The film Vedaa, directed by Nikkhil Advani, released on 15 August. The film caught my attention for apparently incorporating a theme that not only Bollywood but also regional-language cinema hubs often have shied away from: caste-based oppression. Although the film was a commercial project, it failed to perform at the box office, especially in comparison to the simultaneously released Stree 2, which achieved significant success. This raises the question: Are audiences still not ready to accept such content, or did the film’s makers and star cast not promote it with the enthusiasm needed to reach a wider audience?

The film’s narrative is set in a dystopian environment and revolves around its titular character, a Dalit girl named Vedaa (played by Sharvari Wagh). However, the story seems to focus more on Major Abhimanyu Kanwar (John Abraham), who is declared guilty by a court martial for disobeying orders after his wife is killed in Kashmir. Seeking solace and a new purpose in life, he takes up a position as an assistant boxing coach in his late wife’s hometown, Barmer, in Rajasthan. His arrival coincides with Vedaa’s journey towards empowerment.

The film lays out Gandhi’s vision for India, particularly concerning the place of Dalit women in society, and in doing so, perhaps unwittingly, reveals the dichotomy with Ambedkar’s vision. It explores casteism, patriarchy, untouchability, surnames, love, education, and Rajput feudalism.

In an early montage, Vedaa Bairwa is seen looking into a mirror, which also has a small photograph of Dr Ambedkar stuck at its corner. Moments later, Vedaa is shown gazing at a large statue of Gandhi on her college campus. This visual juxtaposition raises important questions. Veda comes from an educated Dalit family, where Dr Ambedkar, is present within the home as a marginalized figure, while Gandhi serves as an inspiration in the public sphere and as a moral compass for the narrative. This is how the film begins – by emphasizing Gandhi’s reformist ideas in religion and society, while entirely omitting the contributions and perspectives of Ambedkar.

Earlier too, Bollywood has exploited the landscape of Rajasthan and incorporated Dalit stories as marginal narratives, but Vedaa stands out by centring a character with the surname Bairwa, a Dalit, even titling the film after her. While there could be debate about how central her character truly is beyond her name appearing as the title, the producers deserve praise for this effort.

Vedaa is portrayed mostly as a docile and perpetually dependent character who speaks only occasionally. Her communication is “less verbal and more gestural”, with downcast eyes and a subdued voice. She aspires to be a boxer, but this decision leads to her being beaten and mutilated by members of the Thakur (Rajput) family. She seeks refuge with Abhimanyu Kanwar, with the narrative appearing more focused on Abhimanyu’s journey as a “one-man army” and “macho man” and advancing the story from his perspective. Vedaa serves simply as a narrative device.

Vedaa’s family is acutely aware of their caste’s position in society. Her father is a law graduate, and Vedaa and her sister are studying at Vishwakala Arts and Law College in Barmer. Despite their education, Veda is forced to drink from a separate water pot designated for Dalits at her college. When the pot is empty, she has to ask “upper caste” students to fill water for her from the water cooler. After being beaten by the Thakur Pradhan’s younger brother and his goons, she goes to Abhimanyu, silently shows him her wounds, and when he offers her water from a glass, she refuses, instead staggering to drink from the pot reserved for Dalits, even in her injured state.

Upon returning home, Vedaa asks her sister, “Why are we Shudras beneath their feet?” Her sister, referring to the Thakur Pradhan’s words, says that it is an arrangement imposed from above (the will of the divine). Vedaa retorts, “Then why are we studying law? Why do they make us swear by the Constitution? Why not just teach us this arrangement directly?” Throughout this conversation, the film repeatedly cuts to scenes of Abhimanyu boxing in anger, as if venting his frustration at Vedaa’s plight. While this could be seen as an attempt by the director to convey nuance, the portrayal of Vedaa adhering to caste codes even in a state of distress strains credibility, especially since Abhimanyu, who sees himself as a liberal atheist, does nothing to stop Vedaa drinking from the pot reserved for Dalits.

The narrative closely parallels Anubhav Sinha’s Article 15, where an “upper caste” outsider, IPS officer Ayan is ignorant of the caste-based discrimination in rural areas. Similarly, in Vedaa, Abhimanyu, a suspended army major and an “upper-caste” outsider unaware of the caste dynamics, becomes a messiah-like figure who desires to bring change and fights for the Dalits.

