Raidas was a modern thinker and writer, both in terms of his thinking and its expression. Critical thinking is often cited as the cornerstone of modernity. In simple terms, it involves a critical appraisal of the contemporary dominant ideologies and sensitivities, as also the social, cultural and religious conditions and inter-relations; it means challenging dominance and subjugation in all their forms. It also means making the common man – and not god or king – central to thinking and writing, and making argument and reason – rather than faith – the point of departure for looking at and understanding issues. It also includes a belief that there is nothing like luck or fate, and that what happens to you is solely the consequence of your own actions. Critical thinking also means evaluating a person not on the basis of their religion, caste or family but solely on their virtues. It also means making experienced reality, not what books say, the basis of one’s writings or beliefs. And lastly, it means having the courage to challenge and reject the religions and scriptures that confer supremacy on specific groups and the social relations this hegemony translates into.

Raidas was a modern thinker in all these terms. The importance he accorded to toil and the toiler makes him out to be a Marxist. We can trace the basic elements of Ambedkar’s views on the varna-caste system in the writings of Raidas, who lived some 400 years before Ambedkar.

In Indian society, the feudalism-versus-modernity struggle manifested itself in the struggle between Brahmanism on the one hand and the Bahujan-Sramana tradition on the other hand. Let us delve into the modern thinking of 15th-century Raidas with the help of his writings.

