Tamil Nadu, a state known for its vibrant political landscape, stands on the cusp of a significant transformation. As we approach the 2026 assembly elections, the political chessboard is being reset, with new players emerging and old alliances being redefined. At the heart of this evolving scenario is the Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi (VCK), a party that has traversed a remarkable journey from its origins as a radical Dalit movement to becoming a potential kingmaker in state politics.

This article explores the changing face of Tamil Nadu politics, examining the rise of the VCK, the challenges faced by traditional powerhouses like the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), and the emergence of new political forces. We will analyze the historical context, recent developments, and future possibilities that could reshape the state’s political landscape.

The Rise of VCK: From Radical Roots to Political Prominence

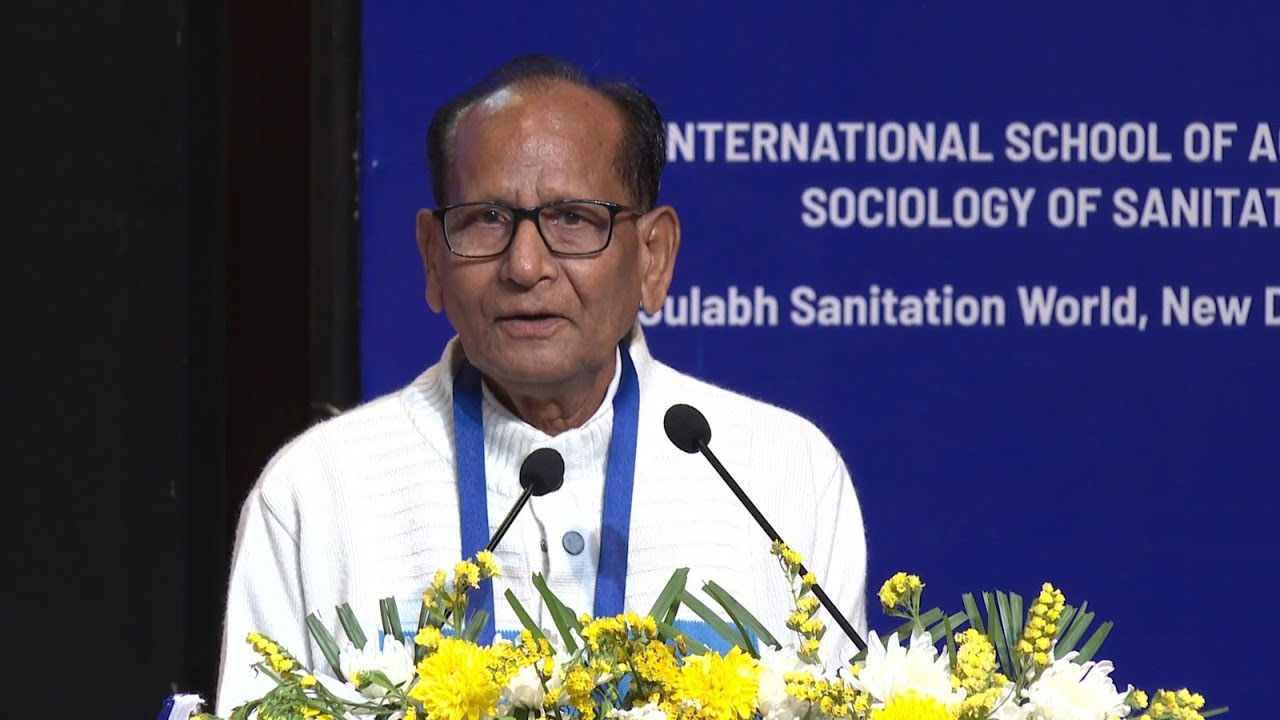

The story of the VCK is one of transformation and resilience. It began as a movement in the 1980s inspired by the Dalit Panthers of Maharashtra, which in turn was inspired by the Black Panther movement in the United States. Under the leadership of Thol. Thirumavalavan, the movement initially advocated boycotting elections, positioning itself as a revolutionary force outside the mainstream political system.