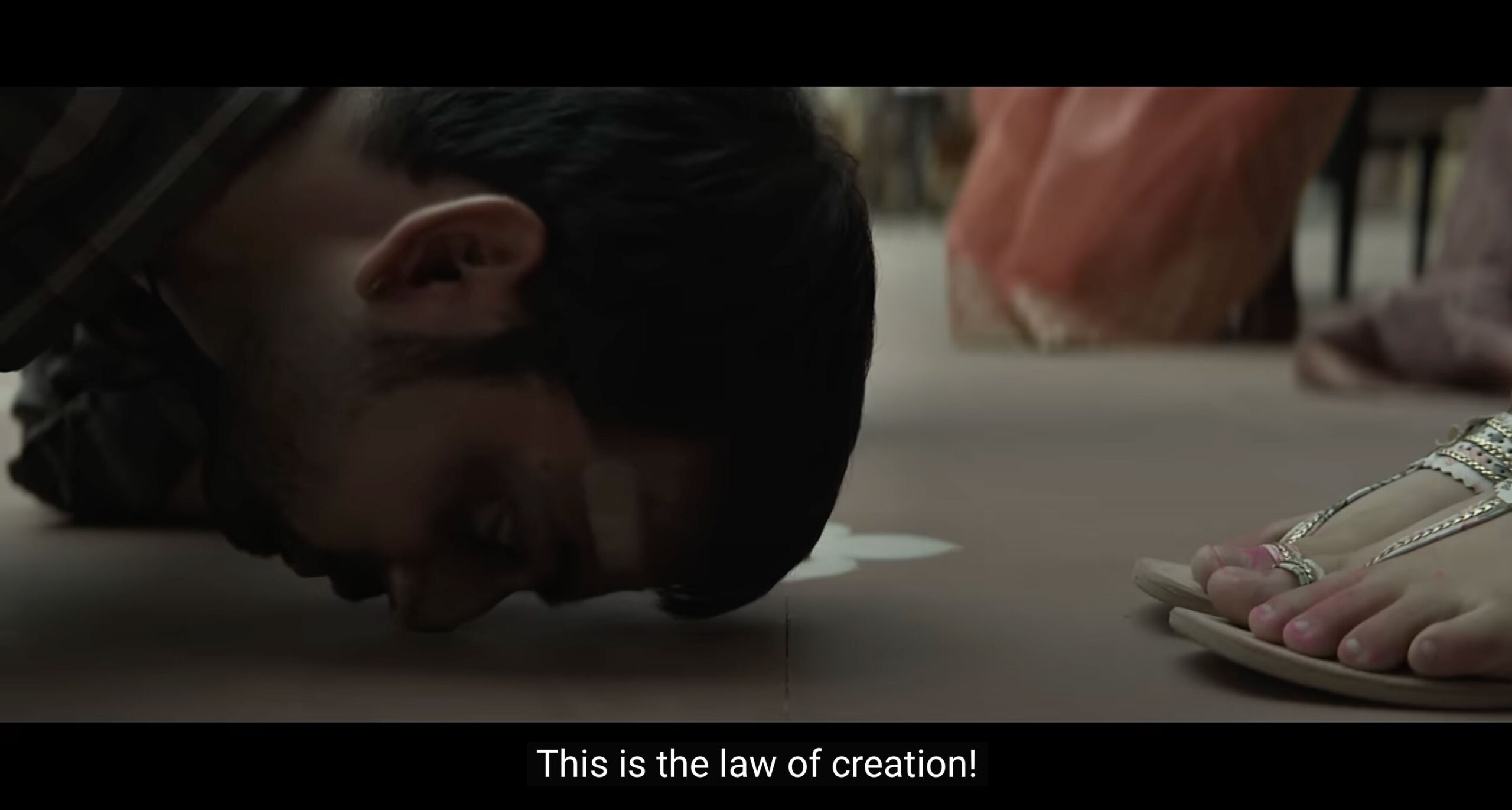

Vedaa’s brother is in love with a girl from the “upper caste” Khandelwal community. When their relationship is discovered, the Thakur Pradhan humiliates the entire Bairwa family at the Khap panchayat (caste council) by forcing them to place shoes on their heads and making the brother rub his nose in the dirt at his lover’s feet. When the couple later elopes, the Pradhan pretends to support them but ultimately has them both murdered after their marriage.

When Vedaa and her sister flee to save their lives, the Pradhan and his henchmen pursue them. Vedaa manages to take shelter with Abhimanyu, but her sister is caught and burnt alive by the goons. Abhimanyu takes Vedaa to the Pradhan’s haveli and challenges him. Then as he is taking her to her relative in another village, Vedaa declares that there is no point in going there as they won’t help. They have never stood up for anyone, why would they stand by her now? She asks. This shows that despite the growing solidarity among the Dalit community, the protagonist feels isolated. She is depicted as a vagabond, lacking any community ties, which is why Abhimanyu emerges as her saviour. Even her uncle, a retired army officer, who initially pretends to assist her, ultimately turns out to be an informer for the Pradhan. This situation seems to suggest that the true empowerment needed within the Dalit community has not yet been achieved, despite their educational and economic advancements.