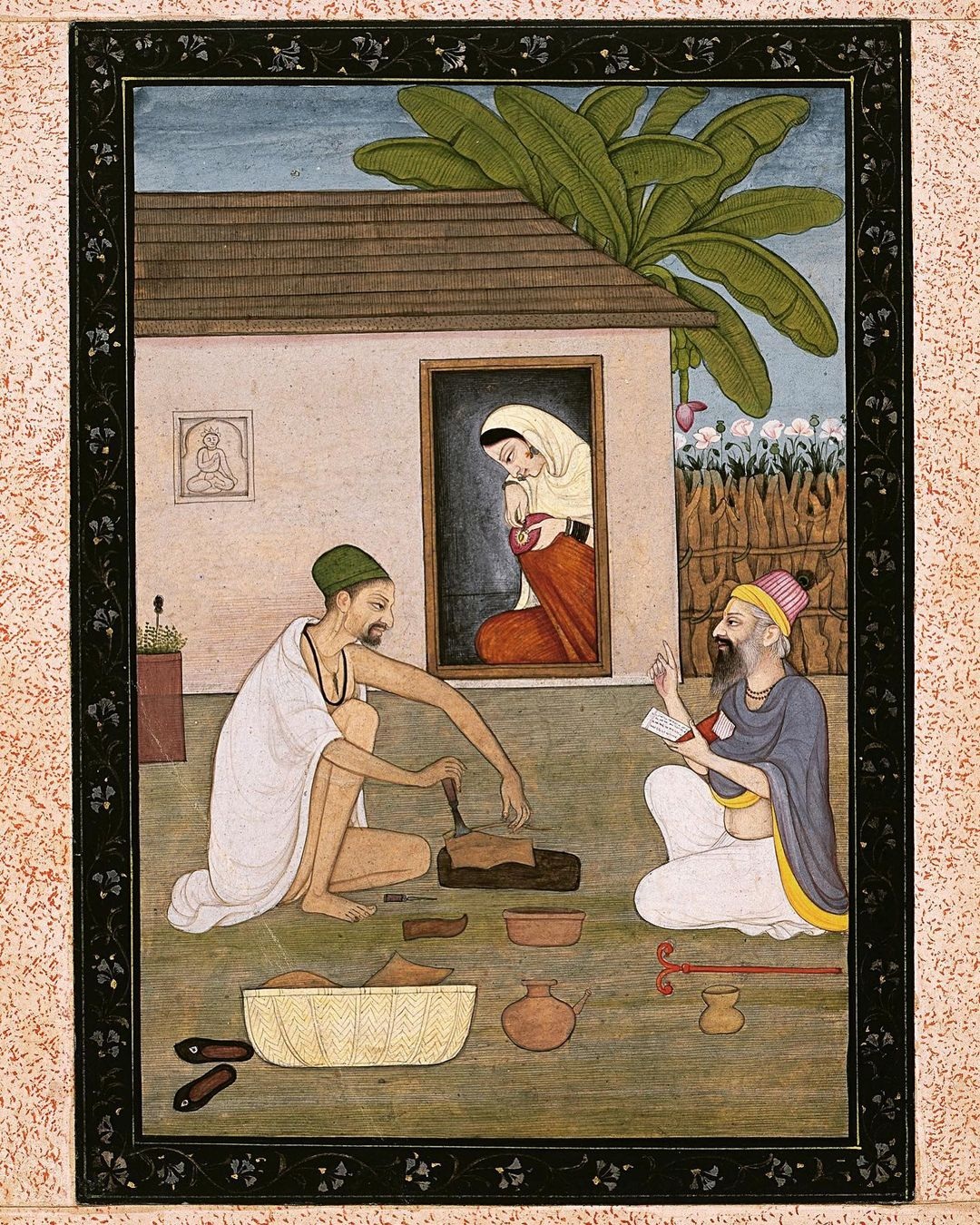

Importance to work and workers

In the West, it was Marxism that brought labour and labourers centre stage. Those who believe that work and workers was the pivot of the growth of humanity are called by different names, including socialists and communists. Raidas makes it clear that the toilers are superior to the Brahmins – who claim to be gods on earth.

Dharam karam jaane nahin, man mah jati abhiman,

Aey sou Brahman so bhalo Ravidas shramikahu jaan

Describing the workers as higher than the parasitic Brahmins, and that too in the 15th century, must have required some courage. In Indian society, Brahmins represent the class that abhors work. The pyramid of hierarchy fashioned by the Brahmin authors of brahmanical texts rests on the negation of work. The more critical the work of an individual or a group is to society, the lower it is placed in the brahmanical texts and epics. Mehtar is considered the lowest because he does the essential work of cleaning. The Antyaja are considered the fifth and the lowest Varna because they toil in the fields. The Shudra are considered lowly because they are farmers and artisans.

But Raidas insists that having one’s meals only after working is the highest value. He insists that one should eat only after one has worked.

Raidas shram kari khayeeheen, jaun laun paar basaay

Nek kamayi jau karayi, kabahoon na nihphal jaay

The socialist or communist society that the leftists dream to build – or where they have successfully built such societies – lays great stress on every healthy individual contributing to production directly and not living off the toil of others. Those who live off the toil of others are called parasites. They are blood-suckers and are despised and reviled.

Raidas lays great stress on freedom and terms servitude a sin.

Paradheenta paap hai, jaan lehu re meet,

Raidas das paradheen saun, kaun karai hai preet

The Indian Bahujan-Sramana tradition has always accorded pride of place to work and workers. Ambedkar named his first party as the Independent Labour Party. In contrast, India’s brahmanical (feudal) tradition eulogizes parasites. Raidas belongs to the Dalitbahujan tradition and believes in the culture of work. He believes that one should not eat without working. Raidas himself toiled to earn his livelihood and for him, living on the wages of one’s labour was the highest value. In his view, leaving one’s home and family and turning an ascetic was nothing but hypocrisy.

Nek kamayi jau karayi taji ban nahi jaaye

In contrast, the dwij castes have not only been enjoying the fruits of the labour of the Dalitbahujan but they wear their parasitism as a badge of honour and as the underpinning of their superior position in the social hierarchy. They believe that industry is inversely related to one’s station in life – the less you work, the higher you are; and the harder you work, the lower you become.

Raidas and varna-caste based social order

The varna-caste system has been the determinant of the economic, social, cultural and religious relations in India, as well as the foundation of the feudal social order. That remains unchanged to date. Raidas analyzes it in-depth and rejects it completely, just like a modern thinker would do. He argues that birth does not make a person lowly; lack of sensitivity and compassion does.

Daya dharma jinhen mein nahin, hriday paap ko keech

Ravidas jinahi jani ho, maha paatki neech

The medieval feudal order, on the other hand, did not treat virtues as the marker of the greatness of a person or a group. Your greatness was determined by the caste, religion or family of your birth. Tulsidas expressed this sentiment succinctly.

Poojahin vipra sakal gunheena

Sudra na pujahin gyan praveena

Raidas believed that a person should command respect on the basis of his deeds. The accident of birth cannot make a person worthy of reverence. Like Buddha, Kabir, Phule, Ambedkar and Periyar, Raidas unambiguously insists that it is deeds, and not birth, that make a person high or low.

Raidas janm ke karney, hot na koye neech,

Nar koon neech kari dari hai, ochhe karam kee keech

In the preface to the second edition of his Annihilation of Caste, Ambedkar writes, “I shall be satisfied if I make the Hindus realize that they are the sick men of India, and that their sickness (of caste) is causing danger to the health and happiness of other Indians.”

