scheduled Castes. Professor Shyamlal spoke with FORWARD Press on this issue:

What is your first reaction to the Supreme Court judgment on subcategorization of Scheduled Castes?

It is an important judgment. The judgment has evoked different kinds of reactions in society and especially within the Dalit community. But that happens with every judgment. In fact, with every issue, there are always two sides. One side supports something, another side opposes it. There is nothing new in this. This will happen no matter what the issue is – people will always have different opinions. The Supreme Court judgment has been no different. Now, you may call it controversial or you may not – it is no more controversial than any other judgment or issue. I don’t think there is anything new about how society is reacting to the judgment.

A large section of the Dalits is opposing the verdict. Their argument is that first, this judgment will sound the death knell for the social and political unity of the Dalits. Second, even the provision of reservation that has been on paper for decades is still not being implemented properly and so talking of sub-categorization is meaningless. Your take?

You see, first, to study the reaction in social media about the judgment, we should divide the country into two parts. We should see the reaction with reference to south India and north India separately. As for south India, almost all the politicians have accepted the judgment and have welcomed it. Taking a step further, one state has even announced that it would implement it. As for north India, the reaction has been quite the opposite. The furore is mainly confined to north India.

Second, only a particular opinion is being projected in social media, which is that the judgment would divide the Dalit community into different factions. It seems as if a majority of the Dalits are critical of the judgment. Few have commented on the positive aspects of the judgment. There are very few who have expressed their views in favour of the judgment.

Another thing that I want to say is that when reservation was being implemented for the Dalit community as a whole, people other than the Dalits, the Savarna community, opposed it. Subsequently, too, they kept on opposing it off and on. When reservation for Dalits as whole was being opposed, Dalit leaders and intellectuals argued that if in a family a brother is strong and prosperous and the other is weak and poor and if the weaker brother is given extra food and some additional facilities, he may progress and become equal to his stronger brother. This was the argument our people proffered when the Savarnas opposed reservations. Now, when the Supreme Court has said the same thing about people within the Dalit community, Dalit intellectuals should pause and think.

What we told the Savarnas who opposed reservation for Dalits – why can’t we apply it to the members of our family, to our people? That section of the community, which, due to circumstances, by dint of their hard work and enterprise, has marched ahead of other sections, should definitely introspect. They should say, “OK, we have achieved what we wanted to achieve and you people, due to some reason, or due to the community lacking leadership, or because of lack of numerical strength, have been left behind, so we should think about you.” I believe that if the Supreme Court judgment is viewed from this perspective, many misconceptions that are being spread in society can be removed. This is, of course, my assessment.

How would you interpret the present representation of Dalits in higher education?

Why are you focusing on one dimension? You are talking about appointments to institutions of higher learning. Do you know a journalist once asked Ambedkar what he thought would make it possible for the Dalits and the Backwards to get their rights and opportunities to advance? Dr Ambedkar said that when his people, after acquiring an education, occupy high positions, sit in decision-making positions, then the community at large would definitely get opportunities to advance. Today, there are 300-400 universities in India and among them, if we talk about north India, only a handful have Dalit vice-chancellors or Dalits occupying decision-making positions. I won’t like to comment on south India but on the basis of my experience in north India, I can say with confidence that the Dalits are still being subjected to injustice. There is no doubt about that. I have been the vice-chancellor of three universities. My experience has been that when appointments are made, the Dalit vice-chancellor may have to deal with 18-20 members belonging to other communities in the interview board, but if the vice-chancellor has the willpower, if he is capable of answering the questions that are raised, if he is competent enough to ensure coordination, then he can ensure that appointments are made in keeping with the provisions in the Constitution.

I will give you an example of my university where I was a student and later became the vice-chancellor. Jodhpur University was founded in 1962. I became its vice-chancellor in 1996. From 1962 to 1996, not a single Dalit had been appointed to the university under reservation quota. When I got the opportunity I made appointments in keeping with the Constitutional provisions and the rules of the university and what I did became an example to follow, not only for Rajasthan but also for the entire country. I appointed about 30-40 Dalits to teaching and non-teaching posts. What I mean is that whenever we get a chance, we should take decisions in keeping with the Constitutional provisions and implement them. At the theoretical level, everyone talks of Constitutional provisions. Our people, too, have raised their voice in support of the Constitutional provisions. But the question is why our people are not appointed to decision-making posts.