The early years of the movement under Thol. Thirumavalavan (1990s) coincided with significant social and economic changes in Tamil Nadu. The effects of globalization, industrialization and urbanization were beginning to be felt, particularly in the creation of metropolitan centres like Chennai. These urban spaces offered a degree of protection from the harsh caste discrimination prevalent in rural areas, allowing a new generation of Dalits to access education and employment opportunities.

As noted by Professor Hugo Gorringe in his extensive studies on the VCK, this period marked a crucial juncture for Dalit politics in Tamil Nadu. Young Dalits, having experienced life in urban centres, returned to their villages with a heightened awareness of their rights and a lower tolerance for caste-based discrimination. The Dalit Panthers were well-positioned to capture the imagination of this energized youth, providing a platform for their aspirations and anger.

Testimonials collected by Gorringe vividly illustrate the impact of the movement:

“With Thirumavalavan we thought that freedom had come – there is no doubt about that,” said X-Ray Manickam in a 2012 interview.

Stalin Rajangam, another interviewee, stated, “In the last hundred years, no other movement has emerged as a strong movement like the VCK which created uprising among Dalit people.”

“We now have someone to speak for us” was a recurrent refrain and, together with the rising stature of the VCK as a party, this has infused Dalits with a real sense of capacity and dignity.” (Hugo Gorringe, Panthers in Parliament, Oxford University Press, 2017)

For instance, the VCK flag has become more than just a party symbol. It represents the Dalit community’s resistance, assertion, and empowerment. While the flags of other parties may at best resonate only with their cadre, the VCK flag holds a deep personal meaning for the Dalit community as a whole, embodying their growing influence and sense of dignity.

The transition from a social movement to a political party and entry into electoral politics marked a new phase in the evolution of VCK. This shift was not without controversy, with some critics accusing the party of diluting its radical stance. However, Thirumavalavan and the VCK leadership saw it as a necessary step to effect change from within the system.

The VCK’s journey in electoral politics has been marked by both challenges and successes. While the party has struggled to win a significant number of seats on its own, it has become a crucial ally for the major Dravidian parties, particularly the DMK. This alliance strategy has allowed the VCK to have a voice, though limited, in governance while maintaining its distinct identity and ideology.

The Political Landscape: A Historical Perspective

To understand the current political dynamics in Tamil Nadu, it is crucial to examine the results and implications of recent elections, particularly the 2016 and 2021 assembly elections, as well as the 2024 parliamentary elections.

The 2016 Tamil Nadu Assembly Elections marked a significant turning point in the state’s political landscape. The results were as follows:

AIADMK Alliance:

Seats won: 134

Vote share: 41.8%

DMK Alliance:

Seats won: 97

Vote share: 39.3%

People’s Welfare Front (PWF) – (only including VCK, Communists, and MDMK)[1]:

Seats won: 0

Vote share: 3.2%

These results are significant for several reasons:

1. Narrow Margin: The vote share difference between the AIADMK and DMK alliances was a mere 2.5 per cent, highlighting the importance of alliance management in Tamil Nadu politics.

2. Impact of the PWF: The formation of the People’s Welfare Front, which included the VCK, proved to be a critical factor in the DMK’s defeat. In 89 constituencies, the margin of victory was less than the PWF’s vote share, indicating that a united opposition could have changed the outcome.

3. Stalin’s Miscalculation: This was the first election with M.K. Stalin fully in charge of the DMK’s campaign strategy. His decision not to accommodate parties like the VCK in the alliance proved costly, a lesson that would shape future alliance negotiations.

The 2016 election results underscored the importance of alliance-building in Tamil Nadu’s new political landscape. It demonstrated that even parties with a relatively small vote share could play a decisive role in determining electoral outcomes.

The political dynamics shifted significantly in the lead-up to the 2021 Assembly Elections. The key factors influencing this election were:

1. Anti-BJP Sentiment: The campaign was primarily focused on opposing any alliance the BJP was part of. This narrative limited the bargaining power of smaller parties like the VCK, who were vocal critics of the BJP.