Four hundred years before Ambedkar, Raidas said the caste system was a disease that had destroyed the humanity of Indians. The caste system does not allow a person to remain human. People from one caste don’t see those from the other castes as equals. They see them either as lower or higher. Raidas says that only the demise of caste can bring about the birth of humanity.

Jaat paant ke pher manhi, urjhee rahayi sab log

Manushta koon khaat hayi, Raidas jaat kar rog

Ambedkar, too, repeatedly asserted that India cannot become a nation and Indians cannot become free and equal brothers without the annihilation of varna and caste.

Raidas echoes the same view:

Raidas na manush jud sake, jab laun jaye na jaat

Raidas says caste has divided Indians into umpteen parts. There are castes within castes

Jati-jati mein jati hai, jyon kelan mein paat

Ambedkar also makes the same observation repeatedly in his writings.

Hinduism, Islam and Raidas

Raidas says in unambiguous terms that he has nothing to do either with a temple or a mosque because god lives in neither. He does not differentiate between the Hindus and Muslims and exposes the hypocrisy of both.

Masjid son kuch ghin nahin, mandir son nahin piar

Doh manh Allah Ram nahin, kahai Raidas chamar

Raidas keeps away from temples and mosques. But he loves both Hindus and Muslims.

Musalman son dosti, hinduon son kar preet

Raidas joti sabh ram kee, sabh hain apne meet

Raidas repeatedly asserts that there is no difference between Hindus and the Muslims. The elements that make a Hindu are the same as the elements that make a Muslim. They are born in the same way. Both are flesh and bones.

Hindu turuk mahi naahi kachhu bheda duyee aayo ek dwar

Praan pind lauh maas ekahi Raidas vichar

Here it would be pertinent to mention that modernity and atheism are not synonymous. Kant, Hegel, Thomas Paine, Voltaire, Rousseau, Jotirao Phule – none of these modern thinkers who reshaped the world were atheists. If you make atheism an essential condition for being modern, most of the modern thinkers will not meet the criterion. So, you cannot study the thinking of Raidas based on whether he was a theist or an atheist. Or, if he believed in god, what role he gave to the Almighty in the world. Kant, a great modern philosopher, could analyze the world without rejecting the concept of god. Jotirao Phule’s god could not stop him from making logical, scientific thinking; reason; and justice the bases of his ideas and beliefs.

It is a thinker’s concept of the State that delineates the core of his thinking. It hinges on whether he dreams of a Ram Rajya based on the varna-caste system and patriarchy, or whether he conceptualizes Begumpura, a realm that exemplifies equality and prosperity for all. Raidas’ utopia is Begumpura.

There are two main sources of pain and misery for any individual, society or nation. The first is the lack of resources to meet essential needs and second, being subjected to inequality, injustice or discrimination. In modern political jargon, they are called economic and social needs respectively. The first is about having the minimum resources to keep body and soul together and second is about dignity and respect. Raidas has listed the essential elements of the utopian Begumpura in just two lines:

Aisa chahoon raj mein, jahan milai saban ko anna,

Chhote bado sab sam basai, Raidas rahe prasann

The two lines succinctly describe humanity’s dream world. The first line says that everyone should have food. Here, food represents all the basic physical needs. The second says that there should be no high and low and that all should live as equals. These two things, Raidas says, would make him happy.

Unlike Tulsidas’ Ram Rajya, based on Varnashrama Dharma, Raidas’ Begumpura has many similarities with Amardesva of Kabir, Baliraja’s rule of Jotirao Phule, Ambedkar’s Prabuddha Bharat and Marx’s socialist society.

Ab ham khub vatan ghar paya, ooncha kher sada man bhaya,

Begumpura shahar ko nau, dukh-andes nahin tihi thaau

Na tasvees khiraju na malu, khauf na khata na tarsu juvalu

Kaaimu-daimu sada patisahi, daam na saam ek sa aahai

Aavadanu sada mashoor, oonha gani bashi maamoor

Tiu tiu sair karhi jiu bhavai, haram mahal na ko atkave

Kah Raidas khalas chamara, jo us sahar son meet hamara

In this verse, Raidas, while seeking emancipation from the system that prevailed in his times, imagines a society free of sorrow. It is called Begumpura or Begumpur shahar. Raidas says that his ideal is Begumpura – a country where there is no high and no low, no rich and no poor and no pollution by touch. It is a country where no one pays taxes and no one owns property; where there is no injustice, no fear and no persecution. Raidas tells his disciples, “My brothers! I have found such a place, that is a system, which may not exist anywhere but where everything is just. No citizen of this place is second- or third-class; everyone is equal. This country is always happy. The people can go wherever they want to and do whatever business they wish to. There are no restrictions on them on the basis of their caste, religion or colour of skin. The palace (feudal lord) does not come in the way of anyone’s progress. Raidas Chamar says whosoever is a supporter of the idea of this Begumpura is my friend.”

