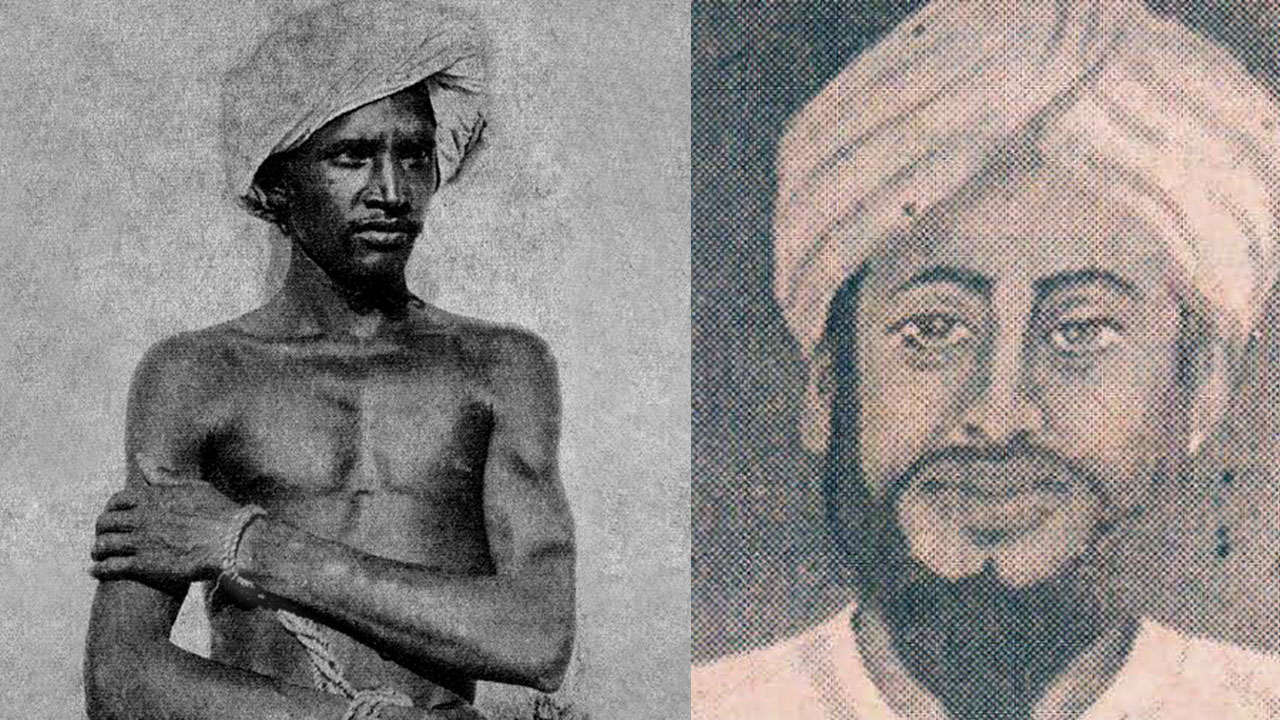

In 2025, India stands at a historic crossroads, commemorating two monumental milestones: the 134th birth anniversary of Dr B.R. Ambedkar and the 75th anniversary of the Constitution coming into force. This is a profound juncture to reflect on the nation’s democratic journey, its unfulfilled promises, and the enduring relevance of Ambedkar’s radical vision. Born into the stigmatised Mahar caste in 1891, Ambedkar emerged as a colossus of modern India – a jurist, economist, feminist, and the principal architect of a Constitution that sought to dismantle centuries of caste tyranny. As India celebrates its 75 years of constitutional governance, his warnings about the “life of contradictions” between political equality and socio-economic inequality echo with unsettling urgency.

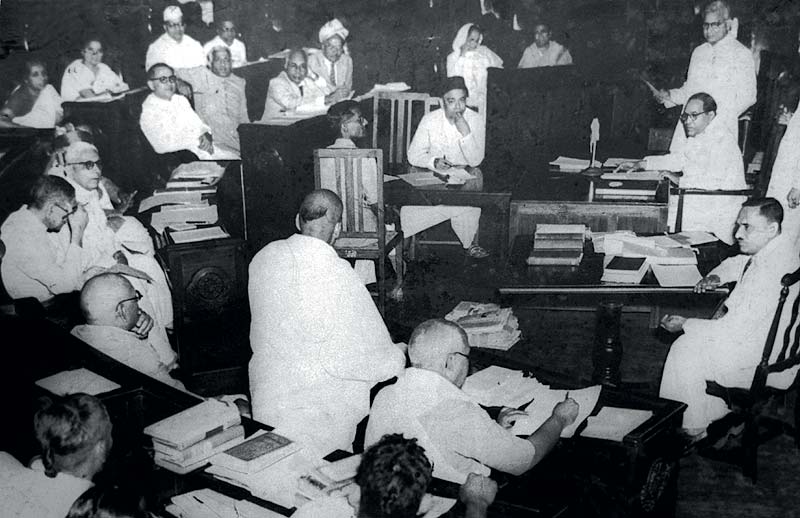

It is now 75 years since India’s Constitution came into force on 26 January 1950, a document Ambedkar described as a “social contract” to redeem the nation from the “grammar of caste”. Its adoption was revolutionary: a post-colonial democracy granting universal adult suffrage from its inception, either enshrining or allowing for affirmative action for the historically oppressed communities (Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes). Yet, Ambedkar’s closing speech to the Constituent Assembly in 1949 struck a cautionary note: “We must make our political democracy a social democracy as well. Political democracy cannot last unless there lies at the base of it social democracy.”