2. United Opposition: Learning from the 2016 experience, the DMK managed to keep intact its alliance forged in the lead-up to the 2019 General Elections, which included the Congress, the CPI, CPI (M), VCK and other smaller parties.

3. AIADMK’s Internal Challenges: Following J. Jayalalitha’s death, the AIADMK faced internal power struggles, weakening its position.

The results of the 2021 Assembly Elections reflected these factors:

DMK Alliance:

Seats won: 159

Vote share: 45.7%

AIADMK Alliance:

Seats won: 75

Vote share: 40%

The DMK Alliance’s sweeping victory – albeit with a vote share difference of less than 6 per cent – was attributed to effective alliance management, anti-incumbency against the AIADMK government, and the successful framing of the election as a referendum against the BJP’s influence in Tamil Nadu.

The 2024 Parliamentary Elections: Continuity of the Anti-BJP Narrative

The 2024 Lok Sabha elections saw a continuation of the political alignment from 2021. The DMK-led alliance, which included the VCK, won all 40 seats (39 in Tamil Nadu and 1 in Puducherry). This sweeping victory was facilitated by two major factors:

1. The split between the BJP and AIADMK, which divided the opposition vote.

2. The continued resonance of the anti-BJP narrative in Tamil Nadu

These successive electoral victories have solidified the DMK’s position, but have also created new challenges for the DMK and raised expectations of its allies like the VCK.

Challenges Facing the Major Players

As we look towards the 2026 Assembly Elections, both the DMK and AIADMK face unique challenges that could reshape the political landscape.

DMK

1. Succession Politics and Allegations of Dynasty Rule: The recent elevation of Udhayanidhi Stalin, son of Chief Minister M.K. Stalin, to the position of Deputy Chief Minister, has reignited debates about dynasty politics both within the DMK and beyond. This move has been particularly unpopular among the youth, who question the preference given to a newcomer over more experienced leaders.

The perception of dynastic succession is not new to the DMK, but it gains renewed significance in the context of changing voter demographics and increasing political awareness. One young man expressed this sentiment: “My grandfather voted for Karunanidhi, my father voted for Stalin, so should I really cast my vote for his grandson Udhayanidhi? And just for kicks, should my son get ready to vote for Udhayanidhi’s son Inbanidhi as well? After all, why not keep the family tradition alive?” This response reflects the general mindset of the younger generation.

Udhayanidhi Stalin’s rapid political ascent presents both an opportunity and a challenge for the DMK. While it secures the party’s future leadership, it also risks alienating long-time party workers and second-rung leaders who may feel sidelined. Moreover, Udhayanidhi’s relative inexperience could be a liability if the DMK loses power in 2026, potentially making it difficult to hold the party together in opposition.

2. Managing Alliance Expectations: The DMK’s sweeping victories in recent elections have been largely due to effective alliance management. However, the demand from allies for more significant roles in governance and a larger share of power is likely to increase, putting pressure on the DMK to balance its own interests with those of its allies. The growing calls for a coalition government from alliance partners like the VCK present a dilemma for the DMK. Acceding to these demands could dilute the DMK’s power, but refusing could strain alliance relationships and potentially lead to defections.

Challenges for the AIADMK

1. Leadership Vacuum and Internal Factionalism: Following J. Jayalalithaa’s death, the AIADMK has struggled with leadership issues and internal power struggles. While Edappadi K. Palaniswami (EPS) has emerged as the party’s leader, he still faces the challenge of uniting various factions and establishing himself as a leader of Jayalalithaa’s stature.

2. Rebuilding Party Image: The AIADMK needs to rebrand itself and present a clear alternative to the DMK. This involves not only criticizing the present government but also articulating a compelling vision for Tamil Nadu’s future.

3. Alliance Strategy: The decision to sever ties with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was a strategic move to eliminate the perception of being subservient to a party that many view as anti-Tamil. Additionally, the BJP’s reliance on Hindutva politics does not resonate with the people of Tamil Nadu. However, the AIADMK now needs to build new alliances to effectively challenge the DMK-led alliance.

