Originally hailing from Assam, Kalpana Patowary carved out a place for herself in the hearts of the people of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh in the year 2000. At that time, the Bhojpuri film industry was undergoing transformation. Post-liberalization, the corporate world had started evincing interest in the industry. It saw in the industry a potential money-spinner. But for want of effective literary intervention, the quality of the films remained poor and songs using double entendres had become the order of the day. Nevertheless, the Bhojpuri entertainment industry was growing at a scorching pace. It was at this juncture that Kalpana entered the industry. She says that when she moved base from Assam to Mumbai to build a career in music and singing, she had nothing apart from her voice. She knew only English and Assamese. Kalpana says the lyrics of the first Bhojpuri song she recorded about 15 years ago went something like this, “Daal, daal ae raja…apan pichkari se hamra rang daal”. (Raja, soak me with the colours from your water pistol). “When I was recording the song, I thought that ‘pichkari’ was just the thing you spray colours with on Holi,” she recalls. “But when, gradually, I learnt Bhojpuri, I realized that, here, ‘pichkari’ had another [vulgar] meaning.”

Originally hailing from Assam, Kalpana Patowary carved out a place for herself in the hearts of the people of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh in the year 2000. At that time, the Bhojpuri film industry was undergoing transformation. Post-liberalization, the corporate world had started evincing interest in the industry. It saw in the industry a potential money-spinner. But for want of effective literary intervention, the quality of the films remained poor and songs using double entendres had become the order of the day. Nevertheless, the Bhojpuri entertainment industry was growing at a scorching pace. It was at this juncture that Kalpana entered the industry. She says that when she moved base from Assam to Mumbai to build a career in music and singing, she had nothing apart from her voice. She knew only English and Assamese. Kalpana says the lyrics of the first Bhojpuri song she recorded about 15 years ago went something like this, “Daal, daal ae raja…apan pichkari se hamra rang daal”. (Raja, soak me with the colours from your water pistol). “When I was recording the song, I thought that ‘pichkari’ was just the thing you spray colours with on Holi,” she recalls. “But when, gradually, I learnt Bhojpuri, I realized that, here, ‘pichkari’ had another [vulgar] meaning.”

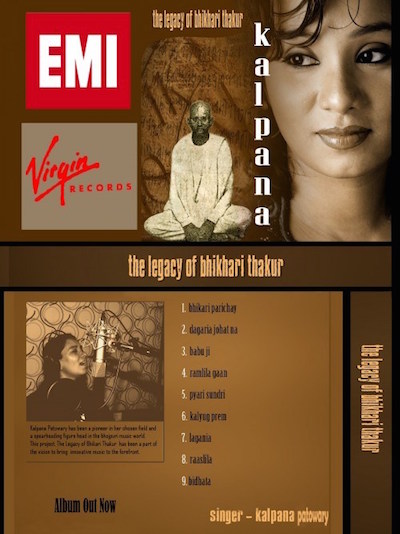

Bhupen Hazarika and Bhikhari Thakur

Kalpana says she learnt music by listening to Bhupen Hazarika’s songs. He was a rebel artiste who never compromised his principles and used music to purge society of its evils. Bhikhari Thakur did exactly the same in Bihar through his writings. He came down heavily on the evils of contemporary society. This was the most important thing they had in common. Kalpana says that a few years ago, at the global launch of her album The Legacy of Bhikhari Thakur, the information available on Thakur on the internet was sketchy. “But now, if you Google Bhikhari Thakur, the search engine will throw up hundreds of links,” she says. Kalpana describes how she had to battle hard to extricate Thakur and his literary works from the social, casteist biases so deep-rooted in the collective psyche of Bihar. When she was doing her research on Bhikhari Thakur, she was often told that Thakur’s literary works were nothing to write home about and that he was not worth researching into. They advised her to concentrate on Vidhyapati and Mahendra Mishra instead. “But by then, I had understood the social reality of Bihar and could guess why Bhikhari Thakur was given short-shrift by the litterateurs of the state. I did not budge from my stand. For me, his struggle was akin to the struggle of Bhupen Hazarika. For instance, in his famous song Ganga tu behti hai kyon, Hazarika poses some searching questions. He does not confine himself to the pollution in the Ganga. Rather, he raises questions on politics, the social set-up and neo-liberal capitalism. Bhikhari Thakur does the same in his play Ganga Snan. He fearlessly hits out at social evils. His every work carried a message for society. For instance, his play Gabarghichor alludes to feminist identity and the rights of women. What is there to talk of that era when women still do not enjoy the rights advocated by Thakur. In Videsiya, Bhikhari Thakur scripts the pain of migration. And this is only one aspect of his writings. The other aspect is that he developed his own style, discarding the traditional music dominated by the elite. His attempt was ridiculed by the elite. His plays were mockingly referred to as ‘Launda Naach’ [Gay dance]. This underlines the social resistance he had to face.”

Tradition goes global

Kalpana says her objective was to fulfil the dreams of Bhikhari Thakur vis-à-vis the wellbeing of Bhojpuri speakers. Thakur chose music as his medium. “Bhojpuri gave me name and fame”, she says. “That is also why I consider it my duty to enrich the language.” After she presented a programme based on fusion of Birha and contemporary music on MTV, she was contacted by a South Africa-based musical group. The Indians, whose ancestors had gone to South Africa as indentured labourers generations ago, are trying to rediscover their roots. They have chosen “Birha” as one of the mediums to connect to their roots. Today, Bhikhari Thakur’s writings need no introduction in Guyana. Kalpana says she has been recently invited to participate in the “S-H 97 Bacardi Musical Programme”, in which she will present “Birha” and Bhikhari Thakur’s Launda Naach all over the country with A.R. Rehman and the international musical group Yami.

Kalpana has no doubt that Bhikhari paid the price for hailing from the Hajjam (OBC) community. All of us should introspect whether the caste or religion of an author is a factor while evaluating their works. Kalpana says artistes like Bhupen Hazarika and Bhikhari Thakur were way ahead of their times. In one of his works, Bhikhari Thakur wrote that 100 years hence, people would recognize and accept him. And that is already happening.

Published in the October 2015 issue of the FORWARD Press magazine