There may be uncertainty about the exact dates of Raidas’ birth and death and researchers may have different views, but there is complete unanimity among the scholars that Raidas lived and wrote in the 15th century. The 15th century is a part of what is called the medieval period of Indian history – a period that was marked by feudalism. How come a modern, radical thinker like Raidas lived in that era?

The following elements play a key role in making one embrace radical and modern thinking.

Class: Whether one comes from the class of toilers or of the parasites. In other words, whether one is from the producer class, which works to produce, or from a class that usurps the produce of others and without playing any role in production, that is without working, leads a happy or even a luxurious life. Raidas came from the toiler, producer class. His class played a key role in shaping him into a modern revolutionary writer and thinker.

Social background: In India, varna and caste determine class. The dwij (Brahmin, Kshatriya and Vaishya) lead a luxurious life without contributing to production. The Shudra and Antyaja have been the productive and the toiler classes. The dwij enjoyed a good life by usurping the produce of the Shudra and Antyaja. A big chunk of the dwij is doing so even now.

Ideological heritage: Raidas’ thinking was rooted in social realities, but at the same time was modern and revolutionary. His ideological heritage is a part of the Bahujan-Sramana tradition. The roots of this ideological heritage run wide and deep. It includes Buddhist, Jain, Aajivak and Lokayat ideologies, which find a place in the works of Siddhas and Naths. Raidas takes this heritage to new heights.

Raidas was born into the working class. He lived by the sweat of his brow and was a thinker and writer. He was born a Dalit – a community which was humiliated and stigmatized to no end. We can also say that he was born into India’s most revolutionary class-varna, which had inherited the radical beliefs of the Aajivaks, Buddhists, Lokayats, Siddhas and Naths. These three elements made Raidas a modern radical thinker-writer in the feudal medieval era.

He was opposed to inequality and injustice in any and every form. In that sense, he leaves the modern European thinkers and writers miles behind. Almost all the modern European (French, British, German) and later American thinkers and writers supported injustice and inequality in one way or the other. When they talk of equality, they don’t talk about universal equality. When they talk about rights, they don’t talk about universal rights. For them, equality, justice and rights are meant only for particular sections or people. Raidas, on the other hand, wants justice, equality and dignity for everyone. A comparison between Raidas and modern European thinkers would merit considerable elaboration and should wait for another time. For now, only two instances would suffice. The French Revolution raised the slogan of liberty, equality and fraternity, but in practice, its liberating impact was limited to only the propertied, literate and white men. Similarly, the American Revolution of 1776 talks of human rights and even incorporates them in the Constitution. But these rights are meant only for white men. The Negroes, the Blacks and the women would continue to remain shackled. Here, we are talking about the 18th century. The European thinkers-writers of the 15th century never even talk about equality, liberty and fraternity. Their pronouncements were like the Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam slogan of Indian Brahmins. The entire world comprises their brothers, but Indian Shudra, Antyaja and women – who form a majority of the population – are lowly creatures.

Finally, why hasn’t Raidas’ radical thinking and his works got wider national and international acceptance? In fact, his modern vision hasn’t even accorded the place it deserved in history. This had to do with the brahmanical-feudal thinking and colonial mindset. The stream of brahmanical-feudal thinking has been and is dominant in India. Indian academia (including universities) has always been dominated by these forces. They could not have identified, let alone accepted, the radicalism and the modernism in Raidas’ works. They can’t do so even today. At the most, they can dub him a saint-poet and usher him into the club of the likes of Ramanand, Ramanuj and Tulsidas. They can study and teach Raidas only as a saint-poet. Had they accepted him as a modern radical thinker-writer who challenged Brahmanism and feudalism, they would have run the risk of not only erasing their own ideological tradition, but also of social tumult – a cultural-ideological revolution.

The colonial mindset is another reason why Raidas’ radicalism has not been appreciated and highlighted. The 200-year-old slavery of the British has made Indian intellectuals prone to searching the roots of all radical and modern thinking in European and American writers, thinkers and philosophers. The dwij intellectual and writer, steeped in Brahmanism and a feudal and colonial mindset, could not have accepted that India gave birth to a modern radical thinker way back in the 15th century. It would have been impossible for them to swallow the fact that he was from the working class and a Dalit.

(Translated from the Hindi original by Amrish Herdenia)

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)