4. Edappadi Palaniswami’s Future: For EPS, the 2026 election is crucial. A loss could potentially end his political career and further fragment the AIADMK. This personal stake might push him to consider unconventional alliance strategies, such as the rumoured offer of the post of Deputy Chief Minister to Thirumavalavan of VCK.

The VCK Factor: A New Force in Tamil Nadu Politics

Amid these challenges faced by the major parties, the VCK has emerged as a potentially decisive force in Tamil Nadu politics. Several factors contribute to the VCK’s growing influence:

1. Consistent Ideological Stance: Unlike the Dravidian parties that have been accused of diluting their ideological positions, the VCK has maintained a consistent stance on issues such as caste annihilation, social justice, and opposition to Hindutva politics. This ideological clarity appeals to a section of voters disillusioned with mainstream politics.

2. Grassroots Presence: The VCK’s origins as a social movement have given it a strong grassroots presence, particularly among Dalits. This cadre-based structure allows the party to mobilize supporters effectively during elections and on social issues.

3. Thirumavalavan’s Leadership: Thol. Thirumavalavan’s charismatic leadership and oratorical skills have been crucial in maintaining the party’s relevance. His ability to articulate complex social issues in accessible language has won him admirers beyond the party’s traditional base.

4. Strategic Alliance Politics: The VCK has shown adeptness in navigating alliance politics, aligning with different formations based on the political climate. This flexibility has allowed the party to punch above its weight in terms of political influence.

5. Evolving as a Trusted Ally: The VCK has emerged as a trusted ally of minority communities, instilling a sense of safety and confidence amid the rising tide of Hindutva. Consequently, minorities are more inclined to support any alliance that includes the VCK, which not only secures Dalit votes but also draws in a substantial portion of minority votes. This is significant because Dalits (20 per cent) and minorities (12 per cent) together constitute about a third of Tamil Nadu’s population.

6. Expansion Beyond Dalit Politics: While remaining committed to Dalit empowerment, the VCK has broadened its appeal by taking stands on various issues affecting Tamil Nadu, from environmental concerns to linguistic rights.

The Aadhav Arjuna Episode: Catalyst for Change?