Dr Ambedkar’s 134th birth anniversary is a call to confront these contradictions. His life – a saga of battling caste apartheid, drafting the Constitution, and ultimately renouncing Hinduism to embrace Buddhism – embodies the struggle to reconcile legal equality with social equity. As the architect of India’s affirmative action framework, he recognized that formal equality was insufficient to dismantle caste’s “graded hierarchy”. His vision demanded substantive equality – redistribution of land, education and political power to Dalitbahujan communities. Today, as India debates caste-based censuses and wrestles with the intersection of technology and inequality, Dr Ambedkar’s ideas offer a roadmap to bridge the constitutional promise with ground realities.

In this context, while Dr Ambedkar is celebrated as the Constitution’s chief draftsman, his legacy transcends this role. He was a polymath whose contributions spanned economics, gender justice, and philosophy. As an economist, he critiqued Brahmanical capitalism in The Problem of the Rupee (1923) and advocated for land reforms to dismantle feudal structures. As a feminist, he drafted the Hindu Code Bill in the 1950s to grant women property rights and divorce protections – a bill so radical that it triggered a backlash from conservative MPs, leading to his resignation as law minister. Though the bill was diluted, its principles later shaped progressive laws like the Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act (2005). His magnum opus, Annihilation of Caste (1936), remains a blistering indictment of Hinduism’s caste system, arguing that “applying the dynamite” to the religious texts that sanction it was a prerequisite to political democracy.

In the global context, Dr Ambedkar’s ideas resonate with movements for racial justice, intersectional equity, and human rights. His correspondence with W.E.B. Du Bois in the 1940s revealed a shared vision for dismantling systemic oppression, with Dalitbahujan activists today drawing parallels between caste apartheid and anti-Black racism. Yet, Western academia often marginalizes Ambedkar, favouring Eurocentric thinkers like John Locke or Rousseau.

Ambedkar as democracy’s unsung hero

Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s vision of democracy transcended the simplistic notion of majority rule. He critiqued majoritarian democracy as a system that risked perpetuating the tyranny of dominant groups over marginalized communities. For Dr Ambedkar, democracy was not merely procedural – it demanded substantive equality, where historically oppressed castes, women, and religious minorities could live with dignity and could access resources and power. Unlike formal equality, which treats all citizens identically regardless of systemic disadvantages, substantive equality requires proactive measures to compensate for historical injustices. This principle underpinned his advocacy for reservations (affirmative action) and land redistribution.

Central to his democratic philosophy was constitutional morality – the idea that constitutional values must permeate societal consciousness, not just exist as legal texts. He warned against reducing democracy to elections, emphasizing, instead, cultivation of ethics like fraternity, accountability, and respect for dissent. His insistence on minority rights stemmed from his lived experience of caste apartheid; he argued that democracy’s strength lay in protecting the weakest, not empowering the majority. This vision of social democracy – a fusion of political rights with economic and social justice – challenged India to move beyond symbolic freedoms. “Democracy is not merely a form of government,” he asserted, “It is primarily a mode of associated living.” As Chairman of the Drafting Committee, Dr B.R. Ambedkar embedded his democratic ideals into India’s constitutional DNA.

- Fundamental Rights: Articles 14-18 guarantee equality before the law, prohibit discrimination, and abolish untouchability (Article 17), directly targeting caste hierarchy.

- Directive Principles: These non-justiciable guidelines (Articles 36-51) prioritize social welfare, workers’ rights, and equitable resource distribution, balancing individual liberty with collective welfare.

- Affirmative Action: Articles 15(4) (after the first amendment in 1951) and 16(4) enabled reservations for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes, operationalizing his belief that historical oppression demanded reparative justice.

Dr Ambedkar’s genius lay in reconciling competing imperatives. He defended free speech (Article 19) while allowing reasonable restrictions to prevent communal harm. He championed federalism but advocated for a strong centre to unify a fragmented post-colonial society. His defence of the Hindu Code Bill – aimed at granting women property rights and outlawing polygamy – highlighted his commitment to gender justice, even amid fierce opposition. However, he cautioned that constitutional rights alone were insufficient: “However good a Constitution may be, if those implementing it are not good, it will prove to be bad.”

Despite the many constraints he faced, Dr Ambedkar’s legal expertise, intellectual acumen, and commitment to democracy allowed him to steer the Drafting Committee toward embedding fundamental values into the Constitution. Under his leadership, the document enshrined ideals such as Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity, a comprehensive framework for Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles, a federal structure with a clear separation of powers, an independent judiciary, and crucial affirmative action policies like reservations.

The Indian Constitution, born from these efforts, became more than just a legal framework – it emerged as the most powerful tool for the Indian people in their fight against oppression, discrimination, and injustice, ensuring that the democratic spirit of the nation remained alive and resilient.

Yet, Dr Ambedkar remains under-recognized in Western and Indian academia, overshadowed by Eurocentric narratives of liberty. His critique of majoritarianism and advocacy for minority rights offer urgent lessons, as democracies worldwide grapple with polarization. In this age of rising authoritarianism, Dr Ambedkar’s insistence on constitutional morality – not just as law, but as a collective ethic – positions him as a global democratic visionary.

Way forward

As India marks the 134th birth anniversary of Dr Ambedkar, it serves as a reminder to re-examine democratic values, inclusivity, and social justice. His principles continue to guide government policies, from educational and economic reforms to social welfare and legal protections. The need of the hour is to mobilize Dr Ambedkar’s ideas to address modern global challenges. Climate justice, ethical AI governance, and reducing global inequalities are areas where his philosophy of social justice can be applied. By integrating his ideals with contemporary governance models, India can lead the world in fostering a just, inclusive, and progressive society.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)