Vedaa herself pleads in court and demands justice for her murdered brother and sister, citing the failure of the police to help her. She requests that her complaint be registered under Article 226 of the Constitution of India, Section 482 of the CrPC, while Abhimanyu continues to fight the Pradhan.

She concludes her statement by saying, “It’s my fault that I was born a Dalit, and worse, a woman. These people, who avoid even touching us, will never let us live.” She appeals to the judges, saying that all she wants is her right to live with dignity – “all we want is to breathe”.

The film poignantly highlights the condition of Dalit women, who are doubly oppressed because of their caste and gender. A critical moment in the narrative occurs when Vedaa briefly speaks up about her legal rights. However, the film portrays her character in a manner that reinforces her dependence and docility. Even in this scene, she appears as a helpless figure, pleading rather than asserting herself. Throughout the film, Vedaa the character never fully develops an assertive voice capable of expressing the profound pain and anger resulting from the injustice and oppression she has undergone. This depiction contrasts starkly with the contemporary Dalit movement, which demands rights rather than begging for them. The judges are shown cowering as Vedaa speaks, before a female judge finally agrees to hear her case.

The film invokes Mahabharata using “Abhimanyu”, which is originally a character in the epic. While Abhimanyu of “Vedaa” is initially portrayed as an atheist, by the end of the film, he is reciting a verse from the Bhagavad Gita. He tells the Thakur Pradhan, who repeatedly refers to him as a Mahabharata character, “If you had read the Mahabharata properly, you would know that the wrath of a woman, her dishonour, can bring down entire regimes. I am just the charioteer; the one who will break the Chakravyuh is inside [referring to Vedaa], and she will destroy your fake regime.” This represents another attempt to reinterpret the Mahabharata within a modern framework, particularly by repositioning women within religious narratives where they have been “glorified”.

When the Thakur Pradhan asks Abhimanyu what he gained from all this, Abhimanyu replies, “What I couldn’t gain by taking lives, I gained by saving one.” The Thakur then points a gun at him, but Abhimanyu turns the gun on the Thakur and kills him. The film ends with text appearing on the screen informing the audience that Vedaa is inspired by the case of killing of newlyweds Manoj and Babli for marrying within the gotra, in Kaithal, Haryana, in 2007 after a Khap Panchayat passed an order to that effect and another incident in 2015 in which a Khap Panchayat in Baghpat, Uttar Pradesh, passed an order that Meenakshi Kumari and her sister be raped and paraded naked for their brother eloping with a higher caste woman.

The final scenes show Abhimanyu as Vedaa runs towards him. When she reaches him, she realizes that he is dead. She weeps, and the film cuts to her father in the background. He is portrayed as a figure of sacrifice for the greater good. More text appears on the screen, which cites The Hindu newspaper stating that in 2011, the Supreme Court while hearing the case of Arumugam Servai vs. State of Tamil Nadu described the institutions like Khap Panchayats as “kangaroo courts”, declaring them entirely illegal and ordering their strict abolition. There is yet another message clarifying that the Vedas describe all humans as one caste and that any division is based on “Varna”, which is a classification based on occupation alone.

In this context, the film, through its narrativization and visualization, operates on two levels. On the one hand, the film is titled “Vedaa”, based on its Dalit character’s name, which signifies the Vedas (brahmanical scriptures), and defends the Vedas. On the other hand, the film appears to criticize the inhuman caste-based discrimination perpetuated by “upper-caste” individuals. Ambedkar argued that dismantling the caste system requires the destruction of these brahmanical scriptures which form its basis. But this film, while superficially criticizing the caste system, favours the Vedas and attempts to situate the entire narrative within the brahmanical religious framework.

The director’s attempt to create both a conventional Bollywood film and a social drama has resulted in failure on both fronts, as the two aspects feel like entirely different films. The inclusion of the item song and other musical sequences appears clumsy and disrupts the flow of the narrative. This film exemplifies the Gandhian “upper caste” saviour gaze, in which the Dalit characters, particularly women like Vedaa, remain marginalized within their own narrative. “Vedaa” reflects the persistence of caste hierarchies even in the telling of a story meant to challenge them.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)