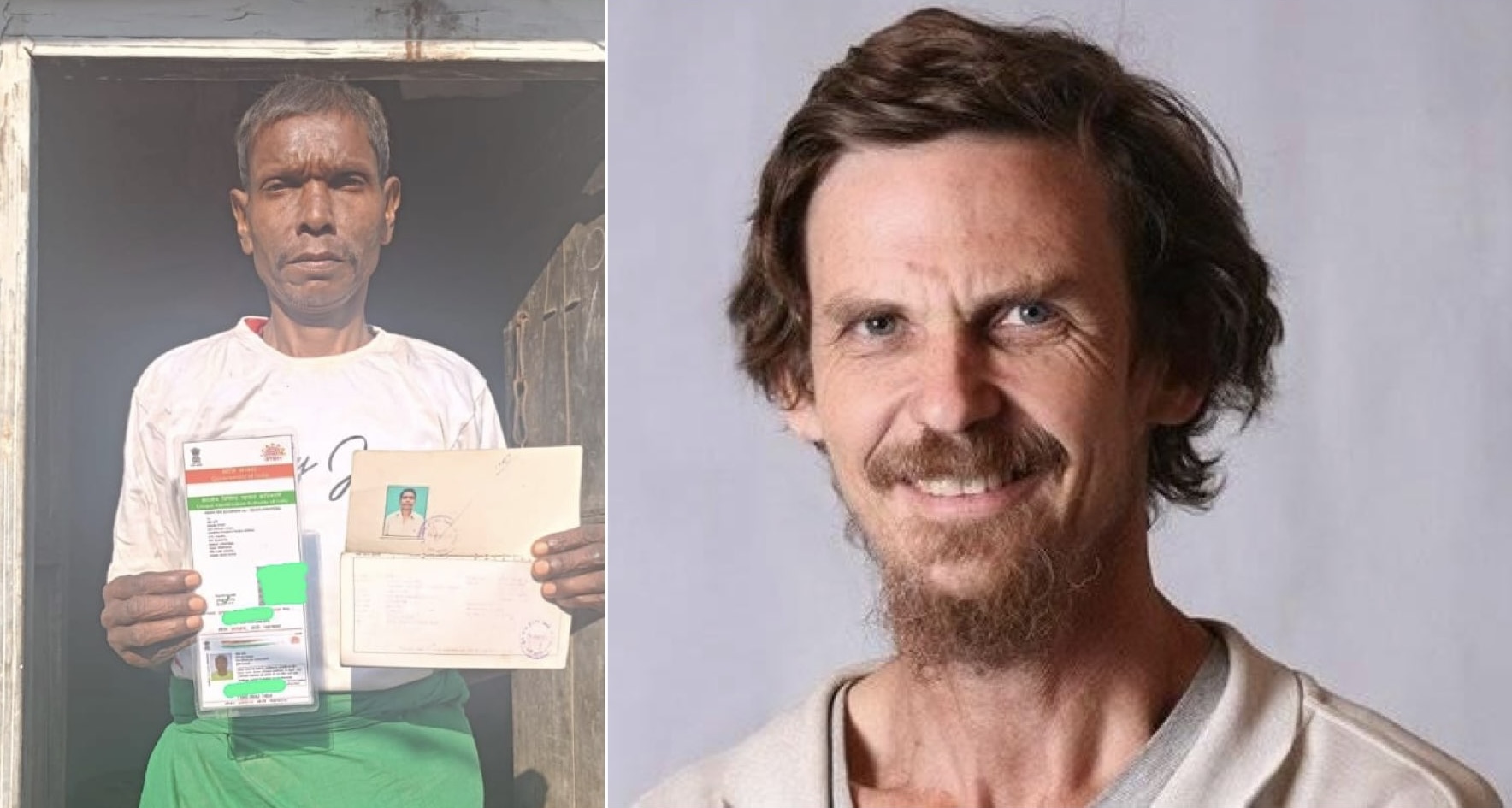

The recent statements by VCK’s Deputy General Secretary, Aadhav Arjuna, calling for Thirumavalavan to be considered for the post of Deputy Chief Minister, have added a new dimension to Tamil Nadu’s political discourse. Arjuna is the son-in-law of Santiago Martin, chairman of Future Gaming and Hotel Services Private Limited, who was in the news earlier this year when it was revealed that he was the among the largest donors to political parties, including the BJP and the Congress, most of his donations going to the DMK and the Trinamool Congress. Arjuna has also been part of IPAC, the political consultancy firm founded by Prashant Kishore, and has been an election strategist for the DMK. Perhaps, given this background of Arjuna, his views are taken seriously by the DMK.

This episode is significant for several reasons:

1. Voicing Cadre Aspirations: Arjuna’s statements resonated strongly with VCK cadres who have long felt that their party’s contributions to the DMK alliance have been undervalued. By articulating this sentiment, Arjuna has given voice to a growing discontent within the party ranks.

2. Strategic Timing: The demand comes at a crucial juncture when both the DMK and AIADMK are vulnerable. The DMK is grappling with succession politics and accusations of dynasty rule, while the AIADMK is still finding its footing after the death of Jayalalithaa and parting ways with the BJP.

3. Broadening Appeal: Arjuna, being a non-Dalit, raising this demand helps in portraying the VCK as a party with a broader appeal – beyond its traditional Dalit base. This could potentially attract a wider spectrum of voters who are looking for alternatives to the two major Dravidian parties.

4. Media Attention and Agenda Setting: Arjuna’s statements have generated much interest and kept the VCK in the media spotlight, allowing the party to set the agenda for political debates leading up to the 2026 elections. This increased visibility could translate into greater bargaining power in future alliance negotiations.

5. Internal Dynamics: The differing responses from VCK’s second-tier leaders to Arjuna’s statements have highlighted potential internal divisions within the party. While some leaders like Ravikumar, Vanniyarasu, and Sinthanai Selvan expressed reservations, Thirumavalavan’s tacit support for Arjuna has reinforced the latter’s position.