Then there is this other thing you would be familiar with – ‘Not Found Suitable’ (NFS), which is repeated ad nauseam. If you want to reject someone, you can always think of a dozen excuses. I remember that I was on an interview board. We were holding interviews. A Dalit candidate entered the room. If you permit, I can even name his caste. He belonged to the Sansi caste [liquor-makers and butchers]. He had applied for a clerical position. But his performance was far from ideal. All members of the interview board said that he was not suitable and couldn’t be recruited. When I heard this, I couldn’t help speaking up. I told the chairman, “Sir, just look at the social and educational background of the caste he belongs to. This boy is a Sansi. His community has little to do with reading or writing. He is the first from his community to have completed graduation. Did you or any of us help him when cleared the [school] board exam?” Everyone said, “No, he cleared the exam on his own.” Then I said, “When this boy cleared the BA exam, did we help him?” The answer was a “no” again. He cleared the exam through his own effort. Next, I said, “This boy, after having worked hard to pass the school board and BA exams, is now before this interview board. He now deserves our sympathy, which means we should clear his name.” We should have this sympathetic attitude towards these classes. This is essential.

Also Read: Prakash Ambedkar: Supreme Court got it wrong, State can’t subdivide Scheduled Castes quota

Do you think confining reservations to only one generation will ensure adequate representation of the SCs in the government and the administration? Won’t it take generations to make it up to the top positions – from being a peon or a clerk to becoming an IAS officer or secretary to the government?

You talk of one generation. Suppose there are four brothers in a family. If all of them get the opportunity to acquire an education, if they are granted reservation, then, they themselves definitely will advance. But the social change that we are talking about – that won’t come about within a generation. So, in my view, it is not at all advisable to limit reservations to one generation.

Do you think that this concept of sub-quota is rooted in the upper-caste mindset – that a Dalit should be satisfied with becoming a peon or a clerk?

No. I don’t agree at all. My opinion is that subcategorization is not a bad idea in the sense that if there are certain groups of people in society which have been left behind – they themselves might be responsible for it or there might be other factors – and subcategorization helps them move ahead in life then I am all in favour of sub-quotas. If you don’t subcategorize, how will you give them opportunities? If you don’t want to give them opportunities by subcategorization then you have to find another way of doing so. And that method should be such that it benefits them. So, in the given circumstances, if special provisions are made for them through subcategorization, what is wrong with that? What is the harm? In my view, there is nothing wrong with the concept of subcategorization per se.

Do you believe that there are class divisions within the Dalits? For example, if there is a Jatav district collector or a Jatav secretary to the government, then will he have the interest of all Dalits in mind or will he only look out for Jatavs? What role will sub-quotas and subcategorization play here?

You see, I am basically a student of sociology. I have also been a researcher. I have also been a teacher. Then, I have also played the role of an administrator in universities. So, the insights, the experiences I have gained by working in these different positions and also the literature I have read as a researcher or later as a teacher and what I am reading now after retirement – all of this tells me that it is a psychological fact that no person can disengage himself from his caste or community. Whether you talk of the Savarna mindset or the Dalit mindset, you cannot seek a solution to any problem without taking caste into account. Whether the issue is social or political or cultural – it invariably involves caste. If there are castes within the Savarnas, there are castes within the Dalit community, too. Caste has penetrated so deep into our mindset that we simply can’t shrug it off. There was a PhD thesis that was submitted to Meerut University. It was a study of four-five Dalit castes. It covered Valmikis, Chamars, Khatiks and also Raigars. So, the researcher studied these four-five castes and found that they have many shared values. But he also found that there are separate water taps in the clusters housing these castes. Raigars were not allowed to use the water tap of another caste, the Valmikis were not allowed, and so on. He also found that even those who had abandoned their traditional occupations and had joined other fields, did not like to interact or dine with people from castes they considered lower than theirs. This is a reality. Like the hierarchy we see among the upper castes – from higher to lower – there is a hierarchy among the Dalits too. Dalits, too, now have their own Brahmins. They behave just like the upper-caste Brahmins do. This is something you will find in every caste. Also, it is human nature that if a person from a particular caste occupies a decision-making position, he has a soft corner for people from his caste. And that is natural. It is a part of the human psyche – you can’t do away with it no matter how hard you try. Yes, you can reduce its quantum, its intensity. He can favour his caste or community to some extent but broadly, he can be neutral. This is feasible.

Don’t you think the Supreme Court’s judgment is an assault on the legacy of Dr Ambedkar, on his legacy and his thinking pertaining to the Dalit identity?

No. Just tell me how it is an assault on the ideology of Ambedkar. You just can’t say something offhand. How is it an attack? Can you explain? I don’t agree that it is an attack on (Ambedkar’s) ideology. If a section of society hasn’t been able to progress for some reason and if we are talking about helping them advance, then we are talking about our people. We are not talking about any other caste or community. Yes, the “Not Found Suitable” argument is there, but to treat it as an excuse to not take measures to help those left behind among the Dalit community to progress would be doing injustice to them.

(Translated from the original Hindi by Amrish Herdenia)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)