At this juncture, it’s important to address the rumours that the party’s second-tier leaders are on the payroll of the DMK and would split the party if Thirumavalavan severs the alliance. However, this claim can’t be farther from the truth, as explained in the “Paradox of Parali Puthur” chapter of Hugo Gorringe’s book “Panthers in Parliament”, based on extensive research and study of the VCK.

The Parali Puthur case study[2] provides valuable insights into the party’s internal dynamics, particularly the centralization around Thirumavalavan and the challenges faced by second-rung leaders. This example, along with interviews conducted by Gorringe, suggests that while there may be internal criticisms and challenges within the VCK, the party’s unity is not necessarily threatened by external influences or payoffs.

6. Capitalizing on Cadre Frustrations: Arjuna’s demand appears to be a calculated move that taps into deep-seated frustrations with the DMK among the VCK cadre. These frustrations stem from several key issues:

a) The Vengaivayal incident, in which human faeces were found in a water tank used by Dalits, and the inadequate response from the government.

b) The state’s reluctance to enact a separate law against honour killings, despite long-standing demands from the VCK and other Dalit rights organizations.

c) The brutal murder of K. Armstrong, Ambedkarite leader and state president of Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and the controversy surrounding his burial, which many VCK supporters saw as disrespectful and indicative of continuing caste discrimination.

d) The perceived hurdles placed by the DMK-led government’s machinery in erecting VCK flag posts. This is seen not merely as an administrative issue affecting the VCK, but as a direct attack on Dalit assertion and dignity. The flag posts are powerful symbols of Dalit empowerment, and any perceived obstruction is interpreted as an attempt to suppress Dalit voices.

e) The perceived ill-treatment of the VCK during seat-sharing negotiations with the DMK, with the former feeling undervalued despite its significant contribution to the alliance.

These issues have collectively created a sense of disillusionment among VCK cadres, many of whom are now more open to the idea of leaving the DMK alliance. Aadhav Arjun, likely aware of this sentiment through grassroots surveys and analysis, seems to be leveraging the discontent to push for greater recognition and power-sharing within the alliance.

7. Pressure Tactic: By voicing these demands publicly, Arjuna and the VCK leadership are effectively putting pressure on the DMK. The threat of potentially leaving the alliance, backed by genuine cadre frustration, strengthens the VCK’s negotiating position.

8. Long-term Strategy: Beyond immediate gains, this episode could be part of a longer-term strategy by the VCK to position itself as more than just a junior partner in the alliance. By demanding the Deputy Chief Minister post, the party is signaling its ambition to play a larger role in Tamil Nadu’s governance.

The Call for Coalition Governance: A New Political Paradigm?

The VCK’s advocacy for coalition governance and power-sharing represents a potential paradigm shift in Tamil Nadu politics. This call challenges the traditional model of single-party dominance that has characterized the state’s politics for decades.

Arguments in favour of coalition governance:

1. More Inclusive Representation: A coalition government could provide better representation for various social groups and regional interests.

2. Checks and Balances: Power-sharing arrangements could prevent the concentration of power in a single party or family, addressing concerns about dynasty politics.

3. Policy Consensus: Coalition governance might lead to more balanced policies as different parties would need to find common ground.

4. Breaking the Duopoly: It could end the cycle of alternating power between the DMK and the AIADMK, bringing fresh perspectives to governance.

Challenges to implementing coalition governance:

One significant challenge is the resistance from major parties like the DMK and AIADMK, which may be reluctant to dilute their power by sharing key positions with allies. However, new entrants in politics like Vijay, the actor, could adopt an out-of-the-box approach, offering a fresh alternative. Additionally, the AIADMK may be compelled to accede to demands, as EPS needs to prove his leadership and effectiveness in a coalition setting.

The Liquor Ban Conference: A Strategic Move

The VCK’s decision to organize a conference calling for a liquor ban in Tamil Nadu on 2 October 2025 (Gandhi Jayanti) was a strategic move that served multiple purposes:

1. Moral High Ground: By advocating for a liquor ban, the VCK positions itself as a party concerned with social welfare, particularly given the tragic Kallakurichi incident in which spurious liquor claimed numerous lives.

2. Challenging State Policy: The demand for closing TASMAC (Tamil Nadu State Marketing Corporation) shops directly challenges the state government’s reliance on liquor revenue, forcing a debate on public health versus fiscal considerations.

3. Broadening Appeal:The VCK’s stance on the issue of alcoholism and its social impact resonates beyond their traditional Dalit base, potentially attracting support from new demographics like women voters and groups the party had not previously engaged with.

4. Media Attention: The conference and the build-up to it kept the VCK in the news, allowing the party to showcase its organizational capabilities and ideological positions.

5. Alliance Building: By inviting all parties interested in people’s welfare to join the conference, the VCK creates opportunities for new political alignments.

Challenges and Opportunities for the VCK

While the VCK’s position seems strengthened, it faces several challenges that it must navigate:

1. Balancing Alliance Politics and Party Growth: The VCK must strike a delicate balance between being a reliable alliance partner and asserting its own identity and aspirations. Too much compromise could lead to disillusionment among its core supporters, while being overly assertive might strain alliance relationships.

2. Broadening Appeal Without Diluting Core Ideology: As the party seeks to expand its base beyond Dalits, it faces the challenge of appealing to a broader electorate without diluting its core ideological commitments.

3. Internal Cohesion: The differing responses from second-tier leaders to Arjuna’s statements highlight potential internal divisions that need to be managed. Ensuring a united front while allowing for diverse opinions within the party will be crucial.

4. Resource Constraints: As a smaller party competing against well-funded Dravidian majors, the VCK faces resource constraints in terms of campaign financing and organizational infrastructure.

5. Media Representation: Ensuring fair and adequate media representation, especially in a landscape dominated by channels sympathetic to larger parties, remains a challenge.

These challenges also present opportunities

1. Positioning as a Credible Partner: The VCK can establish itself as a credible partner with strength alongside the major Dravidian parties, appealing to voters seeking change while remaining rooted in its core principles. However, it also has the flexibility to navigate between the AIADMK and DMK, allowing it to adapt to the evolving political landscape.

2. Coalition Building: This strategy may lead the VCK to reconsider its alliance, switching from the DMK to the AIADMK, further diversifying its political partnerships, while advocating for coalition governance to build alliances with other smaller parties and emerging political forces, creating a more level-playing field.

3. Issue-Based Politics: Focusing on specific issues like the liquor ban and social-justice stand against Hindutva politics can help the party distinguish itself and attract issue-conscious voters.

4. Leveraging Social Media and Alternative Platforms: To overcome traditional media constraints, the VCK can leverage social media and alternative platforms to reach voters directly and shape political narratives.

5. Nurturing New Leadership: The emergence of leaders like Aadhav Arjuna presents an opportunity to groom a new generation of leaders who can broaden the party’s appeal while maintaining its core values.

The Dawn of a New Political Era

As we approach the 2026 Assembly Elections, Tamil Nadu stands at a political crossroads. The traditional duopoly of the DMK and AIADMK faces challenges from changing voter demographics, emerging political forces, and evolving social dynamics. In this context, the VCK’s rise represents more than just the growth of a single party; it symbolizes the potential for a more diverse, inclusive, and ideologically driven political landscape in the state.

The call for coalition governance, whether it materializes in 2026 or serves as a longer-term goal, signals a growing desire for a more representative and balanced political system. It challenges the established norms of Tamil Nadu politics and opens up possibilities for new forms of political engagement and governance.

The VCK, under Thirumavalavan’s leadership and with strategic inputs from figures like Aadhav Arjuna, appears poised to play a significant role in shaping this new political landscape. Whether this translates into Deputy Chief Minister post for Thirumavalavan or other forms of increased political influence remains to be seen. However, what is clear is that the era of unquestioned single-party dominance in Tamil Nadu may be coming to an end.

As the state navigates these political currents, several questions remain:

1. Will the major Dravidian parties adapt to the changing political realities, or will they resist the calls for more inclusive governance?

2. Can the VCK successfully broaden its appeal while maintaining its core ideological commitments?

3. How will new entrants like actor Vijay’s party impact the established political equations?

4. Will the push for coalition governance in Tamil Nadu create more stable and representative governments that can effectively address the complex challenges facing the state, including economic development, social justice, and inclusive growth?

The answers to these questions will unfold in the coming years, shaping not just the outcome of the 2026 elections but the long-term trajectory of Tamil Nadu’s political and social development. What is certain is that parties like the VCK, with their grassroots connections, ideological clarity, and strategic acumen, will play a crucial role in this evolving narrative.

As Tamil Nadu stands on the cusp of this potential political transformation, it offers a fascinating case study in the evolution of regional politics in India. The state’s ability to navigate these changes while addressing the aspirations of its diverse population will have implications not just for Tamil Nadu but for the broader discourse on federalism, social justice and democratic representation in India.

Summing up, the rise of parties like the VCK, the changing dynamics within the major Dravidian parties, and the evolving expectations of the electorate all point to a more complex, nuanced, and potentially more representative political future for the state. As this new chapter unfolds, it will undoubtedly offer rich insights into the ongoing evolution of India’s diverse and dynamic democracy.

Notes:

[1] The vote share of PWF was around 6.1 per cent; here we consider only the vote share of those PWF parties, who are currently allied with the DMK, of the PWF. Specifically, we exclude the vote share of late Vijayakant’s Desiya Murpokku Dravida Kazhagam (DMDK).

[2] Parali Puthur is a small hamlet in central Tamil Nadu that became significant in understanding the VCK’s internal dynamics and leadership issues. In 2012, it was often cited as an example of the VCK’s perceived failures. Initially, there were claims that the party had abandoned Dalits who had been attacked in the village. However, Gorringe’s research revealed that party activists and leaders had actually been the first to respond, offering support and pressuring police to file reports.

The villagers’ primary grievance was that Thirumavalavan himself had not visited the site. This highlighted two key issues:

- The longing for Thirumavalavan’s past activist role, where he would personally visit affected areas despite obstacles.

- The lack of well developed and recognized second-rung leaders within the party who could effectively represent the VCK in such situations.

What the example of Parali Puthur demonstrates is that the party remains heavily centralized around the unifying and exceptional figure of Thirumavalavan, and that second-rung leaders still lack grassroots acceptance and recognition. This centralization is illustrated what Artral Arasu said in a 2012 interview with Prof. Hugo Gorringe:

“I don’t know, it is impossible to become a popular secondary level leader. I have been with Thiruma for several years, I don’t know, but people only want Annan [Thirumavalavan]. At times I thought people didn’t respect me because I didn’t have enough power. It is the same with Sindhanai Selvan. Ravikumar is a thinker, writer, and he was a MLA, he was in power for some time, but it has been the same for him as well.”

This centralization and the challenges faced by second-rung leaders are further exemplified by an interaction Gorringe had with a party member named Tamizh Murasu:

“Seated on the front of the bike (a TVS 50) Tamizh Murasu kept up a stream of criticisms directed at Thirumavalavan and the VCK more generally. ‘Annan does not let secondary leaders like Sindhanai Selvan grow,’ he said, noting that this was the ‘same problem as Karunanidhi had with M. G. Ramachandran (MGR)…’. When asked why he remained in the party, he replied: “Look, just because my father is a drunkard, it does not mean that he is not my father anymore … Show me a better party and I’ll join it.’”

These accounts suggest that while there may be internal criticisms and challenges within the VCK, the party’s unity is not necessarily threatened by external influences or payoffs.

Forward Press also publishes books on Bahujan issues. Forward Press Books sheds light on the widespread problems as well as the finer aspects of Bahujan (Dalit, OBC, Adivasi, Nomadic, Pasmanda) society, culture, literature and politics. Contact us for a list of FP Books’ titles and to order. Mobile: +917827427311, Email: info@forwardmagazine.in)